The line-of-duty loss of a firefighter changes the fire department in ways only understood by other departments that have suffered the same loss. Deputy Chief Mark Davis of the Charleston, SC, Fire Department observed the following in the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation video Charleston 9: The Ultimate Sacrifice: “We [the Charleston Fire Department] are part of a very sad fraternity of departments that have had numerous line-of-duty deaths and multiple line-of-duty deaths. As sad as that may be, our lineage will be, ‘How do you bounce back from that, admit what you did was not the appropriate thing, and then correct your fire department and set it on a path to be one of the best fire departments in the country?’”

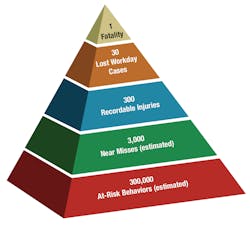

These words resonate with fire departments that make up Chief Davis’s sad fraternity. But what about fire departments that have (to date) been spared the tragedy and residual effects of an LODD? Avoiding a membership card in the “sad fraternity” should be every department member’s mission and objective. Even those holding a fatalist view (i.e., “It’s a dangerous job and bound to happen sooner or later”) do not have license to passively accept what they see as the inevitable. More likely than not, by a factor of 3,000:1, a department has experienced a series of seemingly unrelated incidents, all of which form the building blocks to a significant loss (Figure 1). The question is, “Is anyone keeping count?” Is the department at number 299 in “At Risk Behaviors,” and comfortably distanced from an LODD? Or has the 29th “Lost Workday Injury” occurred, placing the department on the precipice of an LODD? Could the next run be “the one”? And finally, is the countdown limited to just one’s own fire department, or are the numbers cumulative on a larger scale?

Repeating mistakes

Few departments have served their communities for any length of time and not had an injury event that was a heartbeat away from joining the “sad fraternity.” Yet with all of these signals and seeming randomness, there is an identifiable repetitiveness to the LODD incident. This repetitiveness baffles injury epidemiologists, sociologists, data wonks, fire chiefs, firefighters and survivors. How do we (the fire service) end up with LODD events that look, sound and feel so familiar? It seems that the “full-circle learning” used by other high-risk industries remains elusive to the fire service.

There are a number of factors that contribute to this repetitiveness. One significant factor that prevents full learning from another department’s LODD is organizational relativity. Officers and department members from the chief’s office to the probationary firefighter are lulled into a sense of “that couldn’t happen here” syndrome because the factors that LODD reports tend to focus on (e.g., occupancy type, staffing, response package, training, tactics, command system) are mismatches to one’s own department. A mindset develops that because comparative factors don’t line up identically, then “it couldn’t happen here.”

A second factor that affects the full learning process is generational relativity. Well-known LODD events (e.g., Vendome Hotel, 23rd Street, Waldbaum’s, Hackensack Ford, Worcester Cold Storage, Far West Truck and Auto Supply, Sofa Super Store) for one generation of firefighters are virtually unknown, or become passing trivia by firefighters of subsequent generations. Even the affected department can reach a state where the LODD event seems like it was from another time in another world. One example of the phenomenon was the discussion of the Wade Dump fire in Chester, PA, which I wrote about in a previous article about historic fires. Several firefighters I have spoken with since the article was published had no knowledge of the fire, primarily because they had not even been born at the time of the fire.

Two people involved in the fire service have made similar observations that will set the tone for the rest of the article. The first is FDNY Deputy Chief (ret.) Vincent Dunn, who observed, “There are no new lessons to be learned from a firefighter’s death or injury. The cause of a tragedy is usually an old lesson we have not learned or have forgotten along the way.” The second is Dawn Castillo, director of the Division of Safety Research at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Castillo was addressing a meeting of chiefs who were loudly complaining about the repetitiveness of findings in NIOSH LODD reports. When the fury of the chiefs died down, she succinctly observed, “You [the fire service] are not inventing any new ways to kill yourselves.”

The most frequent danger

With those observations as framework, let’s now focus on three LODD events in single-family dwellings—the most frequently encountered structure fire that kills firefighters—from different decades. As you read the article, there are two learning tools to apply to the events that will expand your knowledge of them and further efforts to prevent a recurrence. The two tools are “shoe-shifting” and “chunking.”

Shoe-shifting is the ability to put yourself in another’s shoes. For the purpose of this article, plug actual elements of your department into the events (e.g., your department’s Engine 1, A Shift, as the engine that loses a firefighter). Chunking is the process of taking individual pieces of information and grouping them into larger units. It improves the amount of information one can remember. Applying these two tools will overcome the barriers of organizational relativity and generational relativity. The exercise can be repeated with any seemingly unrelated group of LODD events.

The three fires selected for review occurred in diverse locations. Studied independent of one another, they appear to be isolated, unrelated events. Yet when the tragedies are overlaid and taken in total, multiple similarities surface that company and command officers should note and commit to memory as part of preparing for the next response to a single-family dwelling fire. One of the most striking lessons is taking into account the effect of flow path on fire development. Unless we make a more concerted effort to consciously “chunk” events, and learn from the past, Dunn and Castillo’s observations will continue to be self-fulfilling prophesies. We owe it to Firefighter Anthony Phillips (age 30 at time of death), Firefighter Lewis Matthews (age 29 at time of death), Firefighter Kyle Wilson (age 24 at time of death), Lt. Vincent Perez (age 48 at time of death) and Firefighter/Paramedic Anthony Valerio (age 53 at time of death), and their survivors, to do better. (Note: Anthony Phillips would be 48 years old this year. Lewis Matthews would be 47 years old. Kyle Wilson would be 34 years old. Vincent Perez would be 54 years old. Anthony Valerio would be 59 years old)

Incident 1: Cherry Road Fire

Location: 3146 Cherry Road, NE, Washington, DC, May 30, 1999

Synopsis: On May 30, 1999, the District of Columbia Fire Department was notified of a structure fire at 3146 Cherry Road, NE. Four engines, two ladders, one rescue and one battalion chief responded. First-arriving companies encountered a working fire in an end-unit townhouse.

The initial attack line and a backup line were advanced through the Alpha side door. Other companies proceeded to the Charlie side and observed a working basement fire. The basement sliding glass door was broken out by one of the companies operating on the Charlie side, creating a large opening that allowed a torrent of fresh air to feed the fire. The crews on the first floor had the Alpha side door open and had opened the door at the top of the stairs, creating an unimpeded flow path. The fire intensified dramatically and the flame front from the fire rushed up the stairs fatally injuring Firefighters Phillips and Matthews. Three other firefighters on the first floor were injured.

More information about the Cherry Road Fire can be found at these resources:

- DC Fire & EMS Department Report from the Reconstruction Committee: www.10engine.com/news/download/file_id/4712

- NIST Engineering Laboratory: Cherry Road Townhouse Fire, Washington, D.C., 1999: http://www.nist.gov/el/disasterstudies/fire/cherryroad_dc_fire1999.cfm

- Cherry Road Fire: Lt. Joe Morgan’s Story: www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrXdYPKrUJY

Incident #2: Marsh Overlook Fire

Location: 15474 Marsh Overlook Dr., Woodbridge, VA, April 16, 2007

Synopsis: On April 16, 2007, the Prince William County Department of Fire and Rescue was notified of a structure fire at 15474 Marsh Overlook Dr. Three engines, one tower ladder, one medic unit, one ambulance and one battalion chief were dispatched. A rescue and the department safety officer self-dispatched. Arriving crews observed a working fire in a 6,000 sq.-ft., two-story, single-family dwelling. The initial report was “heavy fire, sides B and C.” A second alarm was requested.

The first two arriving companies entered the structure to perform a primary search and initiate fire attack (with a 2.5-inch attack line). A 25–35-mph wind (with 50-mph gusts) was blowing from the Charlie side. Escaping occupants left the Charlie side doors open when they escaped prior to fire department arrival. The Alpha side door was open as the initial entry point, “… creating a chimney effect in the center core of the structure” (Marsh Overlook Report, 2007).

Firefighter Wilson and his officer were searching in the second-floor master bedroom when conditions changed instantly from smoke at the ceiling to blackout, high heat and instantaneous fire involvement. Firefighter Wilson and his officer became separated, with Wilson becoming trapped and disoriented. The flow path, supported by the high winds, created blowtorch conditions in the stairwell and explosive involvement and subsequent collapse of the lightweight constructed structure.

Additional information about the Marsh Overlook Fire can be found at the following resources:

- Prince William County, VA, Technician 1 Kyle Wilson LODD Report: www.pwcgov.org/government/dept/FR/Pages/Technician-I-Kyle-Wilson-LODD-Report.aspx

- NIOSH Report: Career Fire Fighter Dies in Wind Driven Residential Structure Fire – Virginia: www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200712.html

- Prince William County (VA) Fire Rescue Kyle Wilson LODD 2007—Is This on Your Radar Screen? www.firehouse.com/10459541

Incident #3: Berkeley Way Fire

Location: 133 Berkeley Way, San Francisco, CA, June 2, 2011

Synopsis: On June 2, 2011, the San Francisco Fire Department was notified of a structure fire at 133 Berkeley Way. Three engines, two ladders, a heavy rescue squad, an ambulance and three battalion chiefs were dispatched. The first-arriving engine reported a three-story residential structure with light smoke showing. The crew entered the structure with a hoseline to locate and extinguish the fire.

During the search for the fire, the battalion chief of the attack group made contact with the crew and advised them that the fire was likely one floor below. The sliding glass doors one floor below the crew failed, allowing a massive inrush of air that intensified the fire, completed the flow path and killed Lt. Perez and Firefighter/Paramedic Valerio.

More information on the Berkeley Way Fire can be found at the following resources section:

- San Francisco Fire Department Safety Investigation Report, Berkeley Way LODD: http://tinyurl.com/SFFD-LODD-Report

- NIOSH Report: A Career Lieutenant and Fire Fighter/Paramedic Die in a Hillside Residential House Fire – California: www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face201113.html

- NIST: Simulation of a Fire in a Hillside Residential Structure—San Francisco: www.youtube.com/watch?v=pgDbsv62cu8

Key takeaways

As noted, when these three tragedies are looked at together, one of the key similarities is the effect of flow path on fire development. It is vital that fire service leaders take time to understand the current research about flow path and pass the information to their members. See the references section below for some great resources for flow path research.

The residential structure fire in single-family dwellings is our high-frequency event. Because of this frequency, the likelihood of a fire department experiencing a LODD is higher than for other occupancy types. Fire service leaders have an obligation—written in the epitaphs of Anthony Phillips, Lewis Matthews, Kyle Wilson, Vincent Perez, Anthony Valerio and far too many others— to ensure that their members honor these losses.

Following are a handful of actions leaders can take to help ensure the safety of their crews:

- Frequently review these tragic events.

- Remember that each of the firefighters lost was engaged in actions they had collectively performed countless times before in training and actual fire conditions.

- Reinforce that structural fires are hostile events that are subject to laws of physics and chemistry that outpace the ability of human reaction time. Harnessing the event, even countless times, is no guarantee the next event will conform.

- Understand that even coordinated firefighting efforts are subject to uncontrolled reactions of the fire.

- Revisit lessons from past events, learning from the experience of others and an in-depth immersion in emerging science and information are three barriers that will place additional distance between your members and an LODD.

Taking action to ensure that your crews understand lessons learned from some of the most high-frequency fire scenes they face will better prepare them for handling common dangers.

References and resources

Cherry, K. What is chunking and how can it improve your memory? 2015. http://psychology.about.com/od/cindex/g/chunking.htm.

Firehouse Magazine Supplement: Fireground Tactics Based on Research. November 2015. Firehouse.com/12275342.

Sherman, J. Empathic intelligence: To put yourself in their shoes, unlace yours. 2009. www.psychologytoday.com/blog/ambigamy/200905/empathic-intelligence-put-yourself-in-their-shoes-unlace-yours.

UL Firefighter Safety Research Institute. Impact of Ventilation on Fire Behavior in Legacy and Contemporary Residential Construction. May 2013. http://tinyurl.com/ul-vent-construction.

UL New Science. Interrupting the Flow Path. Winter 2014. http://newscience.ul.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/NS_FS_Article_Interrupting_Flow_Path.pdf.