Critical Boston Apparatus Maintenance Report Can Serve as Learning Tool to Fire Departments

Read Full Report

Apparatus Architects: The Boston Report

The Jan. 9 tragedy in the Mission Hill neighborhood of Boston that took the life of 30-year veteran Lt. Kevin M. Kelley shook the department and put its apparatus maintenance division under a microscope.

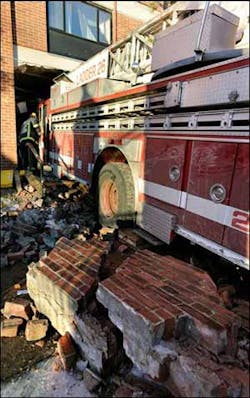

That afternoon, Ladder 26 careered down a steep hill and crashed into a high-rise apartment building, wedging the truck into it for hours following the crash. Kelley was sitting in the front passenger seat and died instantly.

A preliminary investigation of the crash found catastrophic brake failure was to blame, and the department's maintenance division was soon scrutinized for inadequacies that were highlighted in a report commissioned by the city and released on March 6.

Larry Stewart, NFPA's staff liaison to the Automotive Apparatus Committee, said that these incidents, while tragic, ultimately educate members of the fire service and draw attention to the importance of following accepted standards of operation.

"Every time someone gets hurt or killed, we walk away with a piece of knowledge of how we can learn from the incident," he said.

The report -- created by Maryland-based consulting firm Mercury Associates -- found there was no professional fleet manager or maintenance technicians, roles of Boston's maintenance division members were not clearly defined, there was no effective vehicle inspection program and the division lacked a sense of ownership and responsibility for the apparatus.

"Even 15 to 20 years ago I would question how effective (their practices) would have been," Paul Lauria, president of Mercury Associates, said. "I think it makes perfect sense for some routine inspections to be done in the firehouse, but maintenance is different."

When asked whether large departments such as Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco -- all of which he has done consulting work for -- employ practices that resemble those adopted by Boston, Lauria put it bluntly.

"(Boston) was the exception," he said. "Not doing these things is way behind the times; I don't think it takes an expert to understand that."

The lack of civilian mechanics was a key point highlighted in the report which stated the department had employed them at one time, but that those positions had since been eliminated for budget reasons.

Following the release of the findings, media outlets reported that Boston Fire Commissioner Roderick J. Fraser vowed to replace the current maintenance division with civilian mechanics.

"A fire department's main mission is to fight fires, not to manage a fleet," Lauria said.

"When you look at the nature of the beast ... it's a mission in which it's inherently difficult to remain vigilant all of the time. It's really difficult when you don't know when (apparatus) is going to be used next and for what."

While departments should follow NFPA standard 1911 -- which defines minimum requirements and sets guidelines for apparatus maintenance -- practices vary from city to city, Lauria said.

Lauria said that while most departments have a decentralized maintenance division, cities such as Seattle and San Antonio have centralized their fleet management.

The preference, he said, is not to see apparatus maintenance as part of Public Works, since many departments are reluctant to allow the city to take control of the maintenance of its vehicles. He said that there are plenty municipalities that do have centralized fleet management and do it well, but that it depends on how the city handles the arrangement.

He said practices depend on the way a municipality manages them, the adequacy or resources and the management of money.

"A mistaken belief that if (a municipality) cuts funds for vehicle replacement, they'll save money, but in actuality they are moving costs to a future year," he said. "Costs don't go down in time; they go up."

He said that at the end of the day, any fire department's approach to fleet management comes down to the leadership of the chief.

Lauria was hesitant to say if he believed the Boston report would necessarily spur improvements in fire apparatus maintenance nationwide, but tied to be optimistic.

"I hope some elected officials and mayors out there look at this (incident) and take a look at this report," he said. "I think that anything that causes people to stop and ask questions is a good thing."

Stewart said that departments should follow NFPA 1500, the standard on fire department occupational safety and health, as a guide and points to standards such as 1911 and 1901 -- Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus.

"I think a lot of the fire departments in spirit try to comply with 1500, but it is tough to point out one that follows everything in it," Stewart said.

NFPA's standards are voluntary compliance, unless a given jurisdiction decides to adopt a standard into law. Because of this, it is difficult for the NFPA to keep track of what departments follow their standards.

The only time the organization finds about a department not following a standard is when an incident -- such as what happen with Ladder 26 -- occurs.

Related Links:

Related Stories:

- Boston Lagging in Apparatus Driver Training

- Following Report, Boston Fire Commissioner Wants to Hire Civilian Mechanics

- Report: Boston Gets 'F' for Fire Truck Maintenance

- Brakes Failed in Boston Fire Truck Crash

- Boston Fire Truck Driver Clean in Fatal Wreck

- Boston Pulls 3 More Vehicles Out of Service

- Fallen Boston Firefighter Laid to Rest

- Another Boston Ladder Truck Pulled from Service

- Truck in Fatal Boston Crash was 'Fit for Service'

- Malfunctioning Boston Truck Crashes into Car

- Inquiry Board Will Probe Boston Crash

- Boston Lieutenant Killed After Ladder Truck Smashes into High-Rise Building