Overcoming the Barriers that Prevent Near-Miss Reporting

Does your department report and act upon near-miss events? If not, you’re missing a prime opportunity to prevent, rather than react too, the occurrence of “accidents.” Research has shown that for every accident (an unexpected, unplanned event which may or may not result in a loss) a number of near-miss events precede that event. Major industries such as health care, petrochemical, and aviation use near-miss reporting to effectively identify and eliminate unsafe practice or behavior, and modify administrative control.

The under reporting of near-miss events is reported to be common in general industry. For example, a high rate of under reporting was found following a 12-country systematic literature review which suggested the average rate of under-reporting of adverse drug events was as high as 94 percent (Hazell & Shakir, 2006).

Bernard Borg’s research suggests that for every reported injury, 30 near-miss events have occurred leading to that injury. This data is conservative when compared to studies conducted by Frank Bird, which concluded that for every major injury (fatality), there are 10 minor injuries, 30 equipment damage and 600 near-miss incidents (Borg, 2002).

The fire service is not immune from this low reporting of near-miss episodes.

Near misses in the fire service

If we apply the 63,350 firefighter injuries as reported to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) in 2014, using Borg’s conservative calculation, we find that 1,900,500 near-miss events occurred. That's an astounding number of close calls. If relying on reported incidents alone, fire administrators are cautioned about their true accident experience, underestimating the impact of safety-related incidents in terms of severity and number.

In 2005, the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) launched the National Firefighter Near-Miss Reporting System for the American fire service. Since that time, approximately 5,000 reports had been entered in efforts to educate others in near-miss experiences.

The National Safety Council defines a near-miss as an unplanned event that did not result in injury, illness, or damage; but had the potential to do so. These “close-calls” occur frequently in high-risk industries and indicate an area of elevated risk potential of incident occurrence.

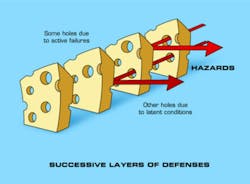

One way to view the chain of near-miss events is to imagine layers of Swiss cheese. A popular accident causation model, developed by James Reason states that if we place layers of Swiss cheese on top of each other, with each layer representing a near-miss, that eventually all the holes of the cheese will align and an accident will occur (Perneger, 2005). Reason further theorized that if we interrupt this chain of near-miss events through preventative controls (administrative, engineering, protective equipment, elimination) an accident will be avoided.

The fire service, as with other high-risk industries, are full of “close calls.” Progressive fire agencies consider these close calls as opportunities to prevent a future loss from occurring. Departments that actively document and apply the lessons of the near-miss recognize the value that these close calls represent; vulnerabilities in the system. In turn, these progressive departments apply the lessons learned to future operations.

Why under reporting?

If near-miss events are underrepresented in the overall injury statistics, then how can the fire service overcome this barrier and have better confidence in their true injury experience reporting? The answers lie in revealing some common causes of under reporting.

The compassionate quality of caring for others and placing service before self lies at the heart of the American fire service culture. To accomplish the fire service mission of service before self often requires the firefighter to assume a greater level of risk and accept this danger as “part of the job.” This tolerance of elevated risk may dull the need to report what to many view as a close call, but to the firefighter, just an accepted part of the job. Thus, under reporting of near-miss events occur. From a cultural perspective, an acceptance of risk is expected. Though this risk tolerance is admirable, and required at times, steps must be taken to minimize exposures, which jeopardize others to unwarranted danger through over-aggressive actions. The need to report near-miss events should be encouraged to reduce the possibility of tragic accidents due to over-aggressive behavior. Complacency and a failure to apply appropriate control measures exposes others to needless risk.

The fear of reprisal or retaliation is a common cause for the under reporting of near-miss events. Those organizations which actively use a near-miss reporting system do not assign disciplinary measure to those reporting. In aviation, punitive measures are not taken when an employee reports a near-miss through the Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS). The fact of risk-free reporting has changed the landscape of accident reporting in the aviation industry and has resulted in safer air travel. A Just Culture, as describe by Sydney Dekker highlights the importance of identifying the root cause of a mishap, and reward those who report. A Just Culture is one where employees are not fearful of making mistakes, and feel comfortable reporting their observations (Dekker, 2007). Absent fear, lessons are shared, root causes are identified and real fixes can be put into place (Gasaway, p. 129). Applying the lessons from aviation of incorporating a confidential, non-penalizing reporting system inspires open reporting.

Streamlining the reporting process and assuring anonymity helps to increase reporting. Simplifying the reporting process through readily available reporting systems (technology) is useful. Inefficiencies such as eliminating a need to report to a supervisor, reporting taking too long and not requiring duplicity in reporting (multiple “safety” reports) are important elements of an effective near-miss reporting system.

Consequences of reporting

Incident investigation, documentation and follow-up demonstrates a desire to share and learn from near-miss events. This reassures those reporting that their being heard; their efforts paid off. Communicating the result of the near-miss investigation is a sign of transparency in safety reporting.

An unintended consequence of reporting may be a perception of competency or skill being questioned of the person who reported the near-miss. This spillover effect can be detrimental because a negative perception held by others (peers and management) of those involved in the near-miss report unintendedly projects a message of non-support of the member and of the reporting system. Some may question the ability of the member to handle difficult situations and go even as far as to assign blame, i.e. the reporting party was the cause of the near-miss event. This perception of “blame” is unfortunate, and is a factor that forms a barrier to effective reporting.

When reporting near-miss events, it becomes important that the organization report both minor and major incidents. Avoiding report bias (selective reporting), a tendency to under report unforeseen or adverse finding while preferring another, more favorable outcome is so that reports may be linked, with common causes identified. A “full” investigation and publication of near-miss findings is fundamental to learning.

As with all initiatives, planning the implementation of a near-miss reporting and evaluation system is important to success. Creating an understanding of the near-miss system; how it’s used, why we want to track close-calls, what type of event qualifies, who can initiate the report and how the information will be communicated within the department. The fear of disciplinary measures for those who report and the mistaken belief of placing blame should be addressed early in the planning process. Your program planning should include a near-miss program overview, answering those who, what, when, where, why, etc. questions. Provide training to ensure consistent investigation and reporting, a review of policy, practice, equipment and human factors related to the close-call and how to communicate results. Your goal is to learn, communicate and prevent reoccurrence.

In closing

Fire departments actively using the national near-miss system have found that they’ve been able to identify deficiencies in the training, station and operational operations. Modifications to policy, equipment, practice and in human factors are the outfall of a near-miss reporting system. Incorporating a near-miss system into your overall safety management program will not only enhance firefighter safety, but also project a positive image that department leadership indeed cares for their first responders.

See Kline at Firehouse Expo 2016—Richard Kline will be presenting "Training Safety Officer Program: Managing Risk on the Training Ground" during Firehouse Expo, Oct. 18–22, in Nashville.

References

- Borg, Bernard (2002). Predictive Safety from Near-Miss and Hazard Reporting, signalsafety.ca/files/Predictive Safety-Near-Miss Hazard Reporting.

- Dekker, Sydney (2007). Just Culture: Balancing Safety and Accountability. Ashgate Publishing, Burlington, Vermont

- Gasaway, Richard. (2013). Situational Awareness Matters, Volume 1, Gasaway Consulting Group, LLC. St. Paul, MN.

- Hazell l , Shakir SA. (2006 ). Under Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions: A Systematic Review. Drug Safety, 29, 385 –96.

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), 2014 US Firefighter Injuries. Issue date: November 2015. http://www.nfpa.org/news-and-research/fire-statistics-and-reports/fire-statistics/the-fire-service/fatalities-and-injuries/firefighter-injuries-in-the-united-states.

- Perneger, Thomas. (2005). In The Swiss Cheese Model of Safety Incidents: Are There Holes in the Metaphor? Retrieved April 12, 2016, from ncbl.nlm.gov. BMC Health Services Research.

RICHARD C. KLINE MS, EFO, CFO is 39- year fire service veteran. Kline recently retired from the City of Plymouth, MN, Fire Department following 23-years of service as fire chief. Kline is a frequent regional and national speaker, presenting on topics relating to command competencies and firefighter safety and health. Chief Kline may be contacted at [email protected].