A backdraft involves deflagration or rapid combustion of hot pyrolysis products and flammable products of combustion upon mixing with air. Several conditions are necessary in order for a backdraft to occur within a compartment. The fire must have progressed into a ventilation-controlled state with a high concentration of pyrolysis products and flammable products of combustion. Oxygen concentration in the compartment is low, generally to the point where flaming combustion is limited. In addition, there must be sufficient temperature to ignite the fuel when mixed with air

This is the second of three articles dealing with the extreme fire behavior phenomena, flashover, backdraft, and smoke explosion. The first article used a case study involving the deaths of three firefighters to examine flashover. While flashover and backdraft are quite different phenomena, both involve rapid fire progress and are frequently confused when encountered on the fireground.

A backdraft involves deflagration (explosion) or rapid combustion of hot pyrolysis products and flammable products of combustion (such as carbon monoxide) upon mixing with air. Several conditions are necessary in order for a backdraft to occur within a compartment. The fire must have progressed into a ventilation-controlled state with a high concentration of pyrolysis products and flammable products of combustion. Oxygen concentration in the compartment is low, generally to the point where flaming combustion is limited. In addition, there must be sufficient temperature to ignite the fuel when mixed with air (Grimwood, Hartin, McDonough, & Raffel, 2005; Karlsson & Quintiere, 2000).

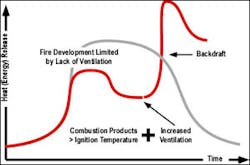

As illustrated in Figure 2, the energy release from a backdraft is extremely rapid and is generally transient, lasting only a short time. However, as illustrated in Figure 1, the fire often transitions to a fully developed state due to changes in ventilation resulting from the overpressure and heat release caused by the backdraft (Karlsson & Quintiere).

A Firefighters View Of Gas Laws

Gases and aerosols are fluids because they flow and to not have a definite shape. Gases and aerosols expand to fill the entire volume of their container. Understanding fluid dynamics (movement of gases and aerosols such as smoke) is important in understanding many aspects of fire development. However, this topic has particular importance in understanding how backdraft conditions develop and the way in which a backdraft occurs.

Charles Law: Gases expand in direct proportion to the absolute temperature (temperature in degrees Kelvin, Ko = Co + 273) applied to them. If the absolute temperature of a given quantity of gas is doubled its volume will double.

Gay-Lussac's Law: When the volume of a gas remains the same and temperature is increased, pressure increases in proportion to the absolute temperature of the gas.

Key Points for Firefighters:

- Gases expand when heated

- Gases become less dense and will rise when heated

- When gases are confined and heated, pressure increases

- Increased pressure indicates higher temperatures

When a fire develops in compartment, smoke rises to the ceiling and spreads horizontally through the compartment. Increased temperature reduces gas density. Less dense gases will rise. The difference in density between hot smoke and cooler air below causes them to separate into two distinct layers. The boundary between these two layers called the neutral plane. This is because the hot gas layer is trying to expand (Charles Law), but if it cannot, pressure will rise (Gay-Lussac's Law). Fluid pressure is exerted in all directions in an attempt to reach equilibrium.

Gravity Current and Air Track

The gas laws outlined in the preceding section provide a foundation for understanding why smoke moves the way that it does under fire conditions. However, there is another piece to the puzzle. Ventilation under fire conditions involves both smoke and fresh air. In general the smoke is hot and fresh air is cooler. What impact does this have? In fluid dynamics, the term gravity current is is used to describe a primarily horizontal flow in a gravitational field that is driven by a density difference. Air track describes the movement of smoke and fresh air in a compartment fire. Air track is influenced by both pressure caused by heating of gases and the difference in density between hot smoke and cooler air as illustrated in Figure 3.

Smoke and air mix along the boundary of the gravity current. If the concentration of the smoke (fuel) air mixture reaches the flammable range and is above its ignition temperature it will auto ignite, resulting in a backdraft. The volume of smoke that is within its flammable range and the extent to which it is confined are major factors influencing the violence of this combustion reaction.

Case Study Method

In the previous article Extreme Fire Behavior - Flashover, the case study method was presented as an excellent approach for developing your knowledge and understanding of fire behavior. Just to review how to approach a case study: Read the questions to be answered first, this provides you with a framework for understanding the information presented. Second, read the case to get an overall understanding of the incident. Last, examine the incident in detail to answer the questions posed at the start of the case. When using case studies as an element of fire behavior training, the following questions serve as a good starting point for your analysis:

- Was extreme fire behavior involved in this incident? If so, what type of event happened?

- How did the fire develop and what factors influenced the occurrence of the extreme fire behavior phenomenon?

- What clues were present that may have indicated potential for rapid fire development?

- Compare and contrast these the case studies with other cases or events in your own experience. What aspects of these incidents were similar? Which were different?

In addressing the first two questions, what happened and what were the contributing factors it might be useful to examine the fire development curve presented in Fire Development in a Compartment. What stage (incipient, growth, fully developed, or decay) and what burning regime (fuel controlled or ventilation controlled) is the fire in immediately prior to changes in fire behavior. Additional questions can focus on incident specific issues such as the effectiveness of tactical operations.

Case Study

This incident involved an early morning fire in a two-story, mid-terraced house (townhouse). This fire resulted in the deaths of a child and two firefighters in Blaina, Gwent, in Wales (UK). Data for this case was obtained from the Fatal Accident Investigation report conducted by the British Fire Brigade Union (FBU, 1996) and analysis of the incident by Paul Grimwood (1998; personal communication February, 2006). In that this case is situated outside the United States, a brief explanation of deployment, resources, and tactics is likely in order. This area of Wales is served by retained duty (paid on call) firefighters operating from several fire stations each with a pump (engine company). Staffing varies, but on the morning of the incident the first arriving company, pump B031 (Blaina Station 3, Engine 1) was staffed with a sub-officer (Lieutenant), apparatus operator, and four firefighters. In the UK tactical operations are not unlike those used in the US (fire attack, primary search, etc.). However, 19 mm (3/4") and 25 mm (1") hosereels (booster lines) are commonly used for initial attack on contents fires. While deployment and tactical differences are interesting and a great starting point for discussion, don't be distracted from the significant fire behavior lessons presented by this incident.

Construction: The house was built on a concrete slab with concrete block walls with brick veneer on Sides A and C. A concrete block wall also separated the stairwell from the living room and the kitchen from the living room. The second floor was supported by a mix of 75 mm x 175 mm (3" x 7") and 50 mm x 150 mm (2" x 7") joists with weyroc (tongue and groove particleboard) flooring (thickness not specified). All other internal partitions were fabricated with 50 mm x 100 mm (2" x 4") studs. Interior finish was plasterboard (unspecified thickness). The ceiling had a skim coat of Artex (textured plaster). Windows on floors one and two were 780 mm x 870 mm (36.7" x 34.25") and constructed of unplasticised polyvinyl chloride (UPVC) and glass. Interior doors were lightweight wood with "egg crate" internal separation.

Configuration: The unit involved in the fire had a kitchen and living room on floor one and two bedrooms, bathroom (sink and shower) and water closet (toilet) on floor two. Figure 4 shows a plot plan and plan view of the first and second floor of the involved unit.

Fuel Profile: Contents were typical of a residential structure and included ordinary kitchen, and living room furniture. The fire originated in clothing located in the kitchen. In addition, all rooms were carpeted. Research conducted by the British Fire College Fire Experimental Unit (FEU) indicated that carpet can contribute significantly to fire load and can have a significant impact on fire development and intensity. This finding is independently supported by research conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) examining fire development in the deaths of two firefighters during a training exercise in Osceola, Florida in 2002 (Hollenbach, 2002).

Ventilation Profile: At the time of ignition there were not ventilation openings to the exterior of the structure and the door between the kitchen and living room was open. The occupant discovered the fire at approximately 0548 and reportedly closed the door between the kitchen and living room and exited the structure, leaving the front door open. At approximately 0605 (five minutes prior to the arrival of the first company) the kitchen window failed (at least partially) with flames exiting the widow. Smoke pushing from the front door raises the possibility that a gravity current had developed at this opening as well as at the kitchen window (See Figure 4).

The FBU investigative report indicates that the fire breached the ceiling/floor between the kitchen and bedroom two (See Figure 4) at 0615, changing the ventilation profile and related air track. However, subsequent analysis (Grimwood, 2002; personal communication P. Grimwood, Febrary 2006) indicates that the ceiling/floor may not have failed until later in the incident.

Fire Development: The fire originated clothing located in the kitchen (See Figure 4). The exact time of ignition is estimated at 0537. The speed with which the fire may have progressed from incipient to growth stages is unknown. However, the occupant discovered the fire at approximately 0548 and was able to close (partially?) the door between the kitchen and living room prior to escape. This indicates that the fire had not yet reached flashover. Sufficient heat was developed within the kitchen to cause failure of the kitchen window. This could have occurred fairly early in fire growth, as the melting temperature of CPVC can be as low as 150o C (302o F). This provided an additional, but limited supply of air to support fire growth to flashover within the kitchen. Dr. Martin Thomas of the FEU estimated that post flashover ceiling temperatures in the kitchen were as high as 1000o C (1832o F).

Flaming combustion was not observed from the doorway on Side A at the time firefighters entered the structure. However, it is possible that combustion was occurring above the neutral plane and the dense smoke obscured it from the firefighters view. Shortly after 0615 (five minutes after arrival of the first company) there was a deflagration resulting in an immediate transition to flaming combustion on both floors one and two.

Initial Tactical Operations: Initial response to this incident was a single pump (six personnel) and Station Officer. Upon receipt of additional information that there were persons reported in the building, a second pump (five personnel) was added to the incident. As the first company (B031) arrived on scene, they observed thick, dense smoke from the house drifting across the road. Initial size-up showed a large volume of black smoke from the open front door as well as smoke showing from the eaves. The windows on Side A were intact and showed evidence of condensed smoke (staining of the window glazing). It was apparent that both floors one and two were smoke logged (substantial smoke accumulation within the compartments on each floor).

Bystanders reported that there were children in an upstairs bedroom. Initial tactical operations involved primary search by on floor two, by two firefighters with a hosereel (