New Orleans Fire Department Hazmat Response Following Katrina

News media personnel, emergency responders and others have said that you cannot appreciate the devastation in New Orleans from news footage and photos. What an understatement, as I learned when I visited New Orleans on Dec. 23, 2005, to talk with members of the New Orleans Fire Department Hazmat Team.

Under ordinary circumstances, a visit to the New Orleans hazmat team would begin at Station 7, located at 1441 Saint Peter St. There, HM (Hazardous Materials Unit) 1 and HM 2 are headquartered along with Rescue 1, Engine 7, a mass-decontamination trailer and other hazmat support equipment. However, Station 7 became one of the casualties of Hurricane Katrina - four feet of water remained inside for 10 days. Currently, Station 7 is uninhabitable due to mold, bacteria and structural damage.

Alongside the Mississippi River, behind the Hilton Hotel on the river side of the flood gates next to the cruise ship Sensation, I found HM 1 parked next to a security fence in front of several bright-yellow tents that turned out to be the headquarters for the hazmat team. HM 1 is a 2000 custom-built American LaFrance apparatus. The team also responds with a Chevrolet Suburban, purchased with federal grant funds, for assessment and control. Both units have satellite communications equipment that was installed just a week before Katrina hit. New Orleans Hazmat normally responds for hazardous materials and weapons of mass destruction (WMD) calls to the parishes of Orleans, St. Bernard, Jefferson and Plaqumines.

Captain Don Birou was the officer in charge when I arrived. We sat down at a table in his tent quarters and I heard amazing stories of victim rescues, firefighter survival and hazmat responses following Hurricane Katrina. Having spent over 26 years in the emergency services, I never dreamed I would hear about fire department or hazmat personnel having to operate under such desperate conditions within the United States. Following the hurricane, they survived, operated and rescued thousands of victims under impossible conditions. This would be a day burned into my mind for as long as I live.

Awaiting the arrival of Katrina, New Orleans hazmat personnel were staged in the city's convention center to ride out the storm. Once the storm subsided, personnel emerged to survey the aftermath of the Category 3 storm. Surprisingly, there wasn't the catastrophic damage many had expected. It looked as though New Orleans had dodged the bullet once again. Power was out, but backup systems designed for 24 to 48 hours of operation in the emergency communications center and other facilities in most cases were in full operation.

Reports began to filter in on Aug. 29 that water was flowing over some levees and that some levees were failing. The city rapidly began to fill up with water in low-lying areas as Lake Pontchartrain, swollen by the storm surge of the hurricane, began to flow into New Orleans. The real disaster was just beginning. Ultimately, almost 80% of the city was under water, including the 911 and communications centers and many of the city's fire and police stations. Nearly 70% of New Orleans fire stations were under water or damaged. Some had been looted.

On Aug. 31, backup batteries and generators for the department's communications network went dead. There was no way to replenish the fuel or batteries needed to keep the communications network on line. Firefighters who were on duty the day the levees broke were stranded in the city and on their own once radio and telephone communications systems went down. They were without food and water and, in many cases, without living quarters.

All cellular and regular phone service was disabled by the hurricane. Firefighters were forced to use written messages delivered by runner to exchange information. Satellite phones were the only means of communications and only two of them were available.

Birou was able to contact his sister at the Phillips/Conoco Emergency Operation Center in Houston. He described the dire communications situation in New Orleans and asked whether help could be provided. She made some contacts and within two days there were 10 handheld satellite phones at FedEx in Baton Rouge. According to Birou, once received, those "10 handheld phones became the most important items on the fire department." After about five days, the direct connection on their Nextel phones began working.

Nine hazmat specialists on duty the day of the hurricane ultimately worked 24/7 until Dec. 18, except for a mandatory rehab Sept. 6-12. Personnel from the New York City Fire Department were assigned to New Orleans Hazmat during the rehab period. As New Orleans slipped into anarchy and police protection was limited or non-existent, the superintendent of the fire department told firefighters who had personal weapons to carry them and they became their own police force, protecting themselves and other personnel.

Each new day began with hazmat team members foraging for boats, fuel, flashlights, tire-repair kits, food and water to accomplish the rescue mission before them and for survival themselves. The first 2-weeks their time was spent on rescue operations. One operation at the Louisiana State University School of Dentistry turned out to be the rescue of 100-plus firefighters, police officers and New Orleans Health Department paramedics who were using the structure as a safe haven from the hurricane. Flood waters from the broken levees surrounded the dental school, trapping the personnel for four days.

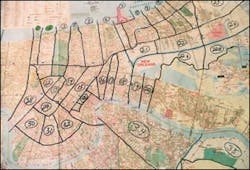

When not conducting rescue operations, the hazmat team members evaluated a list of 93 Tier II Facilities with Extremely Hazardous Substances (EHS). They also searched through 430 facilities without EHS substances, looking for railcars and other hazmat containers with leaks or damage. In addition, they searched for "orphaned" containers carried away from facilities by the flood waters. A grid system was drawn on a map to identify areas of the city that needed to be searched. As of Dec. 7, over 10,800 containers of hazardous materials had been located and evaluated. Examples of containers are listed below:

- Glass bottles - Lab chemicals, solvents, corrosives, oxidizers, flammable liquids, dangerous-when-wet phosphoric materials, toxic, radioactive and unknowns.

- 30- to 70-pound cylinders - LPG and propane.

- 150-pound cylinders - Oxygen, acetylene, helium, argon and nitrogen.

- Drums and pails - Hydrocarbon fuels, oils, solvents, corrosives, oxidizers, flammable liquids, dangerous when wet phosphoric materials, toxic, radioactive and unknowns.

All containers found were checked and marked. Five major Level A entries were conducted for atmospheric testing, evaluation and discovery of hazards in the New Orleans Medical Center of Louisiana (Charity Hospital), University Hospital, Louisiana State University School of Dentistry, Dennis Sheen Transfer Company (following fire and explosions) and 2321 Timoleon St. (unknown release at debris-removal site).

The Louisiana National Guard 62nd Civil Support Team, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on-scene coordinator and START (Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment) teams eventually reached the city as waters started to recede and were an excellent resource during hazmat operations. They provided personnel and hazmat equipment and helped the firefighters survive the first couple of weeks. Civil Support Teams and a small EPA group were assigned under the command of New Orleans Hazmat for operations within the city. Hazmat personnel from Illinois fire departments in Carpentersville, Chicago, Chicago Heights and Decatur assisted New Orleans Hazmat in addition to Gonzales, LA. Approximately 2,000 firefighters from around the country supplemented the entire New Orleans Fire Department in the weeks following Katrina.

There were more than 3,000 railcars in Orleans Parish during Hurricane Katrina. Of those, 640 contained hazardous materials and 105 of those were derailed by the flood waters. Two releases occurred from railcars, one at the CSX rail yard releasing ethylene oxide and another at Air Products Company, releasing hydrogen chloride.

The CG Railway Company is a Mexican operation in which railcars are shipped from Mexico by specially designed barges to off-load in New Orleans. Four of the tracks in the CG rail yard were under water with five derailed cars. Documentation provided by CG Railway showed 14 railcars containing hazardous materials at their New Orleans facility. Materials in the railcars included methylamine, anhydrous ammonia, potassium hydroxide solution and chlorine.

Strong winds and storm surge also caused several cars to derail in the CSX rail yard. One of the derailed cars contained fuming sulfuric acid. Other nearby cars contained methyl acrylate monomer, heptanes and combustible liquids. Several barges were also washed over the levees by the storm surge. One such barge was about two-thirds full of benzene. The barge traveled approximately 100 feet from the levee across an industrial yard, a four-lane highway, and through power poles and a swamp. No damage occurred to the barge and there were no leaks. At the time of my visit, the barge was still resting where it landed, awaiting removal of the benzene by the owners.

Hazmat team members responded to one explosion with fire at 3200 Chartres St. with phosphorus, arsenic, calcium and tin metal involved. They also responded to the Mandeville Street Wharf fire that destroyed a large portion of the massive warehouse. It is estimated that over 1,000 natural gas leaks occurred, a total that was likely much higher. Other missions included hazmat response for Presidential visits on Oct. 10 and 11. Ammonia leaks occurred at New Orleans Cold Storage and Browns Velvet Dairy.

As time went on, rescues were concluded and the flood waters receded, hazmat team members focused on identifying hazardous materials in buildings and homes. As more people returned to the city, call volume increased for hazardous materials discovered in debris piles. Refrigerators and other appliances with freon had to be identified so that contractors could remove the freon before disposal. Fumigation contractor procedures were assessed by hazmat personnel and permits issued for fumigation operations to ensure they were conducted safely.

EMS personnel from the New Orleans Department of Health, about 60% of fire personnel including the hazmat team and other City Hall employees were living on the Sensation, including the superintendent and assistant superintendent of the fire department. Most hazmat team members spent Christmas 2005 away from their families. Life aboard the cruise ships includes room, meals and a nightly movie, but there are no phones or TV. No timetable has been determined for the renovation or rebuilding of damaged fire stations, including Hazmat Station 7. Personnel are taking matters one day at a time and hoping that it won't be too long before life begins to return to normal in New Orleans.

Robert Burke, a Firehouse contributing editor, is the fire marshal for the University of Maryland. He is a Certified Fire Protection Specialist (CFSP), Fire Inspector II, Fire Inspector III, Fire Investigator and Hazardous Materials Specialist, and has served on state and county hazardous materials response teams. Burke is an adjunct instructor at the National Fire Academy and the Community College of Baltimore, Catonsville Campus, and the author of the textbooks Hazardous Materials Chemistry for Emergency Responders and Counter-Terrorism for Emergency Responders. He can be at [email protected].