On Feb. 20, 2003, the nation's fourth-deadliest nightclub fire occurred in the Town of West Warwick, RI, killing 100 people and injuring nearly 300. The emotional impact on the responding firefighters continues. Many will not discuss the incident; some still receive medical care. Legal proceedings are ongoing. Current and former officials from several fire departments, including West Warwick's, declined to comment for this article. Their decisions and their rights to privacy are respected. In deference to them, names are not published.

This article is prepared from police reports, evidentiary material released by the Rhode Island State Attorney General (RISAG), communications with several mutual aid responders, Rhode Island Department of Health library reference material, published media articles (especially investigative reporting by the Providence Journal) and two major technical reports — The Station Club Fire After-Action Report, October 2004, by the Office of Domestic Preparedness of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the June 2005 Final Report of the National Construction Safety Team Investigation by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), U.S. Department of Commerce.

Educational and technical dissertations have been published, seminars given and books written. Most quote the NIST and DHS reports. Both reports reference the Providence Journal. Those compiling reports during civil and criminal litigation had limited access to evidence and interviews. The fire chief was the only West Warwick firefighter allowed to be interviewed for the NIST and DHS reports. The professional association representing West Warwick firefighters was offered the opportunity to comment for this article, but declined to respond. Subject matter including inspections, codes, civil and criminal litigation, opinions and recommendations of published reports, violations, blame, culpability and liability are not covered. The scene firefighters faced is addressed. How they mitigated it is a learning experience for the fire service.

(Note: Times are listed two ways to match video recordings and emergency dispatch records.)

A program from a 2005 hospital safety seminar about The Station fire noted that no amount of training could have prepared the fire department for what it encountered. Smoke and flames poured from the structure with occupants fleeing from doors and windows; most burned — some were on fire. Hundreds of people filled the parking lot and streets; half were injured, many seriously. Some were lying on the ground, inside vehicles, in pickup truck beds and seeking relief from burns in snow banks. And conditions were rapidly deteriorating.

On Location

Scanning side A at 11:13:12 P.M., the WPRI video recorded flames visible outside atrium windows reflected in the tour bus windows. At 11:13:21, Engine 4 is filmed parked on side A. At 2313 hours, Ladder 1 staging on Kulas Avenue requested the fire alarm (FA) office to expedite rescues for serious burn victims (on side B). FA confirmed five out-of-town rescues had already been requested. The initial attack was in direct support of rescue efforts. Engine 4, Engine 1 and Ladder 1 personnel advanced handlines to the front entryway where trapped occupants were being subjected to flame impingement. An off-duty career firefighter from a neighboring city assisted in stretching hose.

In 13 seconds, the video shows flames extending eight to 10 feet out the entryway as a line is stretched — through fleeing occupants, over injured persons on the ground and around parked cars and the tour bus. Nine seconds later, flames were out all front windows. One video shows a burning patron exiting a barroom window as firefighters approached. The Rhode Island State Police (RISP) report confirmed that when Engine 4 arrived, multiple victims were trapped on top of one another in the front door. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) report had fire through the roof within five minutes of ignition.

Battalion 1, arriving at 2314, established Command on Cowesett Road opposite the A/D corner, and reported the building was well involved and that multiple rescues would be needed. He directed FA to have Engine 3 lay-in, have Engine 1 come straight in, start calling back off-duty members and specifically requested 12 additional rescues. Rescue 1 cleared its run and responded at 2314. A Warwick Police report logged its first officer arriving at 2314 and being approached by severely burned survivors. A Cowesett Inn restaurant (CIR) employee informed him a victim was already inside the restaurant. The officer directed other victims toward the restaurant, which by default became the main triage center.

When one Warwick police sergeant, a trained fire investigator, approached the fire building, he stated it was fully involved; heavy black smoke and flames were coming from various points; screams could be heard from people trapped inside, and firefighters were pulling people from the fire and making suppression efforts. A 2315 radio transmission from Engine 4 confirmed occupants inside the building. Engine 3 was blocked by traffic and Engine 2 laid dual 300-foot supply lines from a hydrant on Cowesett Road, pulling in close to Engine 4. It supplied a feeder liner to Engine 4 and operated its deck gun on the front entrance. Engine 3 started triage at the CIR. Between 2316 and 2317, command advised FA triage was being set up and staging for out-of-town rescues would be at the CIR parking lot. At approximately 2318, command requested another task force (equal to a third alarm). It is not recorded which companies filled this assignment.

Patrons self-evacuated and were assisted out by police and surviving patrons prior to Engine 4's arrival. The Providence Journal identified by name 247 people who self-evacuated — 90 via the side-A front doors, 46 via the side-B bar door, 12 via the side-B kitchen door and 20 through the side-D stage door. Via side-A windows, 25 exited the sunroom and 54 exited the barroom. Accepting the 2007 figure of 462 occupants and knowing 96 bodies were recovered, it is probable more than 100 people were rescued by firefighters before the building became completely untenable. The figure concurs with the 2003 fire chief's estimate of 100 people rescued, mostly through side A.

Mutual Aid

Hopkins Hill Rescue 6, positioning at the A/D corner on Cowesett Road, was surrounded by burn victims seeking assistance. The congregating injured created another triage area by default. Victims were evaluated and transported from there until triage was consolidated at the CIR. While responding, Warwick Fire Department (WFD) Battalion 1 directed his FA to start commercial ambulances and send the WFD recruit bus. WFD Engine 5, Engine 9, Rescue 4 and Battalion 1 arrived almost simultaneously at 2319. WFD Battalion 1, parking at the CIR, was confronted by injured seeking help. Ambulatory injured already heading to the restaurant reaffirmed it the logical location for triage and all EMS was directed there.

When WFD Battalion 1 reported to the command post, the INTERCITY — a common radio frequency used to communicate between regional control centers (RCCs), agencies and apparatus — was becoming overloaded. Both departments' apparatus remained on their respective frequencies with both chiefs operating jointly at the command post. WFD Engine 5 and Rescue 4 were ordered into the CIR to assist with EMS; Rescue 4 reported 50 to 60 injured inside. WFD Rescue 1, monitoring radio traffic and knowing it was shift change at Kent County Hospital, had FA notify Kent of the situation; hence, the hospital was double staffed. WFD Engine 9 assisted moving scores of victims in the streets.

On Cowesett Road, WFD Tower Ladder 1 was approached by many injured and the officer led them to triage. WFD Engine 1, ordered to the B side, laid a 300-foot, large-diameter supply line and directed its deck gun toward the front-door area from an elevated position on Kulas Avenue. The crew observed fire already through the roof and also was confronted by injured victims seeking medical assistance. Several handlines were advanced to side B and on burning gasoline under multiple vehicles ignited at the A/B corner. Via the INTERCITY, West Warwick requested three rescues from Cranston FA, which dispatched Rescues 2, 3 and 4 at 2321. Cranston Engine 4 and Ladder 2 responded as fill-in companies. WFD Special Hazards assisted crews working on side A. After the tour bus was removed, the Warwick tower ladder backed into the A-side parking lot adjacent to the West Warwick engines. Cranston Engine 4 rerouted to the scene, laying a four-inch supply line for the tower's elevated master stream.

Additional Resources

West Warwick's fire chief (Chief 1) called enroute at 2322, directing FA to implement the state's Mass-Casualty Incident (MCI) Plan through the Metro Control Center (Cranston's FA). This author could not access the 2003 plan components nor verify its effectiveness. An MCI trailer did respond from the state airport. At 2323, Rescue 1 notified FA that 10 victims were being transported, with five in critical condition; four rescues were on scene; at least 10 more were needed and they had 50 to 75 injured. A Warwick police officer, observing medical supplies dwindling, directed "gun trauma kits" retrieved from patrol cars. Command requested a commercial bus to transport ambulatory injured at 2326.

Arriving at 2324, Chief 1 ordered another call-back of off-duty members. The DHS report stated a cascading telephone call-back system was used. Also, off-duty members monitoring personal scanners began returning. Radio transmissions show West Warwick's Special Hazards, Rescue 2, Reserve Rescue 3, and Reserve Engines 5 and 7 responded. Off-duty dispatchers and the FA supervisor augmented the dispatcher on duty. Neighboring FAs monitoring fireground communications notified their off-duty command and EMS supervisory staffs. Many responded to the scene. Both NIST and DHS reports noted out-of-town chiefs and EMS supervisory personnel assisted the incident commander at the command post, acting as a resource group, serving as inter-agency liaisons and supporting functions such as communications, triage, supplies, staging, rehabilitation and public information. Chief 1 assigned two safety officers, one each from Warwick and West Warwick. Warwick supplied the rapid intervention team.

Within two minutes of Chief 1's arrival, Engine 1 and Ladder 1 reported the front entryway clogged with about 20 victims. Chief 1 requested all available manpower to the front and requested an additional 15 rescues. By 2330, three handlines and master streams from Engines 2 and 4 were in service on side A. At 2336, FA was advised live wires were down on side B. At approximately 2340, what remained of the barroom roof either burned off or collapsed. Command called for an accountability roll call. A partial collapse of the side A wall at the sunroom windows at 0015 hours initiated a second accountability roll call.

Four engines and one tower ladder operating three deck guns, one ladder pipe and numerous 1¾-inch handlines were used in suppression operations. The DHS report stated the equivalent of a four-alarm structural assignment responded to the scene, for West Warwick station coverage and manpower relief. INTERCITY radio traffic confirmed Metro Control requesting fill-in companies from Coventry and East Greenwich; departments designated by the mutual aid box system to move up on the third and fourth alarms. Due to the inaccessibility of records, no attempt will be made to list each responding apparatus.

The Providence Journal published a list of participating agencies from Rhode Island and southern Massachusetts, with a partial list of responding units. That list, the reports, and telephone and radio recordings indicate at least 22 engines, eight ladders, three special hazards, two squads and 57 rescues were involved. Commercial companies and independent ambulance corps provided another 15 to 20 ambulances.

Multiple fireground and INTERCITY radio transmissions requesting all available rescues and all available manpower may have resulted in assets self-deploying. Some agencies radioed both West Warwick and Metro Control on the INTERCITY to offer assistance. INTERCITY traffic was continuous and frequently overlapping. Some communications between RCCs and agencies were made by landline. Additional resources were also requested from the scene by out-of-town chiefs via their respective proprietary frequencies and cellular phones. The DHS report Annex A — Fire Department Operations acknowledged maintaining accountability on scene and determining what local resources were still available was challenging.

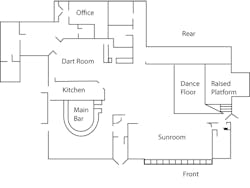

The DHS report stated the bulk of the fire was knocked down with the scene changing from a rescue to a recovery operation within 40 minutes. At 2337, command radioed triage that people were still being pulled out from side A. Although master streams are not normally used in occupied structures, firefighters credited their use on side A with saving lives where numerous occupants were trapped and simultaneous rescue-recovery operations were ongoing. Firefighters had to remove deceased victims to access survivors wedged in doors and hallways. A diagram released by the RISAG in 2004 with approximate locations of bodies showed 68 at or near side A. Thirty-one were inside the hallway and vestibule, nine at the dance-floor entrance to the vestibule, three in the main bar and 25 in the sunroom adjacent to the common vestibule and hallway wall and windows. Twenty-eight were dispersed in the B/C areas, which lacked exterior doors and windows.

Triage Areas

Two distinct triage areas emerged, one with Hopkins Hill Rescue 6 at the A/D corner and one at the CIR opposite the A/B corner. Twelve minutes into the incident, at 2325, triage was consolidated when Engine 1 radioed command confirming triage was inside the CIR. Several times, command directed FA to notify responding units of triage, rescue staging locations and specific travel routes to take.

As resources arrived, an Engine 3 member with a Cranston EMS officer conducted primary triage outside the CIR — tagging "red" critically injured for transport on the next-available rescue — and moving less seriously injured people inside for further assessment. Inside, an Engine 2 member with a Warwick EMS officer coordinated triaging victims — separating and tagging them "green" and "yellow" for treatment. As operations slowed, a sweep ordered of the fireground and surrounding areas found additional injured victims. At 0037, incoming rescues were canceled; all living victims had been transported. The DHS report Annex B — Emergency Medical Services noted the effectiveness of the EMS operation and in particular how out-of-town EMS supervisory staff and command officers assisted the triage and transport process. Within 90 minutes, about 200 injured were triaged and transported, mostly by fire department rescues and commercial ambulances; the balance in commercial and fire department buses and private vehicles.

Survivors' injuries and autopsy results can reveal accurate scientific representations of conditions inside a burning structure. Hospitals reported 273 patients treated, most with inhalation burns and smoke; 40%-plus with third-degree burns of face, upper extremities and upper body. An October 2003 Health Care Industry publication noted that 17% of 196 burn victims were admitted into intensive care on ventilatory support. Another stated that only four hospitalized victims expired, which was attributable to the airway-management skills of the EMTs and emergency physicians. A 2005 seminar estimated 20 to 30 critical third-degree burn victims were saved by firefighters.

The medical examiner's 2003 grand jury testimony, released in 2007, revealed autopsy results for 98 victims. Each specified the main cause of death listing any significant factors the medical examiner felt were contributory, noting the victim possibly could have expired without suffering the contributing factor. Eighty-six causes of death were from the "inhalation of products of combustion and a super-heated oxygen-deficient atmosphere" (inhalation). All 86 listed significant thermal burns as a contributing factor. Three listed thermal burns and inhalation as the primary cause, three listed inhalation and compression injuries and two listed compression injuries only. Four listed thermal burns as the main cause. Only one deceased, with compression injuries only, did not suffer inhalation or burns. Survivors' injuries mirrored those of the deceased. Dental records were necessary in identifying 70% of the deceased. The medical examiner testified 20 deceased had significant levels of cyanide, indicative of inhaling an atmosphere containing hydrogen cyanide, a product of burning polyurethane. Most of those bodies were recovered near the stage and dance floor.

Recovery & Rehabilitation

The DHS report stated the medical examiner's office was overtaxed. Grand jury transcripts indicate the U.S. Public Health Service Disaster Mortuary Response Team (DMORT) was requested to assist. West Warwick firefighters not on the first-alarm assignment assisted with body recovery. An officer with three firefighters (or firefighters from surrounding departments who volunteered) worked in teams with the medical examiner, state fire marshal and law enforcement. After locating, tagging, photographing and removing a body, teams attended debriefing sessions. Due to the large number of deceased, teams made multiple recoveries. Fire department rescues assisted in transporting bodies. The Providence Fire Department detailed several companies to assist at the morgue in Providence.

Rhode Island's Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) team was activated around midnight. Chief 1 required all firefighters debriefed by a CISM team member prior to being released from duty. A designated CISM rehabilitation area was established inside the CIR with three rescue crews assigned to rehab. Several fire department chaplains assisted. All Rhode Island fire departments, chiefs and union leaders were contacted after the incident advising of the availability of support in the form of defusing and debriefing sessions. Chiefs from several departments made CISM participation mandatory. CISM team members visited fire stations and conducted separate debriefing sessions for firefighters' family members. Five firefighters were physically injured, the most serious being a broken ankle.

A Providence Journal article stated when one first responder approached three co-workers at the scene, he said they wore the "thousand-yard stare" of horror. The emotional and psychological impact and resulting post-traumatic stress of responding to this incident cannot be measured.

WILLIAM F. ADAMS is a past chief of the East Rochester, NY, Fire Department and a former fire apparatus sales representative. He has 40 years' experience in the volunteer fire service.