As mentioned in the past several columns, we normally don’t identify fire departments here, but several departments have told us that they are willing to openly share their stories. Again, that is a refreshing approach, as difficult as it can be. This month, we look at a near-tragic event involving the Blackstone, VA, Volunteer Fire Department. Our sincere appreciation goes out to Chief Walter “Mac” Osborne, the members of the Blackstone and neighboring fire departments, and especially photographers Billy Coleburn, Ed Conley, Pete Ellington and Rick Gunter for their cooperation in preparing this month’s column.

This account is provided by Chief Osborne:

Blackstone is a small all-volunteer fire department that serves the citizens of the Town of Blackstone (3,800 population) and surrounding Nottoway County. We provide fire, rescue and EMS first-responder services. We normally run about 200 fire calls and 300 EMS calls a year. Most of our runs consist of minor vehicle accidents and fires, automatic alarms, brushfires, and occasional house or mobile home fires. We average a larger fire about every five to seven years. We operate three engines, one heavy rescue, one tower ladder, one brush truck, one tanker, an EMS unit and other support units. Our staffing consists of 40 on-call volunteers. Our average response in manpower at a incident is 12 members plus mutual aid. We also have a “junior department” that has four firefighters and a ladies’ auxiliary that supports our operations.

Our department had never had an aerial truck, but as fire chief I supported the effort to have one available in our community. In April 2003, we found a used Mack 75-foot Aerialscope for sale. At the time, our town leaders did not agree that we needed an aerial truck and would not fund its purchase. The nearest mutual-aid aerial truck is almost 30 miles away, so we thought it was good insurance to have a “truck” available when needed. Our department members took some funds we had left over from our fire station building account, purchased the truck and presented the title to the town. Other than the extensive training, we never had the need or the opportunity to have it “up” at any of the few structure fires we had run – until March 11, 2004.

That day, we were dispatched to a reported fire in the alley behind Mitchell’s Restaurant at 103 S. Main St. This building is in the downtown historic district, built as a store in the early 1900s. All of downtown was part of a revitalization effort about 20 years ago, when many storefronts were restored, trees planted and period lighting installed. The store, last known as Rose’s, was vacant until Gus Mitchell purchased it and renovated it into a restaurant in the late 1980s. He had a very good business and it was known to be the place business leaders and local politicians regularly met and ate.

The restaurant retained the building’s decorative metal ceiling in the dining room. In the middle there was a kitchen and a small banquet room, while the rear was used for receiving and storage. The old Rose’s office area that once overlooked the sales floor was redone as an office. Over the years, his business expanded to catering parties and special events.

The building contained one single room, below grade (at the C-D corner) that once served as a boiler room. This room had been converted to a shop to support repairs and maintenance for the restaurant operations. The all-wood, unprotected stairway from the ground floor passed over this room to a landing, then up the stairs to a single room used for storage and as a makeshift equipment room. It is believed that this room had a number of wall and ceiling coverings, including open wood rafters on the back two-thirds and old wood shelving on the B wall that was about 50 feet long, used for stock when it was Rose’s. It had a combination of plaster on brick, tongue-and-grooved wood on the walls. The front one-third (under an old A roof) had decorative metal ceiling tiles.

It was felt that the B wall had a good chance to survive a fire, as did the B-side exposure because of its later construction. The D side, however, had a wooden wall that protruded out where an old stairway from the front street level was located. At one time, over 40 years ago, these steps would have led to the upstairs to both structures; however, it is our understanding that it appeared to have been changed (possibly when Rose’s moved in) and this wooden wall section was built to divide the buildings.

Two metal fire doors had been provided for the second story of the exposure at the top right of the stairs. This led to an old storage area over the building next door. Years ago, this building had been a hardware store, later a department store, a couple of discount stores and finally the downstairs was converted to a gym. Approximately 20 feet of the A-B-C wall of the first floor had been divided to form a banquet room for the restaurant and a gift shop in the front. The fire wall between them was breached on the first floor to form a walkway with no door. However, the owner was allowed to add drywall on the ceiling and walls to meet local building codes.

The upstairs was not being used at the time; the rooms on the left had a plaster/lath construction while the large rooms on the right had open joists to the roof. Holes were breached between the two areas over the gym, presumably in the 1940s to 1960s. The upstairs right contained old store fixtures and a couple of empty smaller rooms, most not used since the 1940s or 1950s.

The left rear corner was an old kitchen that had been converted to house the separate heating and cooling system for the gift shop and banquet room below. Sometime in the past, both fire doors had been left open and were open at the time of the fire. This building had a five- to-eight-foot-high attic in the front that continued down the back to about six inches. The only attic that Mitchell’s appeared to have was under the A roof in the front, above the metal ceiling. The upper story of the gym front wall was decorative sheet metal (made to resemble a cast-iron building) over a wooden framing/wall (exterior) with bare and plaster lath inside. Mitchell’s measured 8,500 square feet on two floors and the gym took up about 14,500 square feet, also on two floors.

- Building construction. A 100-year-old building of balloon construction with brick walls and a sheet metal-covered wood/brick front wall. Two-thirds of the roof is sloped to the rear and the front one-third is an “A” with built-up material roofing. The first-floor front is all glass with decorative tin on the second floor.

All three are of brick-walled construction with timber joist/rafters and void spaces. The gym was two buildings many years ago, but now is one building due to wall breaches on the first and second floors. The downstairs wall has been opened in three large areas and upstairs in two smaller openings to join buildings together.

- Utilities exposure. The main electrical feed for all Main Street buildings, cable TV system main trunk line, local telephone neighborhood main service cable, long distance switching for town/county, fiber optic phone switching equipment located three blocks south (including cellular to ground) were in the alley behind the buildings.

Initial Call and Incident

The building’s owner and restaurant operator were making repairs to a catering trailer parked in the alley with a small welder. The welder was connected to a long extension cord run though the rear door, back into the building, and connected to a 120-volt outlet near a workbench. The workbench was in a converted furnace room under an unprotected wooden stairway leading to the office located a half-story above the main floor and the second floor used for storage and some mechanical equipment.

The owner’s young son saw fire coming from the “shop” (the old furnace room) and alerted his parents. His mother called in the fire, but the fast-moving fire destroyed the telephone wires before she could give the dispatcher all the information. All that was heard was that there was a fire in the alley behind Mitchell’s Restaurant. The building was evacuated by its occupants, including over two dozen Mecklenburg County/Charlotte, NC, SWAT team members and their EMTs (they were training at Fort Pickett that day and were at Mitchell’s for dinner, and they would play a supporting role later). Everyone was out when the fire department arrived.

As we had discussed at our monthly officers’ meeting a few days earlier, a fire in this building would be a major event and could threaten our entire downtown business district. It is one of those areas where you dread a fire.

I arrived about 10 minutes into the incident after stopping at the fire station to pick up the command unit and make a mutual aid radio call to the Brunswick County Dispatch Center to request an aerial from South Hill, VA.

Timeline

4:40 P.M. – Time of call.4:41 – Fire department is dispatched. First alarm: Blackstone Volunteer Fire Department Engines 4 and 3, Truck 9 (a 75-foot aerial), Rescue 10, Command Unit 2; Fort Pickett Engine 12 responds on automatic mutual aid.

4:44 – First-arriving police unit reports “fire in the building.”

4:46 – The first-arriving fire officer, Lieutenant Tony Bradford (in a personal vehicle), reports a “major commercial fire.” He establishes command, advises that the fire is in the building and has extended to the second floor. Heavy fire is also reported at the rear. Command requests the Crewe Volunteer Fire Department for mutual aid. Blackstone Engine 4 arrives on the scene. A 1¾-inch line is pulled and advanced to the front door. Downstairs has light smoke.

4:47 – The fire chief is responding. He requests mutual aid from the Kenbridge Volunteer Fire Department and verifies that Crewe is being dispatched. He requests a second alarm for Blackstone.

4:48 – The Nottoway County Emergency Squad (EMS) is dispatched on automatic mutual aid. Truck 9 is on scene at the front of the building. The Blackstone second alarm is sounded.

4:51 – The fire chief contacts Mecklenburg County for the South Hill Volunteer Fire Department’s 75-foot aerial (the next-closest aerial) and a support pumper.

4:53 – The fire chief arrives on scene, holds a quick face-to-face meeting with Bradford and assumes command. Bradford becomes “operations.”

4:55 – Fort Pickett requests an assignment, lays a five-inch supply line from a location one block east to the rear of the structure.

5:05 P.M. – The Kenbridge Volunteer Fire Department arrives on location, lays a line and is assigned to the right exposure, Johnny’s Gym.

5:06 – The Crewe Volunteer Fire Department arrives and is sent to the right rear of fire structure to assist Engine 3’s attack.

5:14 – Command calls the Blackstone dispatch center, reports an explosion on the scene and asks for “every ambulance in the county.”

5:15 – Command calls the Nottoway County Dispatch Center on the same frequency and reports an explosion and building collapse. Requests all available volunteer rescue squad ambulances for multiple firefighter injuries.

5:28 –South Hill Ladder 7 and support on location.

5:29 – Nottoway Ambulance 725 enroute to Farmville Hospital with one firefighter. Nottoway Ambulance 720 enroute to Petersburg Hospital with two firefighters.

6:01 P.M. – Some EMS disregarded by command as incident becomes under control.

6:02 – Ambulances 724 and 725 returns. All firefighters are “treated and released.”

10 P.M. – Some fire mutual aid returned to service.

11:15 P.M. – Command terminated. Engine 4 remains on re watch; all other units return to service.

Operations and Fire Attack

This was an “it’s way ahead of us fire” on arrival. The time of day, like on any incident, affected our response, since many firefighters were still at work and manpower is short for what we are facing. Automatic mutual aid and second-alarm mutual aid was coming, but it would take 10 to 15 minutes for the first wave to arrive. Main Street is literally our town’s main street, so it was clogged with traffic and parked cars. Some people were trying to move their cars and get out of the way while others emptied out of businesses, eager to get a look at the “excitement.” Police were doing a good job of shutting down the street and keeping people away, but a lot of people were still in the area. A police line was established early, and many local business professionals, politicians and other citizens stayed behind the line watching.

The first-arriving fire unit, Engine 4, with Sergeant Sam Nunnelly and Firefighters Timmy Barnes, James Major and Todd Pridgen, took a single 1¾-inch line through the front door. The front dining area had a light smoke condition. They went through the dining area and kitchen and found heavy fire in a storage/office area about 10 feet from the back door. The hose stream was not affecting the fire, which had spread up the stairs and already burned through the office area. By now, the second floor was heavily involved.

Conditions were rapidly going downhill inside, with ceiling-mounted heating equipment crashing to the floor and exposed aerosol cans on upper shelves exploding around the interior attack crew. They radioed command that they were backing out. They repositioned and continued to flow water as conditions worsened. As they backed out, the attack line became entangled in a maze of chairs and tables in the dining room and was left in place as they followed it out of the front door to safety.

We were fortunate to have two Crewe Volunteer Fire Department officers in the area when the alarm sounded. They both arrived at about the same time as our first Blackstone units. One assisted in the operations of our Engine 4 (now supplying the 1¾-inch attack line and Truck 9) while the other led a team from Engine 3 that was taking up a position at the rear of the gym, freeing up a few more firefighters for the fire attack now underway.

At the same time, Truck 9’s crew was removing the windows on the second floor for ventilation, clearing the fiberglass insulation in place behind them and flowing the truck’s turret gun through the front upper windows – first at 250 gpm, then later removing their stack tips and flowing 700 gpm due to an error in laying dual 2½-inch lines instead of three-inch lines. This was our first significant mistake: not setting the truck up for maximum flow, since it can deliver 1,000 gpm.

I arrived on the scene in the middle of the above operations. Heavy black smoke was banking down and visibility was zero for blocks downwind. Town Manager Larry Palmore told me that he was going to take down the main power grid for this and the adjoining blocks. I told him it was pretty grim for the restaurant, that the exposure on the left for now is on its own, and that we were going to concentrate on the restaurant and right exposure. (Larry was once a volunteer firefighter in Kenbridge, has been our town manger for some years and knows “how we operate.”)

Our town operates its own power grid, supplying most residents and businesses. Having quick responses from the Public Works Electrical Department has, for years, been a great advantage to us for many reasons. Sharing our radio band, they regularly monitor our dispatch channel and are usually on the scene in a short time without having to be called. Over the past 25 years, when the chips were down, an electrical bucket truck has been pressed into service on the fireground about a half-dozen times. Each time, it was noted that we would “never do that again” because of the clear loading and safety concerns of operating a 1¾-inch hoseline from a vehicle not designed for firefighting.

I assumed command as I arrived on the scene. The lieutenant who had command, a mutual aid chief and I communicated that we would “burn down the short side of the block” if we had, but we must protect the gym due to the common walls and attic spaces without fire walls farther south – but overall, we would be careful. We had discussed this block and others throughout the years and how we would do it, by concentrating on water supply, covering exposures, and watching for “textbook” signs of fire progression and spread.

I gave a junior fire department officer who was just arriving the job of accountability. Past Fire Lieutenant David Ostrander arrived at the command post and I designated him as the chief’s aide and communications officer. I walked from the command post about 70 feet south to get a good look again at the scene as a part of my ongoing size-up.

The fire was still growing in intensity. No fire was showing from the front of the building, but a large amount was venting from the rear, while black-yellow smoke continued to “puff” out of the front windows.

Incoming mutual aid from the Crewe Volunteer Fire Department was assigned to assist Blackstone Engine 3’s crew in the alley. These crews took a beating and were unable to make any head way. The narrow alley, barred windows and deep-seated fire were all working against them, but they were able to protect the JCPenney exposure in the rear. The heat and fire were slowly destroying the main trunk line, telephone cables and electrical lines in the alley overhead.

Assistant Chief Ray Armes, who was in the bucket of Truck 9, decided to change attack strategies due to the increasing fire. He placed Nunnelly in the basket along with Firefighters Robert Paulette and J.J. Jones to open up the roof of the exposure to the right to see why it appeared that the fire was starting to spread. Smoke was now starting to “lightly show” in the upper floor of the gym at the roof line, near where it connected to Mitchell’s. Armes ordered an additional pumper for a 1¾-inch line to advance up a stairway to the second floor between the buildings. The crew brought a 2½-inch line, but Armes asked them to take it back and get the other line. We were hoping the fire would vent itself through the built-up roof and that it would not spread, but it looked like the common wall was not going to hold. We were waiting for mutual aid to help with the exposures as additional Blackstone firefighters arrived.

The Kenbridge Volunteer Fire Department, under command of Chief Richard Harris, was given the assignment to enter and prevent the spread of the fire in the right exposure. They caught a hydrant one block south and laid in a single three-inch line, while their attack crew laddered the right exposure and removed a single second-floor window. A three-man crew (one from Blackstone and two from Kenbridge) took a 1¾-inch line to the second floor to search for possible fire spread to that building. Jones and Paulette were on the roof and just finished cutting a small “starter hole” in the standing seam metal roof on the right exposure and prepared to remove the cut section, while Nunnelly staffed the bucket and continued to flow water toward the rear of the building, while maintaining a safe egress via the bucket.

There still was no fire showing from the front, but for a time we were not applying water to the front (the aerial was tied up doing ventilation and related truck work). Armes briefly removed his helmet to don his facepiece as his crew prepared to enter. I looked back to my right to see a town electrical truck now sporting a 1¾-inch handline. The Kenbridge chief and town employees had it in a defensive mode in case the fire spread south, but otherwise were “lobbing” a small stream onto the roof of the gym. I briefly considered having it shut down (now that I have a “real” aerial device), but I was distracted by the urgent fire spread issue.

Acting as the incident commander and still directing overall operations, I was standing across the street directly in line with the door to the gift shop giving initial arrival directions to the South Hill fire chief on the radio. Suddenly, there was a burst of fire and heat from the right upper windows of Mitchell’s; less than a second later, a “smoke explosion” occurred in the upper floor/attic of the gym, going from right to left.

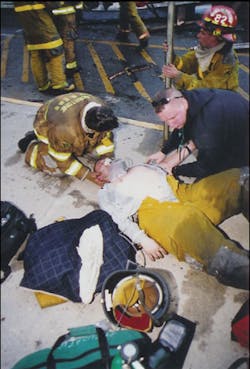

The rear second-story brick wall failed and fell outward, and plywood sheeting that had been nailed over the back windows was thrown about 50 feet into the alley. The crew operating at the C-D corner took cover and ducked as pieces of glass and plywood flew past. I turned and covered myself against the doorway of the insurance office. I could feel glass and other small debris showering me. The dozen or so firefighters operating on Main Street, in front of me, were pushed across the street by the blast. Armes’ crew, including Major, Pridgen and Firefighters Buzz Bryant and Ben Prosise, were struck by debris, with some ending up on the opposite side of Main Street close to me. Armes’ father, Firefighter Phillip Armes, was briefly knocked from his position at the pedestal turntable controls of Truck 9. The firefighters venting the exposure rode the roof up and down like a trampoline, then evacuated to the aerial bucket and were unharmed.

As I turned back, I saw that the second-story front wall of half of the gym was totally gone. I also saw firefighters kneeling on the second floor of that section, looking out at the street. They grabbed a ladder that was still in place and did a ladder bail/slide to safety, the last one making his way down carefully. All around me, I saw firefighters everywhere, on the ground, getting up or standing, sitting, lying in the street, some stunned. Many were holding their heads or were shaken up.

I keyed my portable radio and said, “601 to Blackstone. Send me every ambulance in the county.” The dispatcher replied, “10-4,” and I keyed up again and told her,” I have had an explosion and need every ambulance in the county now!”

I heard Assistant Chief Armes, and then saw him to my right. He and others were blown across the street by the blast. He was holding his head, screaming, “Get Sam, he’s on the roof!” I turned back and saw the aerial bucket swing clear of the roof, with firefighters in it. I yelled to the firefighter who was on the joystick, “Get Sam, he’s on the roof.” It took me a couple of times telling him that to realize that it was Sam and that he and his crew were OK.

He and I noticed lots of people in blue attending to the downed firefighters and I signaled him to get back on the fire. One of the “blue guys” ran up to me and identified himself as a Mecklenburg/Charlotte SWAT team member and EMT. He asked if the team could help. My reply was, “Yes, take the ball and run with it and work with our EMS branch.”(I wanted the volunteer squad to take care of EMS and my firefighters while the fire department units regrouped on the fire attack.)

These people, working with my local volunteer squad, triaged all of our members needing treatment quickly, helped package any who were to be transported by squads, and then helped with crowd control and evacuation of other businesses in the block. (After the blast, the attorneys and insurance company on the block were expecting the entire block to go, so many businesses closed and removed records and items. This secondary evacuation was underway with police assistance.)

In less than a minute, the ladder tower was back flowing water near the fire door area. It swept the attic of the gym, then the upper and lower floors of the restaurant. The incident caused a large roof collapse in the rear and the fire was venting heavily at the rear, relieving us of an immediate fire exposure to the front. The three-man crew that had been operating on the second floor of the gym later reported it being smoky and warm with limited visibility – then suddenly the room was filled with bright sunlight as the wall behind them was blown into Main Street (and onto the crews mentioned above) along with their handline. Firefighter Robert Abernathy, who was footing the ladder, believes that it cleared him and he was not injured.

At this point, I realized that the accountability tags had not been gathered from all incoming firefighters and mutual aid companies. I called the rear sector and asked them whether they were OK and to double check on all crews operating at the rear, then to get back to me with a damage report. I ordered everyone around me to “check on and find your buddy!” Several of us took a couple quick laps around the fireground in front of the building as we are searching for anyone that might have been trapped or injured. Remarkably, no one appears to have been pinned or trapped.

I met the Kenbridge fire chief face to face. He was wearing a suit (he is the mayor and funeral home director for his town) and his white shirt was stained with blood from a small cut on his neck. He told me that all of his people were OK, including himself . Later, he realized that his truck received heavy damage ($30,000) and that yet another close call had occurred when the operator of his top-mount pump panel engine went into the cab to retrieve his glasses at the time of the blast. The cab top was bent and the air horns and bar lights were destroyed, but he was protected by being inside for those few seconds. If he had been at the pump panel, the results could have been tragic.

A few of our firefighters found family members and were in “family hug modes” as I made another lap to check on the half-dozen or so who appeared to be hurt the worst. All were talking, some were mad, but I felt that most of them would be OK if I let the EMTs work on them. I got back in the saddle and tried to get us back to the fire, and also was making sure the building did not surprise us again. It was only now that I saw that the town’s light truck was still flowing a 1¾-inch line supplied by the Kenbridge truck, sweeping the attic of the gym.

A safety zone was established near the building with extra caution being given to keeping an eye on the few pieces of facade that remained. We agreed that a backdraft or flashover had occurred, changing our entire operation in an instant. I climbed up and did a face-to-face with Firefighter Philip Armes, who had been the pedestal operator of Truck 9. His son, Assistant Chief Armes, was one of the firefighters who appeared to need hospital care and I wanted to update him on his son’s condition. I noticed that both Truck 9 and Kenbridge’s truck were coated with a black, tar-like soot that must have come from the explosion. (Later, in reviewing the tape of our main dispatch channel, I could hear different incoming and EMS units calling command at this time, but I was tied up in looking, watching and talking on our fireground channel, so for a brief time command was not answering and was “missing.”)

The crews in the rear reported building damage, but no one injured, and they continued to encounter and attack the heavy fire in the rear, while it looked like the aerial was making good headway out front while we regrouped. The available remaining fire officers met out front to discuss the operation, as well as safety concerns and tactics from this point forward. I appointed one of my officers as a safety officer as the remaining firefighters worked to recover the remaining handlines that had been in place at the time of the explosion.

We regrouped and once again made a fire attack. Bradford led a crew that made a secondary search of the gym for remaining firefighters while assessing building stability and condition. The South Hill Volunteer Fire Department truck arrived and searched for a place to set up operations at the rear (the C/D corner of the gym and its exposure). Instead, it ended up on East Broad, where the aerial will reach the rear B/C corner of Mitchell’s and covered fire attack and exposure protection of that area. (Fire hose and utilities prevented an ideal setup.) EMS was still treating patients and started to transport the three who had to go to the hospital: Armes, Bryant and Major. They were sent to both Farmville and Petersburg, the two nearest hospitals in opposite directions. Later, all three were treated and released from the hospitals and made contact by cell phone with fire department members or family members on the way home.

I asked for and received a plastic tote of fully charged spare radios that had been recently donated to our department by a larger city that upgraded to 800 MHz. These radios were going to be placed into service later that week and were charged and ready for use in my personal vehicle in the lot at the station. They were passed out to mutual aid and supporting groups throughout the rest of the night’s operations, helping with firefighter safety and coordination of mutual aid resources.

It started to feel like I had things “going again” as we continued to hear incoming companies calling enroute to the dispatch centers and me. It appeared that I had only three injuries that will need medical help, but still I had experienced a violent incident and my mind was trying to cover all the bases, passing the final decision to the EMS providers operating around me.

Bad news travels fast, and at least three more agencies were still responding to us when they heard of our calls for help. Many departments work close in southside Virginia, even though many of us are located far apart. Over the years, through our firefighter associations, mutual aids calls, joint training and working together, we have formed friendships and bonds that showed that night as help poured in from all over the area. For some reason, long distance calls were not getting through to our dispatch center, so help was being sent “just in case it’s bad.” Mutual aid continued to stream in, as fire and rescue companies from all over southside Virginia responded. Soon, staging areas were full of fire and EMS units waiting for assignments. Victoria Fire and Rescue was assigned to cover our station and any calls, and later helped place our units back in service as they returned to quarters.

As I watched the incident become more stable, I realized by listening to radio traffic that something was happening to the area telephone system. We were getting more and more radio traffic about mutual aid requests and people being unable to contact us. As fireground cell phone traffic became less dependable, it dawned on me that over 40 or more years ago, when I was just a kid, our long distance service to town was taken out for a few days by a large fire that exposed the telephone cables in the same alley a block northeast of my location. The rear sector confirmed my thoughts that the cables in the alley were badly damaged. I radioed dispatch to contact Sprint and tell them that I was sure I knew what was wrong and it was at my location. At that time, we were down to “carrier-to-carrier” cell phone service with most local and long distance land lines down on our side of the county due to the damage.

Over and over, I realized how close we came to disaster. This was a huge close call to:

- The crew on the roof and in the bucket.

- The crews operating in the street out front struck by the collapsing building walls.

- The operators/engineers of the aerial and the Kenbridge engine missed by the same walls.

- The crew in the alley and the interior attack crew.

All should have been seriously injured or killed, but only three were transported and then released after short checkups.

The town manager, county building inspector and I met and I give them a tour of the remaining structure. Because the incident was located on Main Street and due to the extent of the damage, it was decided that the gym and the restaurant should be demolished as soon as possible to avoid any chance of the public being injured. The business owners and their employees worked through the morning to salvage what they could before the building was leveled later that day.

After the fire, there was a big concern about fire safety and the enforcement of fire codes; however, so far our requests for our county to provide and enforce national fire codes (other than new construction) have fallen on deaf ears. We do plan to continue this fight. To me, my local government is using the fire department as “last-resort” responders and does not realize the importance and risk involved in not adopting and enforcing codes countywide.

Our lessons learned:

- As a volunteer department in a small community, we are constantly in a battle for money and manpower, and all that relates to “risk management” at any given time. Because of this, things like pre-planning every building and fire prevention do not get done on a regular basis. Sometimes, we are too busy covering calls, raising money and training to do everything to run a “perfect organization.” It is to easy to get sidetracked with the political part of running a fire department while other projects sit undone or unfinished.

We did not have an “official” rapid intervention team hoseline in place during either entry. A lack of manpower prevented this, and I feel that both crews felt they could do the attack without the fear of being trapped or injured, but this incident shows that you are truly never safe from the unexpected on the fireground.

Too often, we hear of firefighters being hurt or killed in buildings with no life hazard, but we forget that sometimes the emotions of an entire community are involved when the “Main Street” that we all grew up with is in danger of being destroyed. Firefighting is dangerous work, no matter what you do, and you need to always expect the unexpected and always learn from each and every incident and apply that to the next – which we have!

These comments are based on Chief Goldfeder’s observations and communication with the writer and others regarding this incident:

The “Main Street” fire – one we all dread. Not only are we under pressure to preserve the downtown of the community, but if you are “lucky,” local officials show up to “supervise” and offer their sometimes welcome/sometimes not support and advice. In this case, a positive relationship with the town manager (a former firefighter) was of value.

Due to the length of this month’s incident recap, with all of its excellent details, we will be brief with our observations. But as brief as we may be, firefighters and command officers reading this have many lessons learned or reinforced with this fire:

Plenty of help on the first alarm. As shown above, the chief put several mutual aid fire departments on the road, in addition to the automatic mutual aid, on the first alarm. So often, we are asked the question: How much help do we need on the first alarm? An easily answered question. Fire departments must pre-plan their buildings and as a part of that pre-planning, the “what’s needed” question is asked. Factors such as needed fire flow (based on height, size, construction, load and internal protection) help determine that. With that as your base, the tasks that apply to the building must be applied such as water on the fire (sizes of handlines, master streams, etc.), water supply, access, search, rescue (the type of occupancy must be included as a part of your pre-plan), venting and related tactical objectives.

So many fire departments send “the same” first-alarm assignment to a house fire as a commercial fire as a strip mall fire as a school fire – and they are not the same! Different buildings and occupancies must receive applicable responses on the first alarm. We have two choices: to arrive at a building fire with a pre-planned first-alarm assignment based on the above factors, or not. Which would you rather do?

Large-stream handlines. Sometimes, a 1¾-inch line simply is not enough. It’s all based on the fire size, what’s burning and the line’s flow capabilities. A rule of thumb that some use is essentially a residential fire gets a 1¾-inch line and everything else gets a 2½. Of course, issues such as deployment and maneuverability are factors in line size, but so is the ability to flow water! How can that be dealt with? By training, drills, (hands on!), planning and plenty of firefighters (based on what is needed as discussed above) on the first alarm. Naturally, keep in mind portable master streams (some great lightweight devices are available) as well as deck guns and aerial devices.

Accountability. Clearly, this not an easy task, but if it is practiced on every run, with strict discipline, it will flow more easily on the working fires. The best accountability “system” is a tough company officer who will not allow members to be unaccounted for – and that is best accomplished by members staying together and no one operating alone. As well intentioned as junior firefighters may be, they do not have the authority, experience or expertise to manage accountability. If they are the first string of help, so be it, but as additional staffing arrives, that critical task must be managed by an appropriate firefighter, preferably an officer.

Firefighter rescue teams. Until companies return to quarters, things can go wrong. A well-staffed, well-equipped and trained firefighter rescue team must be in place – and may be in several places, based on a determination of needs.

Command support. The incident commander cannot function alone, although in some cases, as shown above, there is little choice until extra help arrives. As soon as possible, the incident commander must have several aides to support the operation. Radio operations, monitoring, scribes, contacts, phone calls and related tasks can divert the incident commander from focusing on the big picture.

The incident command system. We really have no choice but to operate on every run using the incident command system from the moment we arrive. Some may say it is a waste, but even if it isn’t needed on a small-scale run, what are we “wasting”? The incident command system doesn’t “cost” us anything, so let’s practice by using it on every run so that when the “big one” occurs, or when something goes wrong on the small ones, everyone is familiar with the system.

This close call on Main Street USA is a classic event that so many of us think about. As Chief Osborne wrote, there is much emotion when you are charged with “saving Main Street.” On the other hand, due to construction, access, water supply, staffing and other tactical considerations, a careful balance between the emotions of “saving Main Street” and the clear desire of all of us to have every firefighter return home after every call must be maintained.

Goldfeder Named to NFFF BoardThe Board of Directors of the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation (NFFF) has selected William Goldfeder, EFO, to serve on the board. Goldfeder, a Firehouse® contributing editor, is a nationally known speaker and advocate for fire service safety. He will serve on the 12-member board that provides oversight and direction to the NFFF’s many programs.

Goldfeder, a firefighter since 1973 and a chief officer since 1982, was promoted last month to deputy chief of the Loveland-Symmes Fire Department in Ohio. He has also served as a chief in Ohio, Virginia and Florida. Additionally, he is the recipient of over 30 operational and administrative awards and recognitions and received the Loveland-Symmes Fire Department Departmental Award of Excellence in 2003. Goldfeder recently completed his sixth year as a member of the Commission of Fire Accreditation International and has served on several National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) committees. He is currently a member of the IAFC Health and Safety Committee and an IAFC representative on the National Firefighter Near-Miss Reporting Task Force.

“Chief Goldfeder is a nationally recognized expert in the field of firefighter health and safety,” said Hal Bruno, chairman of the NFFF and a Firehouse® contributing editor. “He has become a leader in the campaign to reduce line-of-duty deaths, which has become a major initiative for the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation. We are fortunate to have him join the Board of Directors.”

For more information, contact the NFFF at 301- 447-1365 or by e-mail at [email protected]. Visit www.firehero.org to learn more about foundation programs.

William Goldfeder, EFO, a Firehouse® contributing editor, is a 31-year veteran of the fire service. He is a deputy chief with the Loveland-Symmes Fire Department in Ohio, an ISO Class 2 and CAAS-accredited department. Goldfeder has been a chief officer since 1982 and has served on numerous IAFC and NFPA committees, and is a past commissioner with the Commission on Fire Accreditation International. He is a graduate of the Executive Fire Officer Program at the National Fire Academy and is an active writer, speaker and instructor on fire service operational issues. Goldfeder and Gordon Graham host the free and noncommercial firefighter safety & survival website www.FirefighterCloseCalls.com. Goldfeder may be contacted at [email protected].