Fast-Moving Wildland Fires Require a 'Box' Incident Command Strategy to Ensure Saving Lives Is the Priority

Key Takeaways

- Breaking a rapidly spreading wildland urban interface (WUI) fire into small parts allows incident commanders to direct crews to operate to save lives and protect property first, despite the latter’s inclination to conduct fire suppression efforts.

- WUI fires are best managed with divisions and groups under the operations section of the incident command system.

- It is advantageous to use natural fire barriers, such as roads and trails, and natural features that don’t burn, such as rock ridges, sand beaches, rivers and larger bodies of water, when drawing the box (i.e., containment boundary) around a WUI fire.

Fire season” might conjure images of crown fires jumping through canopies of Ponderosa pines in the Rockies or palm trees of Southern California desperately pointing toward the Pacific while Santa Ana winds scatter fist-sized embers from neighborhood to neighborhood. However, devastating wildfires now occur year-round from Maui to Maine, and wildland urban interface (WUI) fires are affecting communities in more significant ways than we ever saw. The newly anointed might be overwhelmed by the speed, scale and size of these fires.

Large WUI fires can’t be handled in the same way that an incident commander (IC) might handle a structure fire, considering that accountability and mapping are critical when neighborhoods are threatened. The savvy IC can enlist help in the command post and utilize new technologies that are designed particularly for incident command to enhance situational awareness and to quickly organize the incident. Breaking the fire into smaller parts and decentralizing command by placing bosses in each part of the incident allow for the incident to be more easily managed. By doing this, the IC can maintain a reasonable span of control and maintain accountability for the crews that operate in the hazard zone, particularly when protecting lives and property becomes the top priority.

Although the temptation might be to pour efforts into suppression, the IC, with the help of many eyes and ears, must determine whether structures immediately are threatened and, worse, whether citizens are trapped. When this is the case, the first-arriving resources must put all of their focus on evacuations and structure protection. Establishing control lines can happen later or be delegated to next-arriving officers.

ICS’s role

What’s the work flow for a rapidly scaling wildland incident from dispatch to deployment of resources when structures and lives imminently are threatened?

Recognition. Recognizing that a WUI fire in a particularly vulnerable area will cause major problems is an important first step in taming the beast. Also recognizing that you might need to dedicate initial resources to saving lives and property is critical. To accomplish this, you need large resource orders and a method of sorting them. Doing this early and often is key to a more successful outcome.

Respect the command post. A few years ago, I attended a high-rise class by then-Division Chief Tom Siragusa (Ret.) of the San Francisco Fire Department. He exclaimed to all of the students, “Respect the command post!” In other words, there’s a lot going on in big incidents. Get help.

During rapidly scaling WUI incidents, information pours into the command post via multiple sources, including panicked radio reports. Sorting and prioritizing this information is a huge challenge. At the very least, ICs can use a company officer and/or an additional chief officer to listen to radio traffic, drag and drop crews on a map or into a tactical worksheet, look at maps and review checklists.

ICS review

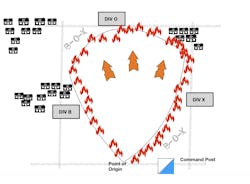

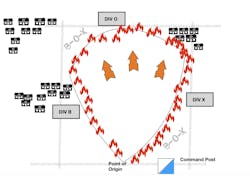

WUI fires are best managed with divisions and groups under the operations section of the incident command system (ICS). Divisions are set up in a clockwise manner and alphabetical in the horizontal plane, as in a WUI fire. Groups are assigned to a specific task and move fluidly through the incident; although they may work within a division and in coordination with the division supervisor, they generally don’t work for the division. Divisions and groups have the same rules about the need for a supervisor, accountability, communications plans and span of control.

Creating boxes

WUI fires can get very big very quickly, so how do you eat this elephant? One bite at a time.

This means slicing the incident into smaller, manageable portions, or divisions. Each portion is given to a supervisor. Each supervisor’s actions and decisions support the overall strategy and incident objectives. To achieve that, one must draw a box around the fire. This box may be drawn in dry-erase marker on a map, sketched on a white board or traced on a tablet-based incident command platform.

Boxing the fire has two components:

Drawing the box. When drawing the box (i.e., containment boundary), utilize natural fire barriers, such as roads and trails, and natural features that don’t burn, such as rock ridges, sandy beaches, rivers and larger bodies of water, to your advantage. As long as there are no lives and property between you and the fire, it’s OK to let the fire burn to you, where you hold and contain it within your box.

Incident command platforms, combined with Fire Mapper, can help ICs quickly get a satellite view of an area, to help to draw the box.

If the fire gets bigger because of natural conditions, draw a bigger box. It happens. Don’t panic.

Establish divisions on the fire. When considering the box, think of it as standing for Bravo, Oscar and X-ray. We typically try not to start with Alpha, because it doesn’t leave a lot of options if there’s a shift in conditions and the fire burns back toward us, and we must open another division to our left.

If the fire grows bigger, break it into even smaller bites and create additional divisions that are alphabetically sequential.

Group labels

These large fires behave by an entirely different set of rules, and rules of engagement change when the fires encroach on structures. As much as we might try to contain or hold the fire in our box and install divisions to secure a fire perimeter, we also might need to install groups that have the assignment of structure protection and evacuations.

When I make groups for structure protection, I label them with numbers. I used to label them by a street name or an area where they were protecting structures, but when fire blew past them, I had to rename the groups. This can cause confusion in an already-confusing environment. I now use the naming convention as follows: “Structure Protection Group 1,” “Structure Protection Group 2,” etc.

Way to clearly communicate

When assigning divisions and groups, TORC (Titles, Objectives, Resources, Communications) ensures that incident objectives and chains of command and communication are understood. It also is a solid way to maintain accountability in the early stages of an incident.

When I assign divisions, I make sure that the supervisors know without a doubt what their title is when I call them on the radio. I list their objectives and make sure that the supervisors understand them. I make sure that the supervisors know which resources currently are assigned to them or will be assigned. I ensure that we are clear on the communications plan.

An example of how I might assign a division is:

“Captain 381, you’re now Division Bravo.” (title)

“Hold the fire at Jones Road on the left flank and mobile attack the fire.” (objective)

“I’m assigning you Engine 382 and Engine 383 and another wildland engine when I get one, and they are working for you.” (resources)

“Command channel is Delta 1 and TAC is V-Fire 22.” (communications plan)

An example communication for a structure protection group supervisor is:

“Captain 109, I’m making you Structure Protection Group 1.” (title)

“Protect homes and/or evacuate citizens. Start at Mallard Court and advise on movements.”(objective)

“You will have Engine 103, Engine 104 and Engine 113 working for you.”(resources)

“Command channel is Delta 1 and TAC is V-Fire 22.”(communications plan)

Repetition

As WUI fires continue to ravage communities, most notably in areas that traditionally weren’t affected, it’s essential to adopt strategies that help to bring order to the chaos.

It’s critical to recognize when the incident is going big. That’s a trigger for you to go big, too. Order resources early and often and use the ICS to stay ahead of the incident. It also is critical to correctly identify priorities, such as structure protection and evacuations, because they might take precedence over direct fire suppression efforts.

Now, all of these theories are great in concept, but they will be completely ineffective without consistent training and real-world practice. These two things allow ICs and crews to build fluency in the ICS and allow responders to act with clarity and purpose under pressure. Repetition reinforces muscle memory, which makes complex decisions feel instinctive in high-stress environments, and sharpens recognition and primes decision-making.

Product Spotlight

Wildland Goggles

Built for the intense heat of wildland firefighting, the ESS Influx FirePro 1977 goggle offers superior protection against smoke, flying debris and embers. Its Adjustable Ventilation System (AVS) with RotoClip lets firefighters switch from sealed to open-vent mode instantly, to ensure clear vision, comfort and performance in the harshest, hottest conditions.

Wildfire Shields

Used by professional firefighters for more than 20 years, FireFoil is a high-performance structure wrap that protects buildings from wildfire heat and embers. It reflects more than 95 percent of radiant heat to help to prevent ignition and is ideal for rapid deployment in high-risk zones. The company’s new product line includes reusable shields and rolls from 500–2,000 sq. ft..

5-Gallon Fire Pump

Built for wildland fire crews, the Smokechaser Chief from Forestry Suppliers delivers reliable, on-the-go fire suppression for wildfire response, mop-up and prescribed burns. Its five-gallon nylon bag features a puncture-resistant liner and a wide, stable profile for comfort and mobility. A U.S. Fire Service-approved brass pump provides powerful, controlled spray with minimal effort.

Safety Goggles

The FireArmor Wildland LT300 safety goggles from HexArmor are certified to NFPA 1977: Standard on Protective Clothing and Equipment for Wildland Fire Fighting and Urban Interface Fire Fighting. The goggles’ advanced anti-fog technology, scratch resistance and enhanced ventilation are designed to revolutionize wildland fire protection and allow firefighters to defend their eyes with confidence and comfort.

Wildfire Barrier

The WFS net from INternational CArbide Technology (INCA) is an innovative system to get in total control of wildfires. The intumescent mesh withstands temperatures hotter than 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Further, the mission-critical WFS platform supports real-time wildfire response, offering a graphical representation that enables enhanced situational awareness by showing a real-time, intuitive map of the fire zone and surrounding operations.

About the Author

Andrew Bozzo

Andrew Bozzo is a battalion chief for the Contra Costa County Fire Protection District (Contra Costa Fire) in the San Francisco Bay Area. He has 27 years in the fire service. Bozzo started his career as a seasonal firefighter for CAL FIRE and then served in Washington state. He has served for the past 17 years at Contra Costa Fire, which, in 2007, suffered two line-of-duty deaths during a rescue attempt in a residential fire. From that tragedy was born Tablet Command, which Bozzo cofounded to help to introduce departments to enhanced and more accurate accountability and incident command systems.