Hazmat Studies: Oklahoma City, Before & After the Bombing

On April 19, 1995, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols carried out a domestic terrorist bombing on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 and injuring more than 600 people. At the time, the loss of life was the largest in an act of terrorism in the United States. The motive was anti-government sentiment, specifically, retaliation for the sieges that occurred at Ruby Ridge, ID, and in Waco, TX.

A little over 23 years later, we look back on the incident, reviewing the response efforts as well as some lessons learned from such a complex call. But first, we will review Oklahoma City itself, its fire department and hazardous materials team.

City details

Oklahoma City (OKC), the capitol of Oklahoma, is located in central Oklahoma. At 621 square miles, it is one of the largest geographical cities in the United States, with a population of approximately 580,000. The Oklahoma City metropolitan population is approximately 1.41 million.

OKC Fire Department history

The Oklahoma City Fire Department (OKCFD) organized in 1889 as a small volunteer fire company, led by Chief Andy Binns. It operated one horse-drawn wagon housed in a small frame building to protect 10,000 residents. In 1894, the first paid firefighters were given 50 cents per hour for fighting fires. The first motorized apparatus was purchased in 1910.

OKCFD today

Today’s OKCFD, under the leadership of Chief Richard Kelley, has approximately 1,000 personnel operating from 36 stations strategically located throughout the city.Annual alarms totaled more than 70,000 for 2017:

- EMS: 51,283

- Structure fires: 958

- Wildland: 814

- Hazmat: 773

- Vehicle fires: 395

- Other alarms: 19,540

Apparatus includes 36 engines, 13 rescue ladders, two heavy rescue vehicles, one hazardous materials unit, one CBRNE unit, decontamination trailers, and one mobile air unit.

Special teams include hazardous materials, urban search and rescue (USAR), and dive and swiftwater rescue.

OKCFD responds to medical and rescue calls, but it does not transport patients. Transportation is provided by a private ambulance service that is subsidized by the city.

Hazardous Materials Team

The Hazardous Materials Team was started by Deputy Chief Jim Henning in 1984. Johnny Davis, David Bowman and Gary Marrs were selected as the station officers, and they were allowed to hand-select their crews. All the crews then went to the National Fire Academy in Emmitsburg, MD, to receive their initial training.

Station 4 became the Hazardous Materials station. It was located downtown at SW 4th and Broadway. There was an engine and the hazmat rig assigned to the station. Four people were assigned to the station on all three shifts.

The team was not initially staffed full time. When a call came in, it would take the engine and the “HM,” which was an old rescue squad that was refurbished by the Station 4 crews, which were allowed to design and build the inside of the rig. They had an MSA combustible gas indicator, CD V-777 radiation monitors and dosimeters, pH paper, some Level A suits, and some flash suits.

They responded on all hazmat calls across the city.

Hazmat Station 5

Station 5 is the current Hazardous Materials Team station, located at NW 22nd and Broadway. The team has an engine (five/minimum four), a hazmat unit (five/minimum four) and an Oklahoma Homeland Security Regional Response Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear and Explosives (CBRNE) unit (not staffed full time).

Approximately 50 hazmat technicians are on duty at other stations, with a minimum of seven hazmat techs on duty at Station 5 each shift. If needed, off-duty personnel can be called in. Hazmat team members receive technician-level training and hazmat chemistry. All other firefighters are trained to the operations level.

Mutual aid is available from the 63rd Civil Support Team located in Oklahoma City, and a foam tanker from Tinker Air Force Base.

OKCFD hazmat units carry typical hazardous materials equipment and supplies. Scott air packs with 1-hour bottles are used for most respiratory protection. Air-purifying respirators are also available if needed. Chemical suits are Kappler Zytron 300 for Level A and Tyvek for Level B. In-suit communications use throat mikes and hand signals.

Tow trucks in the city carry absorbent materials for spills up to 10 gallons of liquids and 5 pounds of solids. For spills of greater quantity, the hazmat team responds. A typical hazmat call includes the companies originally called, Hazmat 5 and Engine 5. If a decontamination trailer is required, Rescue 8 responds to provide personnel for the trailer.

Hazmat exposures

Transportation hazmat exposures include Interstates 35, 40, 44 and 235, and state routes 3, 14, and 66. Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Union Pacific railroads cross through the city as well. Pipelines carrying crude oil and jet fuel are located within the city limits. Fixed-facility exposures include Oil Well leaks, Research Park Medical Research, the State Department of Agriculture, the State Health Department, tank farms citywide, water treatment facilities, 3M company, U.S. Foods, Cold Storage OK, an ethanol blending facility, Cotton Mill COOP, Miniky and Xerox.

Murrah Building bombing

The Oklahoma City Fire Department has responded to numerous hazmat incidents, the largest being the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building. The blast from a 4,800-pound mixture of ammonium nitrate, nitro methane and fuel oil destroyed one-third of the nine-story building. The blast was heard 16 miles away andResponse efforts

While I was teaching a one-week Hazmat Incident Command Course for the National Fire Academy for the 63rd Civil Support Team, there was an officer from the OKCFD in the class. He was one of the first chief officers on the scene of the bombing. He was kind enough to offer a walking tour of the bombing site that had been turned into the National Memorial. He provided an overview of his actions and those of OKCFD during the response. That personal touch made my tour of the site much more meaningful and informational.

One of the things I learned was that the Federal Building was not the intended target of McVeigh. When McVeigh and Nichols scouted the site, they chose the Federal Courthouse across from the Federal Building. However, when they arrived to place the truck bomb, street work was being conducted in front of the courthouse so the truck could not park there. The Federal Building then became a target.

Immediately following the bombing, more than 1,800 calls began pouring into the 9-1-1 center. Within 23 minutes, the State Emergency Operations Center had been activated. Within the first hour, 50 people had been rescued from the rubble and sent to hospitals throughout the area.

During the response phase, there was so much help coming from citizens and emergency personnel that no security zone could be created. A local TV station broadcast, without being told to do so, that all available doctors and nurses should respond to the scene. This created problems with accountability. Everyone was focused on saving lives, but because of the circumstances, managing the scene became difficult at best. One nurse who responded to the call for help was searching for victims when she was hit on the head by falling debris and killed.

During the search, someone thought they found another bomb and the site was evacuated along with a four-block area around the building. This gave incident commanders a chance to gain control and secure the site, and identification tags were issued to those who had a legal responsibility to be operating at the site.

Communications was an issue during the incident. Groups of responders were not able to talk to other groups. As a result, many did not know what others were doing. People evacuating the scene clogged roads and delayed emergency vehicle response to the scene. At the time of the bombing, Incident Command was new to the fire department, and it was in a learning process. Incident Command involved a culture change, and not all officers were using it. Fire Chief Gary Marrs got on the radio during the bombing response and told the officers to set up command and start using the Incident Command System. After that incident, ICS was used by the department all the time.

Hazmat and SAR

Station 5 was located about 18 blocks from the Murrah Building. The crew had just finished morning duties, cleaning the station and mowing the yard, when there was a very loud boom and the building shook. Everyone went outside to see what had happened. There was a large plume of smoke coming from downtown.

Station 5 (Engine 5, Truck 5 and HM 5) self-dispatched and were the first OKCFD rigs on the east side of the incident. Chris Fields was the officer on the HM. Part of E-5 and HM-5's crew set up a triage area, and the others went to the building to perform rescues. Truck 5 laddered the building on the east side and rescued people from the upper floors.

After the secondary bomb scare was cleared, HM was assigned to the second and third floors, and spent the rest of the day searching through the rubble for victims and removing them.

In the following weeks, the HM returned almost daily to help clear debris and to remove victims. The HM also set up a weather-monitoring station and some decontamination stations.

Eleven FEMA USAR teams were dispatched to the site. OKCFD did not have a USAR team at the time of the bombing. In the years following, several members received USAR training. FEMA was adding a team, and Oklahoma City hoped it would be the one. However, Missouri was selected. Eventually, the Oklahoma Department of Homeland Security funded a state USAR team. The current team is composed of an Oklahoma City metro team and a Tulsa metro team. When combined, they are a Type 1 USAR Team. Oklahoma Task Force 1 (OK-TF1) also has a K-9 team with eight dogs in Oklahoma City and 10 in Tulsa. Firefighter Jeff Hanlon trains USAR search dogs, and a dog named Willy is currently in training. Both teams have a swiftwater rescue component and a helicopter search-and-rescue Team. Oklahoma Air National Guard flies the helicopters and OK-TF1 rides the hoist.

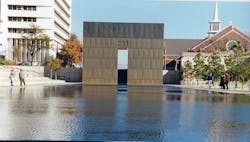

Oklahoma City Bombing National Memorial

On May 23, 1995, what remained of the Murrah Federal Building was demolished. Planning for a fitting memorial erected in its place carried on for two years. Today the site includes a memorial and museum.According to Kari Watkins, the executive director of the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum, “The memorial was built to remember those who were killed and those who survived and those who were changed forever.”

One of the most outstanding features of the memorial are the two “Gates of Time,” each at the end of the reflecting pond. The concrete gates are covered with a Naval and yellow bronze. On one of the gates is the time 9:01, representing the last moment of peace. On the other gate is the time 9:03 representing the first moments of recovery.

For me, the most moving part of the memorial was the 168 bronze chairs, each engraved with the name of one of the victims. Large chairs represented the adults and small chairs the children. Also on the memorial site is a 70-year-old American elm, “The Survivor Tree,” tilted by the force of the explosion, but still standing. I have been to the memorial twice. On my second visit, I brought my 5-year-old granddaughter Abby. My wife and I explained the memorial to her. Following our explanation of the chairs, Abby immediately ran to a chair and hugged it. I believe she understood the purpose of the memorial.

Investigation and trial

Just 90 minutes after the explosion, McVeigh was captured about 62 miles North of the city. McVeigh’s car was missing the rear license plate and was stopped by Oklahoma Highway Patrol Officer Charlie Hanger, who arrested McVeigh for carrying a concealed weapon. Officer Hanger had no idea that McVeigh was the bomber. McVeigh was taken to the Noble County Jail, and his clothing was collected and put in paper bags.

As the FBI began its investigation, evidence quickly lead to McVeigh. Evidence collected at the bombing scene lead to a vehicle identification of a truck rented in Kansas. On April 20, the FBI released a sketch of McVeigh obtained from the truck dealer’s description. A motel owner in Junction City, KS, recognized the person in the sketch as a guest who had registered at the motel as Timothy McVeigh. The FBI ran an arrest records check on McVeigh and found he was in custody at the Noble County Jail in Perry, OK. Additional investigations led to McVeigh’s Army buddy Terry Nichols and he was arrested as well. FBI Agent Barry Black said of the investigation, “It went as it was supposed to.”

Nichols was tried, convicted and sentenced to life in prison. McVeigh was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was executed on June 11, 2001.

More information

For additional information, contact Captain D.J. Harris at (405) 557-6980 or [email protected] or Major Shawn Benn at [email protected].

About the Author

Robert Burke

Robert Burke, who is a hazardous materials and fire protection consultant and who served as a Firehouse contributing editor, is a Certified Fire Protection Specialist (CFSP), Fire Inspector II, Fire Inspector III, Fire Investigator and Hazardous Materials Specialist. He has served on state and county hazmat teams. Burke is the author of the textbooks "Hazardous Materials Chemistry for Emergency Responders," "Counter-Terrorism for Emergency Responders," "Fire Protection: Systems and Response," "Hazmat Teams Across America" and "Hazmatology: The Science of Hazardous Materials."