The Rebirth of the Rapid Ascent Team: Part 1

Author's note: Immediately after 9/11, I created a tactical concept in high-rise firefighting called a Rapid Ascent Team. Initially, it was based on the obvious physical and tactical strain on firefighters having to rapidly ascend to upper floors of tall buildings to effect rescues and guide people to safety. In recent times, serious high-rise fires have occurred in North America and abroad in which civilians perished on floors well above the fire. Within one five-year period, 17 civilians died in fires in Chicago, New York City and Toronto; the victims shared one common fate with three primary factors — they were found in the attack stair, they were well above the fire floor and all died of carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning. It was after a 2003 fatal fire in a Chicago office tower where six civilians died in an attack stair 10 floors above the fire where I believe it came to light that the fire service must finally address this recurring calamity — people keep dying in our attack stair. I met with their commissioner at the time, Cortez Trotter, and recommended its adoption. He agreed it had solid merit. It was written into their standard operating procedures (SOPs) and the Rapid Ascent Team was officially transitioned from concept to reality. Very soon thereafter, it would be put to the test in another major high-rise fire. Although it took a while to get the fire service as a whole to embrace the idea of Rapid Ascent Teams, it has now firmly taken hold. Now, many cities have adopted the idea of Rapid Ascent Teams in various forms, making it part of their high-rise SOPs.

What is a Rapid Ascent Team? Reviewing the idea's conception, it consisted of specific teams of firefighters whose sole responsibility during a serious high-rise fire was to quickly get above the fire floor and perform two essential functions that greatly and directly impact the overall outcome of the event:

- Performing reconnaissance for the command post by providing concise, accurate intelligence regarding conditions on upper floors and what additional resources will be required to achieve key objectives noted while carrying out their assignment (i.e., fleeing tenants reporting co-workers missing on particular floors and relaying this assignment to search crews soon to follow).

- Informing evacuees as to what they should do and where they should go for safe refuge. This may involve a "defend-in-place" posture in minor fires or a full-scale evacuation of all upper floors in the worst of events.

Most importantly, these teams directly intercept the building evacuees during their response mechanisms and advise them to leave the stairwell the department has chosen to attack the fire from (known as the "attack stair"), which has proven to be a deadly place for civilians. The teams direct the populace to transfer over to the opposite stair in a standard two-core stairwell configuration that would be designated as the "evacuation/search and rescue stair." This decision would be channeled from the command post directly to the occupants via the public address system and Rapid Ascent Teams after the attack team has announced its chosen attack stair. Building occupants in most cities know nothing about the "attack stair" and the inherent dangers of being in the area where fire byproducts likely will enter, thus contaminating the shaft and turning it into a chimney of toxic gases. Since the majority of deaths occur due to CO exposure and the fact it is odorless, colorless and tasteless, they are mostly clueless as to the dangers of this gas commonly referred to as the "silent killer."

Other gases from burning natural materials and synthetic compounds, such as hydrogen cyanide, hydrogen chloride and vinyl chloride, can add to the deadly threat of exposure to fleeing occupants. The two predominant gases that kill most people are CO and hydrogen cyanide. Most civilians do not understand that the exit stairs are typically a safe area of refuge — until the fire attack commences. Then their path of egress can become a bad location for them to be if they are in the stair above the fire where a hoseline is being advanced onto the fire floor. (An exception would be a hot-weather fire with a significant "reverse stack effect," or downdraft, taking place, whereby air and smoke are pulled downward via shaftways.) The door must be propped open during this procedure to prevent it from closing on the hose. Without good stair pressurization keeping the bulk of toxic gases from entering the shaft, contamination is likely to occur. Attaching the attack and backup lines out on the fire floor to prevent this from occurring is not a safe, viable option.

Tracking CO

I recently added one more key duty to the Rapid Ascent Team assignment and that is an extremely important concern for every competent fireground commander in a high-rise fire — knowing where the major concentrations or pockets of CO reside within the tower. Contrary to popular opinion, CO is only slightly lighter than air. In its purest form, it is only 3% lighter than air. Still, except in cases of "reverse stack effect," CO rises in stairwells, elevators and other shafts, which has resulted in multiple-fatality incidents remote from the fire area. Why does this occur? Simply, it is the heat convection from the fire in combination with the natural stack effect of the building itself that brings this about. Early into the fire, the vast majority of SOPs dictate that a range of three (minimum) to five (maximum) floors of "stair runs" above the fire must be searched for occupants who are evacuating down the attack stair. In addition, many big-city SOPs also mention that the upper floors at and around roof level in this stair must be checked for smoke migration and contamination early into the fire. Is this truly adequate?

Certainly, it can be argued that wherever the visible/particulate smoke is, the non-visible CO has to be in close proximity. However, in many circumstances, the CO never makes it to the top of the building, but instead will stratify in one or more pockets between the fire floor and the roof (and sometimes even below the fire floor in warm-weather fires). These pockets must be sought out, identified and reported back to the command post for tracking purposes, not unlike the tracking of fire crew locations and assignments.

CO readings should be taken by the Rapid Ascent Teams at five-floor intervals in tall buildings while they work the stairwells above the fire as they pause for rest. The reason this would be important to know is that if a "defend-in-place" operation is in effect and people are being advised to hold their positions on upper floors or are being directed back onto certain floors as they descend from the top of the building in a "re-entry and hold" posture, they may be placed in great danger. They may not even know CO is present, as it can indeed exist in areas where there is little to no carbon particulate matter present from the combustion process taking place many floors below.

(Note: Granted, in some instances, tenants working after hours who may be directed out of the attack stair onto certain unoccupied floors may not easily find the opposite stair to use for evacuation due to lights being off and confusing core layouts. In some cases, the other stair may not even be accessible due to secure tenant areas. A trailing search crew to the Rapid Ascent Teams may then have to be assigned to deliver groups of people over to the evacuation stair in such circumstances. The primary objective is for the Rapid Ascent Teams to confine their operations to the stairwells and not become bogged down or redirected onto floors to do searches or guide people to other stairwells.)

The Rapid Ascent Team concept now addresses three critical areas of concern for any incident commander:

- Directing people out of the attack stair and out of harm's way.

- Performing reconnaissance for the command post; to become the "eyes and ears" of the incident commander.

- Take CO readings at various intervals to determine where major pockets exist.

Of interest: The FDNY has CO detectors clipped to all chiefs' and company officers' radio straps that can be used in high-rise fires that show CO level. It reads 35–999 ppm (parts per million). It vibrates and emits an audible alarm at 35 ppm. Less expensive and less sophisticated CO detectors can be purchased that can easily clip onto fire gear of Rapid Ascent Team members that emit an alarm when a threshold limit of CO is reached that would also be effective for this application.

Equipping the Rapid Ascent Team

Is there a limit as to how high firefighters can climb? Realistically, most fire departments in cities with super-tall skyscrapers would be hard pressed to place teams above the 60th floor if they were forced to ascend from grade level (elevators out-of-service) due to the tools and equipment they carry and the weight of the gear they wear, which is not appropriate for hiking straight up 600 feet or more. Even firefighters in excellent physical shape would be stressed to their limits in vertical ascents of this magnitude in acceptable time frames. So, what must be done to lighten their burden? In addition to good conditioning, the gear they wear has to match the task at hand.

Ideally, pre-designated Rapid Ascent Team members would have lightweight turnout gear similar to what many California fire departments don when responding to brushfires. They would wear lightweight footwear (station-type boots), not thick, heavy and cumbersome rubber turnout boots that are not conducive to climbing small mountains. They would use 60-minute air cylinders (30- and 45-minute cylinders are not appropriate for this concept) and bring "irons," spare bottles and other standard small equipment such as lights, radios, spare batteries and small bullhorns. Extra bottles are a must; perhaps firefighters can improvise with the use of woven sleeves that slide over the self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) bottle, which has a pouch on either side that can hold a spare bottle (see photo on facing page). Placing the load on the back and freeing up one's hands is important. They could also consider removing their helmets and clipping them to their coats to release body heat escaping from the head area.

If elevators are active, the team members would take them to two floors below the fire and work their way up from there in a rapid ascent fashion. One team would soon be followed by another. It must be emphasized that before going above the fire, the Rapid Ascent Team members should note the location of the opposite stairwell in relation to the general core layout in case they run out of air and are forced to enter an upper floor in possible smoke conditions.

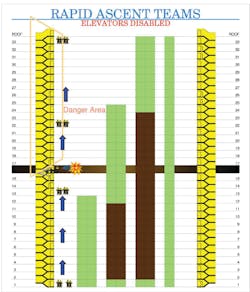

If an elevator bank passes the fire floor in a blind shaft, with no access hatches or doors penetrating the shaftway, Rapid Ascent Teams or standard search teams may use this resource to gain immediate access to the upper levels of the building (see Graphic 1). They could then quickly perform reconnaissance and begin a descent, putting far less strain on themselves. In doing so, however, great care must be taken, including running a full safety test of a chosen single car in that bank with one fire company/Rapid Ascent Team.

Safety from Exposure Issues

Ensure beforehand that the elevator machinery room has no exposure issues from heat or smoke. This can be done by communicating with lobby control that no alarms are activating on that floor deck and by checking the in-cab feature (if present) of a blinking fire helmet or Maltese cross on the panel, which would indicate trouble in the machinery room. If elevator service has been lost, then hiking stairs — contra-flow to evacuee traffic — must take place (see Graphic 2).

Lighter gear plus a higher degree of physical conditioning equal the greatest chance of the Rapid Ascent Teams' success in carrying out their important objectives on upper levels. The concept proved itself to be valid on a major high-rise fire in 2004 (LaSalle Bank Building Fire), when scores of people were rescued by the Chicago Fire Department's newly formed Rapid Ascent Teams. It was the first time the concept was applied in real fire conditions. The benefits of the idea were now clear — it can work.

Next: Expanding the role of the Rapid Ascent Team.

CURTIS S.D. MASSEY is president of Massey Enterprises Inc., the world's leading disaster-planning firm. Massey Disaster/Pre-Fire Plans protect the vast majority of the tallest and highest-profile buildings in North America. He also teaches an advanced course on High-Rise Fire Department Emergency Operations to major city fire departments throughout the U.S. and Canada. Massey also regularly writes articles regarding "new-age" technology that impacts firefighter safety.

About the Author

Curtis Massey

Curtis S.D. Massey is president of Massey Enterprises Inc., the world’s leading disaster planning firm. Massey Disaster/Pre-Fire Plans protect the vast majority of the tallest and highest-profile buildings in North America. He also teaches an advanced course on High-Rise Fire Department Emergency Operations to major city fire departments throughout the U.S. and Canada. Massey also regularly writes articles regarding "new age" technology that impacts firefighter safety.