Detached residential garage fires are common. When you hear that over the radio, odds are you’re going to a working fire, as it usually takes time to get going before anyone sees it – or a civilian in the garage either intentionally (uncommon) or unintentionally (common) was the cause of the fire.

History tells us that when we are dispatched to a garage fire, literally anything may be inside. Simply put, civilians fill their garages with whatever they don’t want in their homes, and more. Specifically, a residential garage fire can be like responding to a ticking bomb – and that is what the firefighters in Pennsville Township, NJ, found in February 2006.

Thanks to Chief Larry Zimmerman, Chief Jeff Hoffman, Deputy Chief Jerry Brown, Captain Cliff Boxer and Firefighter/EMT Chris Hagan for their help with this month’s close call. Additionally, thanks to the Pennsville Township Police for their assistance.

Pennsville Township is in southwestern New Jersey, adjacent to the Delaware River in Salem County. Pennsville is about 26 square miles and has a population of approximately 14,000. The Township is mostly suburban, but contains two chemical plants, a power plant, numerous strip malls and several interstate highways. The township is protected by two fire companies: Pennsville Fire & Rescue Company, led by Chief Larry Zimmerman and Deepwater Fire Company, led by Chief Jeff Hoffman. Both fire companies are also responsible for responding in the event of an emergency at a nearby nuclear power plant. Both fire companies run about 400 calls per year, a large portion of which is mutual aid, and have about 30 volunteer firefighters each.

This account is from Deputy Chief Jerry Brown, the incident commander:

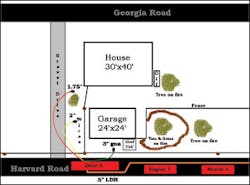

On Feb. 10, 2006, at 2:19 A.M., Pennsville Station 5, Deepwater Engine 7, Salem Engine 6, Pennsville EMS and Woodstown FAST 12 (a rapid intervention team) were dispatched to a reported working garage fire at 11 Georgia Road. Initially, there was confusion as to the location of the fire because the detached garage was directly behind 11 Georgia Road on Harvard Road. Pennsville EMS Ambulance 5-8 arrived first, as it is staffed 24 hours a day, and reported a well-involved structure fire with exposures. The stand-alone garage measured 24 by 24 feet and was set up as a motorcycle workshop. The garage was about 20 feet from the house and a light wind was blowing toward the house from the garage. Exposures included the house, numerous 25-pound propane tanks stored outside the garage, three 40-foot-tall pine trees and a heating oil tank next to the house.

As the first-arriving officer on Quint 5-6 (staffed with a crew of five), my primary concerns were establishing a water supply, protecting the exposure house and ensuring that no one was inside the house. The house was on the C side of the garage and was a serious concern, as the vinyl siding had already started to melt. I established Harvard Road Command and had my crew deploy the first handline to the house for exposure protection. As Rescue 5-9 (with a crew of three) and Engine 7-1 (staffed with five) arrived, I ordered them to place a second handline in service and search the house with a thermal imaging camera for fire extension and to ensure everyone was out.

At about this time, a large explosion occurred, mainly blowing out the B side of the garage, which was where the handline crews were operating. After the explosion, I checked with the other officers on scene to make sure that no one was hurt or missing. There were no injuries and everyone was accounted for. Engine 7-1 also deployed a three-inch line with a 500-gpm monitor on the A side for extinguishment of the garage. Engine 6-1 was initially used as a rapid intervention team until Woodstown arrived.

As with any incident, mistakes were made and we can learn from them. Do not assume that a residential garage fire can not have the same type and quantity of hazardous materials as a commercial garage. This garage had numerous cutting and welding equipment, compressed gas cylinders and a 100-pound propane tank, which was the source of the BLEVE (boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion). Fortunately, no civilians or firefighters were injured by the explosion.

Firefighters at the scene experienced a delay in getting their handline charged, which kept them back from the garage and the explosion. The first attack line got hung up in the crosslay, so the crew pulled a second attack line for the exposure house. (The department had recently changed nozzle types, to larger models.) Once the line was deployed, the can man called for the line to be charged, but the message was not received due to a dead battery in a portable radio. The firefighter had to walk over to the pump operator to tell him to charge the line.

After any type of explosion or fireground “emergency,†you should check all of your equipment, even the equipment that was left on the truck or engine. At a later fire, when we had to lay out more large-diameter hose (LDH) than we did at this fire, several sections of LDH had holes burned in them. This became readily apparent when the LDH was charged. The sections of hose that had holes burned through were still in the hosebed at the garage fire. Flaming debris had landed in the hosebed after the explosion, unknown to anyone.

This account is from Captain Cliff Boxer III, the Rescue 5-9 officer:

Walking up to the incident commander, I noticed arcing wires lying on the ground coming from a utility pole. I also heard an extremely loud venting noise coming from the garage. Three 40-foot-tall pine trees were well involved, and their canopies overhung the garage and the house. I have a new respect for our wildland firefighter brothers and sisters after seeing how a pine tree becomes a 40-foot-tall roman candle, let alone three of them!

A large explosion occurred while I was kneeling down putting on my airmask. The explosion was extremely loud, as friends of mine that lived several streets away later told me the explosion woke them out of bed. I felt a concussion and a blast of hot air go by me. Flaming debris from the explosion landed on the roof of the house and in the street. Initially, it was hard for me to believe that what had just happened actually happened and how fast it occurred. I started looking around at all of the firefighters to see if anyone was down or appeared injured. I went over to the firefighters who were on the first handline and were closest to the explosion. A section of wall made of four-by-eight-foot plywood had landed mere inches from where they were positioned, but they were not hurt.

Overall, this operation was a success because no one was injured and the exposure house received only minor damage. One critical lesson is that when any type of compressed gas cylinder is venting, it could explode at any minute; in this case, less than three minutes from when venting first started.

When the fire department first arrived, there were numerous bystanders watching the fire. Fire department personnel directed these people to leave, but they were later told to move their cars out of their driveway by the police. It is important to remember that not all responding agencies have the same priorities. It was not known by the fire department, until after the fire was out, that the police had asked the neighbors to move their cars. This placed one resident right next to the garage at the time of the explosion as he backed his car out of his driveway. Better communications with the police were needed to ensure that the fire department’s concerns were understood by everyone on the scene.

The wires down in front of the garage were another concern throughout the entire incident. The local electric company was called for by the police, as well as the fire department. A firefighter was posted to warn everyone about the wires and to stay away. After the fire was extinguished, the police started their investigation prior to the electric company arriving and de-energizing the wires. At this point, the wires were no longer arcing, which made them more dangerous. When wires arc, everyone sees the arcing and instinctively stays away. When they stop arcing, it becomes easier to forget the wires were there or that they were still energized. During their investigation, a police officer was seen walking directly through the wires. The police officer was warned that the wires were still live as he walked through them. Even trained professionals can get tunnel vision and lose focus on their surroundings. We must remember that just because the fire is out, the incident is still not over and that other agencies may need the protection and support of the fire department.

This account is from Firefighter/EMT Christopher Hagan, who was on initial attack handline:

I was riding in the can position, which is the fire attack riding position at Station 5 in Pennsville. We left Probationary Firefighter Jason Ross at the hydrant at the corner of the block. On arrival, we had a detached two-car garage on the officer side of Quint 5-6.

While deploying the first handline, the nozzle got stuck on the overhead ladder. We decided to abandon that line and pull another attack line. Firefighter Mike Toms and I stretched the line dry to about three feet from the doorway of the garage, then we called for water from Firefighter Phil Gagliardi, Quint 5-6’s chauffeur. Due to our radio dying, there was a delay in getting water. Right away, we realized we were not getting water and started to back away.

While backing away, there was a large explosion, followed by a collapse. There were pieces of debris everywhere and a four-by-eight-foot piece of plywood landed right next to my crew member and I. Right after that, we received the water in the line and started the fire attack on the C side of the garage to protect the house, which was starting to become an exposure problem. After that, there were multiple handlines in service and the fire was extinguished.

In all, safety concerns were probably being too close to begin with and getting seriously hurt or stuck in the collapse. Basically, when it comes down to it, a detached garage with no occupants trapped is not worthy of an overly aggressive attack.

These comments are based on Chief Goldfeder’s observations and communications with the writers and others regarding this close call:

Clearly, experience tells us that firefighters should expect the worst at a garage fire. A few observations:

Setting priorities. The first-arriving firefighters’ priorities as discussed above are right on – establishing their water supply, protecting the exposure and ensuring no one was inside the house. Additionally, as a part of that, the protection of the firefighters is critical. While it should be understood without saying, we must be reminded that firefighters must be fully geared, head to toe, with no exposed skin. Some firefighters may want to approach to do truck company work, but this is a clear case where charged hoselines are critical prior to approaching, for the protection of the members. That was done well in Pennsville that evening.

Ask the civilians. It is very difficult to pre-plan private property, such as in this case. While we should expect the worst, if civilian occupants are on the scene, ask them what’s inside. It couldn’t hurt.

The chief/incident commander in the front seat. While it is no longer the practice in Pennsville Township to have the chief/incident commander normally ride the front seat, it is of concern in other areas. Traditionally, in many volunteer fire departments, chiefs would respond to the firehouse and ride the apparatus, but that creates a problem: In what role is the chief functioning in? Incident commander? Company officer? Both? That is the problem.

The fire officer riding the front seat needs to supervise that company – and that can’t be done if he or she is also the incident commander for more than the first few moments while awaiting the battalion chief, deputy chief or whoever is responding to fill that role. The solution? A “duty officer†or “command car.†The officer who has that vehicle (assigned or rotated through several chiefs etc) responds from home or work with the intention of commanding the incident. The “separation†of the company officer role and the incident commander role is critical.

Stretching the initial attack lines. As has been said by some excellent chiefs for years, get water on the fire and that can often make your other problems go away. There was a problem stretching the first line off the quint – it got caught in the ladder and due to that there was a delay. While the timing may have worked out to their advantage, that was not intentional and the firefighters knew to back away. All departments upgrade equipment; in this case, they had recently changed nozzles. But whenever any equipment is moved, changed or upgraded, it has to be tested to insure it will work – every step of the way, including rapid deployment. In this case the larger nozzle caused a problem that might have been avoided if it had been pulled and deployed numerous times during training. A lesson for all of us.

Using monitors. I am a big fan of small, lightweight, 500-gpm ground monitors, as they let us deploy a large amount of water with minimal staffing – sadly, these days in career and volunteer fire departments, that can be a factor. They also let us place big water in tight areas. More and more, apparatus are equipped with at least one of these, pre-connected to a 200- or 300-foot three-inch line for some serious power. If the goal is to deliver big water quickly (and if it isn’t, you have been on too many EMS runs lately), this is often a great solution, as was done at this fire.

Communications. While the dead radio battery was a problem in this fire, it could have been a bigger problem if the firefighters had a different fire, crawled down a hall, into a basement and then tried to call for help. The solutions? Every riding position should have a radio on charger and additional radios should be available for other arriving firefighters. No firefighter should ever work without a radio. It provides backup in case one battery or radio dies as well as ensures communications for everyone.

Downed power lines. Several firefighters have been killed recently due to electrical wires being down. The Pennsville Township firefighters understood the hazards involved and took appropriate action to guard against a tragic outcome.

Cylinder venting. The sound of a cylinder venting can often be covered up, but if you think you hear it (a constant hissing sound), react immediately. Reaction means clear the area and tell command what you hear – and what you suspect. Few firefighters have regretted moving back and out of the area after hearing the hiss, followed by a tank explosion, BLEVE or otherwise.

Police on the scene. In almost all cases, the police arrive with us or, quite often, before us. While they are there to help, their role, responsibility and “place†at a fire scene must be made clear before an incident so it is clear to all. That’s called “interoperability.†Understand that you are dealing with police officers who are always used to being in charge, but they are not in charge of the fire operations. They can be a major help in their support role (and have an excellent relationship with the Pennsville Township firefighters), but they also must follow the rules of incident command and work within the fire command structure for their own safety – and the safety of civilians and the firefighters. In this case, well-intentioned police ordering civilians to take action contrary to the fire command could have ended up badly. By the local police understanding ‘the game plan†(how and why we do what we do) prior to the run, there is a greatly increased chance of everyone being happier at the end of that run.

As firefighters, we have been taught since Day 1 to expect the unexpected. Garage fires, and specifically private residential garage fires, can quickly affirm the need for us to heed that warning and be prepared organizationally as well as personally from a training and operational standpoint. While some lessons were learned in Pennsville Township, as there are in most any run any of us make, they clearly had many “systems†well in place to allow their members to return home safely after this run.

William Goldfeder, EFO, a Firehouse® contributing editor, is a 32-year veteran of the fire service. He is a deputy chief with the Loveland-Symmes Fire Department in Ohio, an ISO Class 2 and CAAS-accredited department. Goldfeder has been a chief officer since 1982, has served on numerous IAFC and NFPA committees, and is a past commissioner with the Commission on Fire Accreditation International. He is a graduate of the Executive Fire Officer Program at the National Fire Academy and is an active writer, speaker and instructor on fire service operational issues. Goldfeder and Gordon Graham host the free and noncommercial firefighter safety and survival website www.FirefighterCloseCalls.com. Goldfeder may be contacted at [email protected].