As early as the late 1990s, Australian fire services began to adopt a Swedish approach to structural firefighting techniques and tactics. This followed a similar move in the United Kingdom and some other parts of Europe. This approach included implementing a live-fire training program known as Compartment Fire Behaviour Training (CFBT) where a sound understanding of fire behavior became the driving force behind our decisions and actions on the fireground. My own organization has been training firefighters this way since 2003.

The concept of “non-negotiables” is an attempt to provide an all-encompassing doctrine that establishes clear guidelines for implementing the critical task-level skills that had been taught during CFBT. It is designed to add clarity to the gray area in every modern firefighter’s mind where “what must be done” and “it depends” exist uncomfortably side by side.

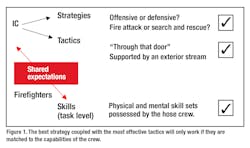

Training for shared expectations

Essentially, the IC is assessing where the fire is now, where it will be in the near future (usually measured in minutes), and what can be done with the resources at their disposal to mitigate the situation as quickly, safely and efficiently as possible. This process is time-critical and will rely heavily on experience, knowledge and a realistic and honest understanding of their crew’s capabilities. This last element is crucial to safe and effective firefighting. Even a very knowledgeable and experienced IC will very like get this “equation” wrong if they do not realize the capabilities (or lack thereof) of their firefighters.

These concepts can be better explained in Table 1. First, the IC decides on a strategy. Generally, this is accepted as being either offensive or defensive. In most cases, entering a burning building for the purposes of fire attack or search and rescue would be considered an offensive attack.

The second decision involves selecting the tactics necessary to implement the chosen strategy. An example of a tactical decision would be to use one entry point over another or support the interior attack with an external stream.

While deciding on the correct strategy and associated tactics, the IC must balance this against the capabilities of the hose crew. It should be obvious that a mismatch in this area will jeopardize the success of the attack and increase risk, maybe even to the point where the interior environment becomes an unsafe workplace. It therefore becomes critical to ensure that these factors are aligned. If we assess all three accurately (strategy, tactics and task-level skills), then we ensure a safer workplace and increase our chance of success in the endeavor.

Who sets these expectations?

The only way to ensure shared expectations is to train as a team and establish standard or routine work practices. As you can imagine, this poses significant challenges for officers who have not yet (or will never) get the opportunity to really know the true capabilities of their crew.

Acquiring and maintaining the skills needed to ensure a safe workplace does not occur by accident or by just going to fire calls. These skill sets include theoretical knowledge, practical application of techniques and physical capability. All of these skills sets are perishable and require ongoing maintenance. To be truly proficient, most practical techniques should be practiced until routine. The more routine, the more likely that they will be used as required at real incidents and under stressful conditions.

What are appropriate expectations?

One way to look at this question is to ask what you would expect of a firefighter who has turned up to a fire in your house, with your loved ones and your property. It doesn’t get much simpler than that. Ask yourself what that firefighter looks like and is capable of—and be that firefighter.

This concept should be used as a constant benchmark when deciding what level of expertise is appropriate for setting realistic expectations. If you expect firefighters to mask-up in 20 seconds, stretch hose from the flaked tray in equal time and attack the fire with the speed that comes from practice and knowledge, then be that firefighter.

It depends (or does it?)

It has become useful in recent years to say, “it depends” when discussing what tactics and techniques are best for any given situation. Fundamentally true, this phrase is a reaction to the traditional method of training firefighters that was very prescriptive. This was in an attempt to provide “black or white” routine responses to most standard situations. It often followed a step-by-step formula that was rote learned, usually as a rookie. It allowed for rapid training but meant that firefighters struggled if conditions did not match their exact training scenarios or experience.

Unfortunately, “it depends” is also not the complete answer. I believe that the most effective firefighting philosophy lies somewhere in the middle. There are some things that must be implemented during offensive attack operations in order to stay safe and be effective. These can be described as task-level non-negotiables.

Non-negotiables

With reference to the “shared expectations” between officers and their firefighters, these non-negotiables represent an assurance to the IC that, once committed to interior firefighting operations, the hose crew will control the environment, stay on task and continue to monitor the prevailing fire conditions.

I believe the following non-negotiables are required at any structural fire incident where hose crews are operating. It doesn’t matter whether it is a small residential fire or a large commercial fire. The non-negotiables are scalable and represent best practices in that environment. They form the minimum expectation between battalion chiefs and captains as well as captains and firefighters (and also among firefighters on a hoseline).

All members on the fireground rely on each other to provide compliance. For example, the firefighter in control of the branch has an obligation to cool fire gases, not only for their safety but also the safety of colleagues hauling hose and any other firefighters within the structure. We all have a responsibility to do what is required for the safety of other firefighters on the fireground.

So, what are the non-negotiables?

· Stay low

· Control the flow path

· Cool the gases

· Put water on the fire ASAP

Despite the basic nature of each non-negotiable, they all require specific theoretical and practical knowledge to master. This important underpinning knowledge is shown in each of the images. This knowledge forms the basis for creating a targeted training program.

Stay low

The first and most basic non-negotiable is stay low, the importance of which cannot be overstated. Unfortunately, many firefighters only believe it’s necessary to stay low if it is too hot. Apart from the obvious subjectivity of this belief (what’s too hot?), there are many reasons why staying low makes a firefighter safer and more effective. These include:

· More effective search. Victims are generally on the floor.

· More stable posture in low visibility.

· Most effective way to use your personal torch (flashlight). Hold low and direct the beam along the floor (locate victims, obstacles).

· Better visibility (more chance of being below the smoke layer).

· Avoid pitfalls, stairs, etc.

· Reduce the chance of PPE becoming heat-drenched.

Non-negotiable: The default position during any interior fire attack is down low.

Control the flow path

In a compartment fire, flow path is the movement of hot gases between the fire and exhaust openings and the movement of air towards the fire. Firefighters must understand the relation between the inlets and outlets and realize that additional air feeding the fire will increase heat release rate.

Non-negotiable: Control the access of fresh air to a vent-controlled fire.

Cool the gases

The consequences if you cool the fire gases when you didn’t need to? Zero. The consequences if you should have cooled the gases but didn’t? Could be dire. The problem is in the name. Gases do not need to be excessively hot to ignite; it’s about mixture as well. Placing water (fog) into the smoke not only cools but also inerts the smoke, making it non-flammable.

Non-negotiable: Cool the gases aggressively. You have nothing to lose but everything to gain.

Put water on the fire ASAP

Due to modern materials, fires now put out more heat and spread more rapidly when given enough air. More than ever, there is a need to get sufficient water on burning materials as soon as possible. It is critical that firefighters understand how water extinguishes if they are to be as effective as possible.

Non-negotiable: With no visible victims or better information, the first line in should be fire attack. Remember, a fire attack team never ignores a victim and a search and rescue team never ignores a fire.

Training to meet expectations

Most, if not all, structural firefighting tactics and techniques fall under our four non-negotiables. By using these linkages, a crew can look at where they need to provide more training time or seek additional knowledge. Work may be needed in the theory components or practical elements or maybe a combination of both.