One of the most significant advances in resources for hazmat response since Ron Gore and the Jacksonville, FL, Fire Department started the first fire service hazmat team in the 1970s is the drone. The device’s continual improvement—as well as that of the software that drives it—means the addition of better monitoring and on-scene and post-incident capabilities.

Purchasing drones and associated equipment is expensive. However, by including multiple agencies, the cost can be reduced greatly for individual jurisdictions. (Drones aren’t just for hazmat or fires. They have purpose in all types of emergency response by all types of agencies. Some departments, such as the Corpus Christi, TX, Fire Department, have dedicated aerial units that are available to respond jurisdictionwide.) Private organizations within a community also can be sources of funding.

In the summer of 2021, I visited the Richmond, IN, Fire Department (RFD) to learn about its recently enacted drone program.

I have noted in the “Hazmatology” column that during my travels across the United States that I have found very close working relationships between police and fire departments in some jurisdictions. Richmond is one of those locations.

Fire Chief Jerry Purcell and Police Chief Michael Britt have decades of experience serving the city of Richmond and its citizens. Britt was somewhat skeptical about the idea of a collaboration between his department and Purcell’s when he was approached by Purcell, but now he is very excited about the relationship.

The COVID pandemic played a role in bringing the police and fire departments closer together. Police and fire personnel also found themselves working together on a more regular basis when the fire department took over EMS service a few years ago.

Britt also indicates his belief that the younger generation that’s coming into both departments helps to produce a better working relationship. “No one told the new personnel that fire and police don’t get along,” he tells Firehouse Magazine.

So much the better when a drone program was conceived.

In 2016, the RFD was contacted by the Wayne Bank and was offered a $40,000 grant to start a drone program. Initially, the RFD researched other fire departments and their drone programs, including a visit to the Wayne Township Fire Department (WTFD) in Indianapolis. That department initially purchased five DJI drones and three cameras. Drones included three Phantom 4 Pros and two Inspire 1 v2.0s. Also purchased were iPad minis for each drone. Plans are in the works by the department to obtain another drone that has greater infrared camera capability and to add air-monitoring capability.

Within two months, the WTFD’s program was in operation and used drones on a commercial building fire. This followed training and obtaining the necessary Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and local permits to operate the drones.

The RFD has three Certificates of Authorization (COA). The process of obtaining the COAs for the department’s program was a long one, but the FAA was very helpful during the process to ensure that the paperwork was done properly. The three COAs are required to be renewed every two years. The FAA required emergency procedures to clear the COA process.

One of the first problems that the RFD encountered with the drones themselves was the video capture on their controller. The screen was very small, which made gathering around it difficult for those who needed to see footage from the drone’s camera(s). The department purchased upgraded controllers that had the capability to connect to a 24-inch (or larger) computer screen for video output.

An old ambulance vehicle that no longer is in service is being converted into a drone response vehicle. It will provide space for all drone-related equipment to be ready to respond to an incident.

RFD’s drone response covers all of Wayne County, IN, and some portions of neighboring counties, should an agency need drone assistance on an incident.

Training and experimenting with the drones have shown that placards on railcars can be seen clearly from a distance of one-half mile away. This allows for safe identification of products that are in rail cars and highway transportation vehicles without putting personnel in harm’s way.

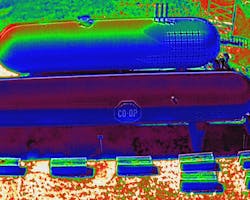

Via infrared camera, liquid levels in ammonia and propane tanks can be determined by reading the temperature of the liquid. At one incident to which the RFD responded, thermal changes were observed in the propane tank, but the liquid that’s in ammonia tanks is more difficult to observe. The department is looking to purchase an upgraded infrared camera to provide better images of the liquid levels in the tanks.

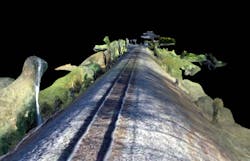

The RFD obtained software to enhance the capability of the information and photographs that are obtained from its drones. For both on-scene hazmat and fires, programs can be used to determine distances from drone photographs and elevation changes that are present at an incident site. Software is available for 2D and 3D. Currently, the RFD uses Pix4Dmapper, Pix4Dcloud and Pix4Dcatch, which is a comprehensive offline and online suite for photogrammetry. Photogrammetry entails the utilization of photography in surveying and mapping operations to measure the distances that are between objects.

The models that are produced via photogrammetry are used for looking at the aftermath of a fire or hazmat incident, rather than the live event, as well as measurements (distances, volumes, etc.). A site fly-through can be animated to provide comprehensive video of the incident, which is very useful in explaining a site and what happened during the response. The RFD can share models with police officers who investigate the causes of a fire.

The RFD helps with accident reconstruction using the 3D models, too: A drone will fly over a crash site before it’s cleared, which is much faster than manually taking photographs to make a record.

The RFD uses photogrammetry outputs for debriefings, enforcing city zoning laws, hazmat scene analysis, and reconstruction and fire investigations.

Pix4Dreact, which isn’t yet in use by the RFD, essentially is a fast-mapping software for emergency responders that provides 2D orthomosaics that can be created and used on scene quickly. (An orthomosaic map is an aerial photograph that’s geometrically corrected, such that the scale is uniform; in other words, the photograph has the same lack of distortion as a map.)

Because orthomosaics work in 2D rather than 3D, it’s much faster at processing, so results can be available in minutes compared with a 3D model, which can take much longer. The orthomosaics can be measured and annotated, so users can spot issues (i.e., damaged building structures) and can measure distances (i.e., between the fire engine and the entry point and between hazmat containers and scenes).

The speed of the software means that it can be used in live fires and hazmat incidents as part of an information-gathering effort. However, the drone that collects the imagery shouldn’t fly into the fire or visible hazmat releases, for obvious reasons. A drone can be used after an event, too, for a quick 2D model or for assessing damage, as it was used in the aftermath of the California wildfires in 2020.