Editor's note: I spoke with New Orleans District Fire Chief Chris E. Mickal on the telephone numerous times to get a sense of what the local firefighters had to deal with during and after Hurricane Katrina. I had been in New Orleans on business for four days, leaving the Friday before the hurricane struck. Chief Mickal gave me an extensive tour of the city, then by telephone he shared the following account.

The First Platoon was held over to remain in quarters with the on-duty Third Platoon. Each District (Battalion) moved apparatus out of the fire stations to higher ground or a safe place of refuge. Downtown units went to a hotel loading dock and companies in outlying areas parked at condominiums.

At 6 P.M. Sunday, it started to become windy. By 9 P.M., the entire department had relocated to their safe places of refuge. Units were to stop responding when the winds reached 45 mph. This had taken place before previous storms, but those storms missed the city.

At midnight, winds topped 100 mph. At 4 A.M., a piece of wood shattered the window of a room where several firefighters were located. Hurricane-force winds were blowing into the room. Firefighters and guests were standing in the hotel lobby. Windows were breaking and it was difficult to find a safe place to stand. The winds were blowing through the hotel. After 5 A.M., the power went out. Fierce, wind-driven rain was tearing off the sides of buildings. The radio channels stayed up and units could talk among themselves. People were trapped in the elevators, so rescues were made in the hotel.

After 9 A.M., the hurricane passed and within two hours reports of fires were being received. Two companies that had taken refuge in a condominium complex near Lake Pontchartrain reported house fires. Chief Mickal heard over the radio that companies were unable to respond to these incidents because of the water. Mickal asked, "What water?" That's when the report was given about a break in the levee. Mickal said that when he heard that the levee broke, he knew that his life as he had known it was over. He lived two blocks away and the area was flooded in 15 minutes.

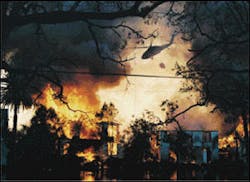

The water traveled south to the Superdome, seven to eight miles away. When the levee broke, the surge of water knocked the first block of homes off their foundations, snapping natural gas lines. The gas ignited, burning houses or just burning off above the flood waters.

Around noon, apparatus that could travel started a "windshield survey." Extensive damage was visible. Fire stations were checked and there was no electricity. Much of the fire department was moved to Lower Coast Algiers on the south side of the Mississippi River. The fire department and EMS were housed at a nursing home complex. Some units in outlying areas were stuck for up to a week at the locations where they had taken refuge. They made rescues of trapped civilians every day. On Tuesday morning, with reports of people trapped, firefighters grabbed boats and removed people day and night. About half-dozen apparatus broke down and some had to be left in the flood waters. Some rigs were still trapped by the flood waters closer to the lake.

When a fire was reported, units responded from their base in Algiers. It took them 10 to 15 minutes to cross the Mississippi River. Looking over the bridge, many times three and four columns of smoke were visible across the city. Some fires were in areas that were inaccessible. After looters broke into a four-story commercial building on Canal Street, they apparently started a fire. The first engine reported no water in the hydrant. Mickal ordered the engineer to drop his hard suction in the street and take suction from the flood water, which was several feet deep. Looters were in the next store while firefighters worked the fire, which extended to all four floors of the building.

Firefighters stayed together, but police officers were so spread out it was sometimes difficult to find them. Police cars, a fire department supply van and postal vehicles were stolen by those wanting to leave the city. Those vehicles were abandoned after reaching more flooded areas. Fire units operated at the scene until dark and then returned to their complex. Enroute to Algiers, firefighters saw a huge two-story building that was on fire and collapsed into the street. There was an unruly crowd, so units left the scene. A fire in a chemical plant burned a mile-long wharf.

Over the radio, a fire department captain coordinated with helicopters that were brought in to make water drops on fires. The captain told one pilot to make a drop on the left exposure and that is where the water was dropped. Responding to one incident by the time units arrived, the fire had extended to two or three buildings. Units had to operate in waist-high water. At one fire, eight two-story condominium units were involved.

Firefighters worked under many obstacles. There were no radios and the communications center was flooded. An antenna was rigged on a high-rise and dispatch was rigged from City Hall.

There was no water in the hydrants. The firefighters stayed together. There were massive fires, confusion and the firefighters' lives were threatened.

On one trip over the river, firefighters responding to a fire noticed another and called dispatch, which replied that it had not yet received a call on the new incident. That fire extended to 12 dwellings. All that was left were the chimneys.

Firefighters operating in the nasty water finally received new gear. They were decontaminated after every run. Law enforcement from around the country arrived to bring order. Firefighters from Illinois and Montgomery County, MD, responded with over 300 FDNY members. Federal incident management and support teams along with urban search and rescue (USAR) and swift-water rescue teams were deployed.

As the water receded, four New Orleans fire stations were usable during the daylight hours. At each station, engines ladders, tankers, decon units, rapid intervention teams, EMS and law enforcement responded as a team. At one fire station, the force of the water blew out the cinderblock walls. After looters started a fire in a florist shop, the fire extended to the fire department supply annex, destroying or damaging hose and other equipment. Some firefighters' personal cars were damaged when vandals broke into fire stations and destroyed anything of value.

Firefighters initially had to scrounge for food and clothes. Mickal said for the first time in his life he was hungry and didn't have anything to eat. After police took control of a looted store, the manager told police and firefighters they could have what ever they needed. Eventually, at the Algiers compound, 500 to 1,000 meals were served three times a day. Mickal had to wash his clothes in a garbage can. He said they were lucky to have food and shelter and no extras. They took cold-water showers and had been lucky to be living in the crude conditions. Military meals ready to eat (MREs) were used in the field. Gear was not allowed inside the buildings in the complex. There was a water purification plant in the Algiers neighborhood.

Many firefighters who responded to the city to help worked on firefighters' homes on their time off. Everybody was so tired that when other firefighters arrived they were a welcome sight. The radio traffic was unusual. FDNY firefighters requested a "10-75 for a working fire" where New Orleans says working fire. FDNY says "rubbish," New Orleans says "garbage." FDNY reports "we have a run," New Orleans says "we have a roll." FDNY uses "exposure 1, 2, 3 and 4," New Orleans says "A, B, C and D."

Up to 70% of the New Orleans firefighters might have lost their homes. New Orleans has a population of 500,000 in the 300-square-mile city. Of that area, half is underwater or marshland. Mickal said that even if he hadn't lost his home, the work was very stressful. Many of the firefighters are living paycheck to paycheck. They have to travel far distances to visit their families. Apparently, one or more cruise ships were to be brought in to house firefighters and first responders who lost their homes. Mickal said the firefighters stuck together as most all of the rest of city government fell apart.