The Forgotten Fire

In 1908, a fire in a crowded auditorium in the small town of Boyertown resulted in Pennsylvania’s greatest fire disaster. One hundred seventy people died. The Boyertown Opera House fire is listed in the World Almanac as one of the major fires of the 20th century.

As a result of this fire, doors in public buildings now open outward and fire escapes must be floor level and clearly marked.

Yet the fire is largely forgotten, buried in the yellowed pages of old newspapers and the fading memories of aging townspeople.

The circumstances are tragic enough: A sudden fire erupted in an overcrowded second-floor entertainment hall. Within 30 minutes, 165 people, still trapped in the building, suffocated. As the fire raged unchecked, the victims were so terribly burned that it took five days for relatives to identify them. Twenty-five never were identified. Of the 200 who escaped, four died later of their injuries. One firefighter was killed when a hose cart crashed on the way to the fire scene.

The disaster struck at the heart of country town of 2,500 people. No family was left untouched.

how did it happen?

What caused the fire and why did so many people die so quickly? A set of circumstances, a combination that had not occurred before and was never repeated, produced a unique situation. Hydrogen gas, which had escaped from a calcium light projector in the auditorium, in addition to a small kerosene fire on stage, produced a sudden explosion of fire in the air. Because the doors opened inward, many in the audience, in panic, were trapped at the entrance to the second-floor auditorium. The press of the crowd resulted in a fiery prison from which they could not escape.

On Monday, Jan. 13, 1908, the small Pennsylvania Dutch town of Boyertown was alive with excitement about the play to be presented at the Opera House that evening. A traveling company brought the play to town and was using local people as actors and actresses. The site of the play, the Opera House, was part of a substantial three-story brick building. The first floor contained a bank and a hardware store. An entertainment hall, the “Opera House,” was on the second floor, while the third floor was used as a lodge meeting hall. Electricity had not yet come to Boyertown in 1908. The building was lit by kerosene, and kerosene footlights edged the stage.

On that Monday night, 312 people crowded into the auditorium. As eager families and friends climbed the familiar stairs from a central doorway to the second-floor auditorium, they had no inkling of the disastrous circumstances lay ahead.

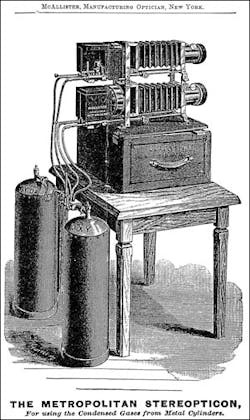

As part of the traveling show, slides were shown between the acts of the play. The traveling company had brought along a calcium light projector, known as a Ster-eopticon. Calcium light projectors were in common use for “magic lantern” shows in communities without electricity. Their light was produced by combining compressed hydrogen and oxygen. The compressed gases from the tanks flowed into the projector through small tubes. An experienced operator was needed to set up the projector properly and to combine the gas in the right mix. If one of the tubes came loose from the tank during the show, the light would fail and the escaping gas would produce a loud hissing noise.

A problem had arisen. The projector’s regular operator had not arrived in town with the traveling company. In his place was a young man who had been given only a few days’ training on the complicated machine. It was his first night on the job. It also turned out to be his last.

As he was showing slides between acts, the unthinkable happened. The tube to one of the tanks got loose and the gas escaped. Through a series of strange circumstances, it was never determined at the inquest which tank had the loose tube. But because of the nature of the fire, it is presumed to have been the hydrogen tank. The loosened tube produced a loud, hissing sound.

The audience in the darkened auditorium grew restless. Those in front turned around to see what was happening.

If only the hydrogen had escaped, the disaster would not have occurred. A second circumstance produced the tragic combination.

Waiting for their next act, the actors behind the closed curtain heard the noise in the auditorium. Someone pulled the curtain apart and several actors moved to the front of the stage. In the confusion, one of them kicked over a kerosene footlight, and a small fire started on the stage. It then spread to the kerosene tank.

Already restless because of the hissing, the audience saw the fire and panicked. Many rushed to the auditorium stairway at the back of the room. The first group was able to get down the stairs to safety. But since the doors opened inward, the pressure of more people against the doors forced them shut. The people were trapped.

While the small fire on the stage added an element of danger, it did not produce the disaster. If only the small kerosene fire had occurred, many more the audience would have been able to get out of the auditorium safely, in spite of the problems with the door. There was a secondary stairway beside the stage and two fire escapes that were not marked and people had to scramble out the windows to get to them. But with more time, those trapped at the auditorium doors could have changed their escape route.

Within 30 minutes of the start of the kerosene fire, the deadly combination of the escaped hydrogen and the open flame, produced an explosion in the air spelled disaster for those still trapped inside. Miraculously, 200 people had gotten out of the building before the explosion.

Quickly, the town’s two fire companies were called. Volunteers from the nearest company, only three blocks away from the fire scene, decided not to spend time getting horses from the livery stable, but pulled the hose cart themselves. Unfortunately, the street, formerly dirt, had just been paved. The hose cart went out of control on the slippery downslope and crashed into a tree. A young firefighter, the father of two small sons, was killed in the accident.

Firefighting volunteers, without their hosecart, rushed to the burning building, where they helped a few of the final survivors get out. By the time the second firefighting crew arrived, the whole building was burning out of control.

The firefighters turned to a neighboring town for help. A steamer and hose cart were loaded onto flatbeds and taken by train for the 10-mile trip to Boyertown. The 50 firefighters who came along declared the fire under control by 4:15 A.M. Tuesday. They also stayed through the day to help recover the bodies. Their firemen’s ladders were used to bring the dead from the second-floor ruins.

The fire made the front page of all the Philadelphia newspapers. By Tuesday morning, the town was filled with reporters and photographers. The morbidly curious and the casual sightseer mingled with grieving relatives in a week of turmoil. By Thursday, as many as a dozen funerals were being held each day. The following Sunday, the community held a service for the 25 who could not be identified. They were buried with dignity in the town cemetery less than a half mile from the fire scene.

Even before the inquest was held, the fire produced safety concerns throughout the state. Two days after the fire, Philadelphia’s mayor asked his fire marshal to check all theaters for unsafe conditions. The Philadelphia City Council passed a resolution to close all second-floor theaters if they posed a danger.

By the time of the inquest two weeks after the fire, the reporters and photographers had gone. The disaster was no longer news. The coroner’s jury listened to 50 witnesses in two days of testimony, some of it confused and contradictory. Deliberating four hours, the jury reached its decision. It declared two people criminally negligent: the play’s producer, for hiring an incompetent projector operator; and the state factory inspector, for failing to enforce existing fire safety laws. Neither was ever indicted in a court of law.

One year later Pennsylvania’s legislature passed laws requiring that doors open outward and fire escapes be at floor level and clearly marked. And second-floor theaters were no longer built.

private grieving

What about the community of Boyer-town? The crowds went home. School reopened, with 25 empty desks. Workers returned to the workbench beside empty places. Homes and farms were sold. Orphans moved in with their grandparents.

Slowly the townspeople picked up the shattered pieces of their lives and went on. But beneath the outward activity there was an inward mood of private grief.

In the years that followed the fire, the community’s grieving went behind closed doors. Many people never talked about the fire again in their lifetime. Boyertown wrapped its greatest disaster in silence and survived.

Mary Jane Schneider is the author of the book, A Town In Tragedy, about the Boyertown fire. Copies of the 232-page softcover book may be purchased for $16.90 each from MJS Publica-tions, 23 East Orchard Hills Drive, Boyertown, PA 19512.