Strategy and Tactics for Large Enclosed Structures - Part 4

In the effort to reduce stress while increasing safety, control and effectiveness on the fireground, every responding company must clearly understand their role during an enclosed structure incident. Based on hard lessons learned, when executing the enclosed structure Standard Operating Guideline, a worst case scenario approach must be used from the outset. To achieve this, all supply lines and hand lines must be charged and staffed ready for use before the first engine company enters to assess the structure (See Figure 1).

At minimum, three fully bunkered back-up engine companies, on charged handlines, and one truck company serving as a RIT, all equipped with thermal imaging cameras (TICs) and portable radios, should be standing by at the initial point of entry. These companies must be prepared to immediately back up or rescue the first engine company should conditions rapidly deteriorate. The second truck company coordinates forcible entry and ventilation with command, making certain to avoid ventilation that may cause a flashover or backdraft. All back up companies will be monitoring radio transmissions between the first engine company officer and command and will team up to assist the first engine company in attacking the fire from the same direction or to assist as needed.

Avoiding Life Threatening Hazards

Since disoriented firefighters suffered fatal injuries following exposure to life threatening hazards including collapses of roofs and floors, prolonged zero visibility, flashovers and backdrafts, all firefighters must anticipate and look for these hazards during the operation. A safety strong point associated with use of the enclosed structure standard operating guideline is that it is programmed for firefighters to consider and avoid these hazards during an incident.

For instance, a 360-degree walk around is initially conducted not only to look for fire and enclosed windows or doors for use as secondary means of access and egress but also for signs of a basement and to note whether the basement is involved. A fire in a basement should be considered a potential life threatening hazard to every firefighter on the scene. To prevent firefighters from accidentally falling through a fire weakened floor and into an involved basement, everyone must be immediately alerted.

Prior to conducting a cautious interior assessment, firefighters will also examine concealed ceiling spaces for the presence of lightweight wooden or steel truss construction or unprotected steel and for hidden fire which can cause a sudden collapse of the roof. Moreover, a cautious interior assessment is a risk management process used to determine if it is safe enough for firefighters to advance to the seat of the fire from the initial point of entry or if it would be safer to approach the fire from a different side of the structure, closer to the seat of the fire. When this approach is used safety is enhanced because exposure to dangerous prolonged zero visibility conditions are minimized, reducing the possibility of a firefighter running out of air before exiting the structure. Similarly, the use of a "short interior attack" may also improve the safety and effectiveness of the rapid intervention team because shorter travel distances may reduce the overall difficulty and time associated in reaching and removing a downed firefighter.

The Potential for Flashover & Backdraft

In addition to protecting the lives of citizens and extinguishing the fire, firefighters are trained and expected to protect personal property. One common way this is accomplished during heavy smoke conditions is to wait until fire is actually visible before opening the nozzle and discharging water. This serves to prevent water damage and overall property loss. However, in certain circumstances, this traditional practice contradicts the priority of ensuring firefighter safety. Should a concern to prevent water damage mean that a firefighter may not take the initiative to protect him or her self against a life threatening event such as a flashover? No, since firefighters are instructed not to take unnecessary risks to save a structure, it follows that they should not risk their lives to prevent water damage.

Therefore, for safety and survival, firefighters working on the interior of any structure, opened or enclosed, must recognize the signs of flashover and understand the action to take to prevent fatal exposure. Firefighters may see fire rollover at ceiling level in a room, which is actually the ignition of fire gases. Since "rollover" is a sign of imminent flashover, firefighters should either, fully open the nozzle to hit the fire to prevent a flashover or immediately exit the room. Flashover, which is the simultaneous ignition of all contents in a room and the cause of countless firefighter fatalities, may also occur in zero visibility conditions.

In simple terms, the signs include hot ambient temperature and heavy smoke conditions. When this "hot and heavy" combination of conditions is encountered and to prevent an engulfing flashover event, firefighters should not enter these spaces. But when firefighters are in this life threatening situation they should consider dropping flat onto the floor as they fully open and aim all nozzles to the ceiling where flashover first begins.

This survival tactic, although a last resort maneuver, was successfully used to prevent the fatality of firefighters in Washington D.C. This tactic must be clearly understood by all crew members in advance and used without hesitation when required. The overriding need to maintain safety and survival of firefighters in this specific situation justifies its' use.

Firefighters should also be aware that increasing heat may not be initially felt by fully bunkered firefighters at floor level in large enclosed structures with higher walls and because of heavy smoke conditions, rollover may not be visible without the use of a thermal imaging camera.

An explosive backdraft may occur if air is introduced into a concealed space in which a smoldering fire is producing smoke and gases which are hot enough to ignite yet require the introduction of air. Firefighters are familiar with the exterior signs of a backdraft. These include heavy smoke puffing from all openings of a structure or air being sucked or drawn back into the building.

One critical interior sign of an impending backdraft is the presence of a layer of light, moderate or heavy smoke or puffing smoke and lazy flames seen along the ceiling. When this condition is observed, officers should consider evacuating the structure and, if safe, calling for vertical ventilation. It is therefore important to initially delay implementing horizontal ventilation until the officer conducting the interior assessment and who is personally observing the smoke conditions makes a request through command.

Utilizing Multi-Layered Approach to Safety

In addition and prior to the execution of a cautious interior assessment at a structure having a suspended ceiling, the truck company serving as the RIT should raise a ground ladder to the top of the interior wall, next to the point of entry. The ladder should be used to pop ceiling tiles and to enable a firefighter to climb the ladder, use a TIC to scan the attic space for fire and to note and communicate the presence of trusses. This is highly recommended as collapses of roofs and ceilings leading to disorientation, entrapment and line-of-duty deaths have occurred when a check for fire in the ceiling space was initially overlooked.

All firefighters should be aware that the common firefighting task of "pulling ceilings" has initiated backdrafts when unsuspecting firefighters checked for fire extension in the ceiling space after advancing deep into the interior of enclosed structures. Avoiding this hazard in the future however, will be accomplished by informing firefighters of the hazard and completing this task at the point of entry which affords the safety of a near by exit and multiple handlines and a RIT to assist if needed. A multi-layered approach to achieving overall safety during the operation is also incorporated and consists of using:

- A calculating guideline which avoids risk and makes it easier to control and monitor the movement and accountability of firefighters in the structure

- Charged supply lines providing a continuous and adequate flow of water.

- Fully bunkered back-up companies equipped with TICs and holding charged handlines ready to immediately cover interior firefighters with protective streams and to provide rescue or assistance if needed.

- A TIC equipped rapid intervention team standing by at the point of entry and possessing greater awareness of the location of firefighters on the interior.

- A recognized risk management statement which defines acceptable risk

- The oversight provided by a safety officer and most importantly,

- The increased safety afforded by the firefighter's close proximity to points of entry which serve as safe points of egress if prompt evacuation is required.

In addition, the incident commander, safety officer or any company officer can order a withdrawal or emergency evacuation of firefighters from the structure at any time should fire break through the roof, an increase in the volume of smoke develop, signs of structural weakness becomes evident or for any other safety related reason.

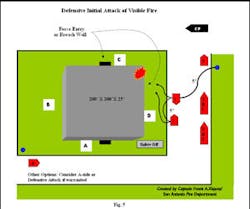

Defensive Initial Attack of Visible Fire

If on arrival or during the original 360-degree walk around, visible fire is located along the perimeter of the structure, companies should aggressively and defensively execute a straight stream attack on the fire where found while attempting to safely confine the fire to that portion of the structure (See Figure 5). Since pushing of fire by use of an exterior stream was never a factor in any of the large enclosed structure cases studied, it should not prevent firefighters from using a defensive attack to initially control visible fire while an effort is made to safely complete extinguishment.

This effort may require forcible entry to gain access through enclosed windows or doors close to the seat of the fire or breaching through the wall adjacent to the location of the fire. During the task to effectively cut off the extension of fire, and which is a task also conducted during a short interior attack, firefighters should anticipate and factor in the distance fire will spread when choosing a specific area of the wall to open.

Also, to avoid obstacles along interior walls, managers or employees should be contacted for advice as to the best location to make the breach. In addition and for added safety, truck officers should not hesitate to make large breaches capable of allowing the rapid evacuation of two fully bunkered firefighters, side by side, through the opening or openings made. In those cases when an attempt to breach a wall is determined to be unsafe or cannot be accomplished in a timely manner, command will be informed. Other tactical options command may consider if safe include attempting an interior A-side attack or a defensive attack if conditions warrant.

Flexible Guidelines are Key to Safe Operation

To help achieve the best possible outcome, it is important for the SOG to remain flexible. A prime example of this is found during the interior assessment. If determined that a "short interior attack" would be safer if made from a different side of the structure, all firefighters will leave apparatus and handlines at the original point of entry and will relocate to the other side of the structure. There, they will initiate a safe coordinated attack with back-up engine companies in position and with truck, RIT and safety officer support. Command will also reposition to observe and coordinate the effort at the secondary point of entry. Remember, there are no victims to rescue and therefore no reason to needlessly risk the lives of firefighters.

As a part of the guideline, this attack is made using handlines from another attack engine, previously staged on a nearby hydrant and anticipating the need to conduct a "short interior attack." As breaching or forcible entry is conducted, there are several ways departments across the country can accomplish the task of setting up and delivering effective flows from several handlines at the required side of the structure. As with any other emergency procedure, the safety and effectiveness of the guideline must be evaluated following each use and if required updated to ensure firefighters achieve the greatest level of safety and effectiveness possible.

Summary

Because of the inherent hazards of the job, firefighters understand that there is no guarantee of absolute safety on the fireground but they also realize the risk to firefighters must always be reduced whenever possible. In 100% of cases examined during the disorientation study, career and volunteer departments across the country initiated a fast and aggressive interior attack into enclosed structures resulting in 23 firefighter fatalities, serious injuries and narrow escapes. Numerous similar fatalities have occurred in the past and they continue in similar structures today.

As a result, firefighters can no longer blindly rush into enclosed structures to quickly locate and extinguish the fire. A different and safer approach must be used. In the future properly trained and equipped firefighters of progressive departments who respond to large enclosed structure fires will apply the hard lessons learned from the past. Firefighters will manage the incident by initially slowing the action down and by cautiously looking into the structure with a thermal imager to pin point the seat of the fire. A trained officer will then manage the risk by deciding if it is safest to attack the fire from the initial point of entry, from a different side of the structure, closer to the seat of the fire, or to simply surround and drown the fire.

Nationally, firefighter fatalities average 100 each and every year, indicating that current procedures are not as safe and effective as they could be. In response, departments must try a different way to ultimately break the trend, which may be as easy as modifying tactics to avoid the risk at enclosed structure fires. This is one common sense approach that can have a major impact in reducing property losses but more importantly, it may also help to prevent the line-of-duty death of firefighters.

Note: Information contained in the preceding articles implements the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation Life Safety Initiative 3 which calls for "Focusing greater attention on the integration of Risk Management with Incident management at all levels, including strategic, tactical and planning responsibilities."

Special thanks to: The National Fire Data Center; U.S. Fire Administration and The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Firefighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program

Related Articles

- Strategy and Tactics for Large Enclosed Structures - Part 1

- Strategy and Tactics for Large Enclosed Structures - Part 2

- Strategy and Tactics for Large Enclosed Structures - Part 3

- Enclosed Structure Disorientation

Related Links:

- Enclosed Structure Standard Operating Guideline (SOG)

- U.S. Fire Adminstration Firefighter Fatalities Homepage

- United States Firefighter Disorientation Study 1979-2001

William R. Mora has dedicated 32 years to the San Antonio, TX, Fire Department as a firefighter, engineer, paramedic and training officer. Captain Mora is currently assigned to the firefighting division. He serves on technical advisory boards for the University of Kentucky, Lexington and has studied educational methodology and hazardous materials in depth at the National Fire Academy.

Captain William Mora is a fire consultant with an interest in firefighter safety, strategy and tactics, standard operating guideline development and firefighter disorientation. Captain Mora has advanced new firefighting terminology, tactics and concepts to help firefighters recognize, manage and avoid the risk at structure fires. He has been published on the topic of firefighter disorientation and enclosed structure tactics in Firehouse.com, Fire Chief Magazine, and Fire Engineering Magazine, as well as in the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation Everyone Goes Home Newsletter. He has given presentations on the prevention of firefighter disorientation for the Fire Department Instructors' Conference, Texas Volunteer Fire Departments and for the Maryland State Firemen's Association.

The firefighter disorientation problem has compelled Captain Mora to provide assistance to fire officials, safety educators, grant writers, and fire industry professionals with valuable researched information. He has been active in the effort to prevent firefighter disorientation and traumatic structural firefighter fatalities. Working towards that goal, Captain Mora conducted an analysis of 444 structural firefighter fatalities, identifying a large percentage of line-of-duty deaths occurring at enclosed structure fires where offensive strategies were used. He served as a participant at the 2004 and 2007 National Fallen Firefighters Foundation Life Safety Summits and currently serves as an advocate for the Everyone Goes Home Firefighter Life Safety Initiatives Program for the state of Texas. Captain Mora is the author of the United States Firefighter Disorientation Study 1979-2001 which appears in the United States Fire Administration's annual report: Firefighter Fatalities in the U.S. in 2003, 2004 and 2005. You can contact William by e-mail at: [email protected].