Retracing the Last Fatal Steps in a Young Firefighter's Life

Members of the "inside team" of Ladder Company 36, a lieutenant and two junior firefighters, had to get out of the burning building in upper Manhattan. They retreated, groping, through the second floor, stumbling to a stairwell filled with a crush of other escaping firefighters.

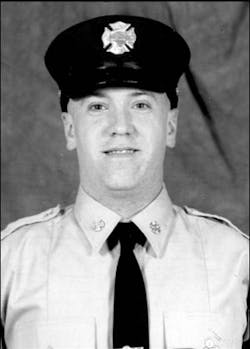

There, the lieutenant did a quick check, peering at the two masked firefighters who had followed him out. "Brick?" he asked one, believing the man to be 30-year-old Firefighter Thomas C. Brick.

"He said, `Brick? Are you Brick?' Somebody said, `Yeah, I'm Brick,' but he still had his mask on," a fire official familiar with the conversation said yesterday.

It was a case of mistaken identity in the blanketing smoke and suffocating heat, caused by the confusion of either the man who asked the question or the man who answered it. It was not Firefighter Brick, a man on the job for just over two years. It was a firefighter from another unit, several fire officials said yesterday.

Firefighter Brick, the father of young children, was still trapped inside.

When the error was discovered, it was too late. A special rescue unit found him unconscious on the floor, his air mask off, his face black. He was taken to Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center but soon became the first firefighter to die fighting a blaze since Sept. 11, 2001.

The events of Tuesday afternoon in a burning two-story building on 10th Avenue in Inwood were a reminder that the smallest misstep can have far-reaching and deadly consequences. In some cases, a hose a fraction of an inch too small or a kink in a line have led to firefighters' deaths. In this case, the cause may have been a case of mistaken identity that hinged on a nod of the head.

Yesterday, as the Fire Department began a standard inquiry into the death, questions were being raised, some of which focused on how the order to pull out of the building was relayed, and on the lieutenant's accounting of his men. Firefighter Brick's equipment was also being checked for faults. Some veterans asked whether inexperience contributed to the death.

Firefighter Brick was one of the many newcomers who have flooded the department since Sept. 11. The lieutenant, whose name was not released, has been with the department for eight years but became an officer only a year ago.

An officer can order firefighters out of a building in various ways, a department official said yesterday, including a pat on the back, a verbal order, or a radio call. While there is no strict procedure, the official said, he acknowledged that the group should stick close together. Department veterans said commanders usually keep their teams close enough to be in voice contact.

Firefighter Brick, though, was separated from the rest of the group by a cloud of dense smoke, Fire Commissioner Nicholas Scoppetta said yesterday. He did not radio a mayday, or press an emergency call button on his radio. Although he was badly burned, the medical examiner said yesterday that he had died of smoke inhalation.

After it was learned that the man the lieutenant thought was Firefighter Brick was actually someone else, the roll was called at the scene, officials said. It was unclear whether the rescue unit was dispatched before the roll call was completed, or whether precious minutes passed, officials said. The rescue team found the body 10 minutes after entering the building.

The sequence of events is crucial to the department's inquiry into what went wrong.

Typically, a ladder officer