High-Tension Rescue in Vigo County, Indiana

The victim: an average-sized man who seemed tiny from the rescuers' vantage point 475 feet below.

Alan Cook, 45, of Decatur, Ill., climbed up a 625-foot tower off Mulberry Road in northwestern Vigo County midday Tuesday to add wiring and an antenna. About 475 feet up, his co-worker Mike Norman said, "He quit answering me."

Cook had passed out. Using a cell phone, Norman called 911. Sugar Creek Fire Department units arrived on the scene a little past 1 p.m.

Cook, drifting in and out of consciousness and incoherent after awakening, could not lower himself.

Medical personnel at the scene did not know what was wrong with Cook. A stroke or heart attack had not been ruled out.

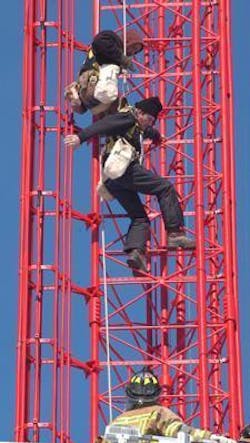

It was 19 degrees, with light but gusty winds adding to the temperature's bite. As Cook's dark figure silhouetted against a clear blue sky and the red and white steel of the tower, firefighters clustered around the south end of the base, soaking up the difficulty of the operation.

Firefighter Hidekatsu Kajitami -- "Kaji" [pronounced "codgy"] to his comrades -- started up the tower immediately, said Chief James Holbert, followed by Battalion Chief Paul Watson and Deputy Chief Darrick Scott.

Norman stayed with Cook until Kaji arrived at the top of his ascent. Even for a fit, healthy man, the burden of the equipment made it a painstakingly slow climb, rung by rung.

When Kaji got to Cook, Cook was still in his harness and hooked to the tower. Firefighters on the ground now had a rescue worker on the tower, and had to plot a way to bring Cook down that distance without at any point unhooking him from the lifeline. In his condition, having him loose for a moment could have led to disaster.

A ladder truck from Honey Creek Fire Department arrived about 2 p.m. With its 90-foot ladder, it will take almost a quarter off the descent. Now all the firefighters on the ground had to do was rig a rope system to lower Cook the other 385 feet -- more than the length of a football field, with end zones -- straight down.

As if to demonstrate the magnitude of the problem, one of Cook's gray work gloves came loose and floated lazily down, the wind carrying it off to the northwest as is dropped. It takes half a minute to hit the ground.

Chad Brackin, a Trans-Care paramedic, and his team watched from below, hoping firefighters will pass condition reports on Cook through Kaji.

As the rigging is pulled together, Cook is conscious but disoriented.

Norman, who had climbed all the way down, tells the firefighters that the amount of rope necessary to bring Cook down will weigh more than he does by the time they get him near the ground, so it will need to be carefully secured.

Rescue workers listen but don't need to be reminded.

At 2:27 p.m., they are ready to begin lowering Cook by using the hitch on the back of a truck, several hundred feet of life-safety rated rope and half a dozen firefighters to steady it through the pulleys.

The problem was that Cook wasn't ready. In his confusion, he apparently doesn't realize Kaji is there to help him, and isn't willing to let go. As rescue workers tried to lower him, he kept grabbing hold of the tower. At one point, he started back up, his movements jerky and uncoordinated.

Norman immediately headed back up to help comfort Cook. He scaled up the rungs with incredible energy, making more than 300 feet in just minutes.

"C'mon, Alan," he yelled, barely audible from the ground.

Cook, unwilling to let go, kept trying to climb down himself, so when Norman reached him, he had to keep moving the rope around so Cook couldn't grab the steel. Now gloveless in the freezing cold, it was hard to imagine how Cook could grip anything.

With Norman alongside Cook on the white and red steel, and Kaji clinging to the inside of the tower, Cook made the descent. His feet kicked at the rungs, trying to move himself.

At 3:08 p.m., Cook reached the bucket at the top of Honey Creek's ladder, and firefighters gathered him aboard. Medics are waiting at the side of the truck, with a gurney, to begin treatment.

Cook is quickly reclined, strapped down and given oxygen. He is awake but distant, as though he isn't aware of what is going on around him. He was taken to Union Hospital, where officials said no updates on his condition were available.

Watson and Scott got on the ground ahead of Cook, both obviously chilled to the bone. They warmed up in an ambulance, then emerged to watch the end of the operation.

The two gave all the credit to Kaji, who no sooner got his feet on the ground before he was showered by congratulations from his fellow firefighters.

He was placed in an ambulance, too, and taken to Regional Hospital, where he was kept for several hours under observation. Holbert said Kaji had a slight fever, and was being given fluids.

"You're trained to do things right away," Holbert said. In this case, a quick fix simply isn't possible. "You can't save anybody if you get hurt yourself."

The height, the awkward placement and the cold, Holbert said, all compounded the difficulty.

Scott, looking up into the cold winter sky, said, "You train for this, but ... Passing the red light [about 200 feet up], I thought, 'That's for airplanes.'"

Related