Prehospital Patient Care & CPAP for Children

Key Takeaways

- Any child who shows increased work of breathing who EMS providers encounter should be considered for CPAP as an alternative to intubation to stabilize the child’s breathing.

- The greatest barriers to pediatric CPAP are logistical and cultural: mask fit, training, arbitrary age cutoffs and equipment.

- Outfitting a medic unit with pediatric CPAP capability usually costs less than $300.

When the call comes in for a child in respiratory distress, every paramedic feels the weight of the moment. For Kyle Goodknight, that moment didn’t come while he worked in his medic unit; it came in his home when his six-year-old daughter, Camdyn, suddenly slipped into severe respiratory distress.

Just days earlier, Camdyn’s brother had shaken off a bout of croup. However, Camdyn’s symptoms escalated quickly. Her oxygen saturation at home read 87 percent, and her pale, exhausted look told Goodknight that she was eperiencing something more than a mild episode. He rushed Camdyn to urgent care. From there, she was transferred straight to Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH.

In the ED, things went from bad to worse. Camdyn’s blood pressure plummeted to 40/0. The team prepared to intubate, which is a moment that no parent ever wants to witness. However, as both a respiratory therapist and a paramedic, Goodknight had one thought: Intubation wasn’t the only option. He spoke up.

“Do you have BiPAP?” he asked. “Can we try BiPAP on her? We’ll know in three or four minutes if it’s going to help.”

The physician agreed, and within minutes after starting BiPAP, Camdyn’s breathing stabilized.

Ultimately, Camdyn spent about 16 hours on BiPAP in the ICU with blood pressure support and avoided the risks and complications of intubation.

That day in the ICU, Goodknight’s colleague and friend, Firefighter/Paramedic Rob Glaze, stood at Camdyn’s bedside and watched her improve. Glaze asked a question that changed everything: “Kyle, why aren’t we doing this in EMS?”

A pediatric care movement

At the time, EMS protocols typically limited CPAP to children at least 12 years old. However, here was a six-year-old child proving that pediatric CPAP could be effective and lifesaving.

Glaze’s question launched a mission, one that would bring pediatric CPAP into EMS protocols across Ohio and beyond.

Glaze, his medical director and physicians at Nationwide Children’s partnered with equipment manufacturers and EMS leadership to solve the barriers: protocol revisions, pediatric full-face masks and, most importantly, provider training. What began as a terrifying night for Goodknight’s family grew into a movement that continues to reshape pediatric prehospital care.

CPAP for children: When?

Respiratory complaints account for nearly one-third of pediatric ED visits and remain a leading cause of hospitalization and death. Unlike adults, children who go into cardiac arrest almost always do so because of respiratory failure, not cardiac causes.

The Pediatric Assessment Triangle is a quick way to identify children who are in distress (i.e., work of breathing, circulation and appearance). Early recognition allows EMS providers to intervene before hypoxia leads to cardiac arrest: If prehospital care can stabilize a child’s breathing, the cascade of deterioration can be prevented.

Any child who shows increased work of breathing should be considered for CPAP. Common features include:

- Retractions (intercostal, suprasternal, subcostal).

- Grunting: the child’s attempt to generate positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP.

- Nasal flaring.

- Belly breathing or abdominal muscle use.

- Somnolence or lethargy following prolonged distress.

In adults, pursed lip breathing is considered a sign of severe respiratory distress. In children, grunting is the same thing: They are generating intrathoracic pressure to keep the airways open.

CPAP is a well-established modality for children in the hospital setting. Studies show CPAP reduces intubation and decreases hospital length of stay. Additionally, the National Association of EMS Physicians recommends the use of CPAP in the prehospital setting for children as a safe alternative to intubation. It’s time that EMS adopts this recommendation across the nation and gives children the same treatment that adult patients are afforded.

Indications for CPAP in children are broad and mirror the hospital setting. In central Ohio, CPAP succeeded in the following:

- Asthma: Helps overcome bronchospasm, works synergistically with albuterol.

- Bronchiolitis: Most common in children who are younger than two years old, it’s defined by inflammation and collapse of medium-size airways.

- Croup: As in Camdyn’s case, CPAP stents open the upper airways and can prevent intubation.

- Pneumonia: Supports oxygenation and work of breathing in severe cases.

- Submersion injuries/drownings: Children often arrive hypoxic but not in arrest; CPAP can stabilize them until recovery.

- Consistent outcomes: Improved oxygenation, decreased work of breathing, calmer patients and less frantic families.

What’s noted above saved children from intubation because EMS had the right tools and training.

Equipment and training

The greatest barriers to pediatric CPAP have been logistical and cultural.

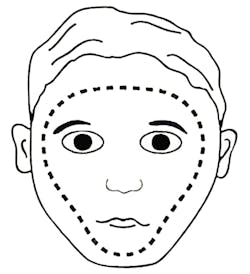

Mask fit is everything. A poorly fitted mask can leak and frustrate both the child and the provider. The key to successful CPAP in the field is implementing the full-face mask, which goes below the lower lip and above the eyebrows. This type of mask addresses many of the issues that often affect the adult population with mask fitting. With the right size, many children tolerate CPAP surprisingly well. Some even relax or fall asleep once their breathing eases.

Training builds confidence. It isn’t enough to hand out a new protocol. Crews need hands-on practice with pediatric manikins, fittings and real-world scenarios. In our training sessions, we emphasize recognition of respiratory distress and skills training, including proper mask sizing and placement, utilization of existing CPAP generators on apparatus and the proper connections of all necessary equipment.

Age no longer is a barrier. If the mask fits, the child is a candidate. Local protocols have removed arbitrary age cutoffs, which allows providers to act on clinical presentation instead of paperwork restrictions. CPAP is safe and effective at all ages.

Equipment investment is minimal. The typical setup includes two infant-size full-face masks, one small adult full-face mask (for older children), proper fittings for the chosen CPAP generator and tubing connectors. Outfitting a medic unit with pediatric CPAP capability usually costs less than $300, including masks and adapters.

Changing the culture in EMS

When CPAP for adults was introduced, many resisted, viewing it as too aggressive.

Now, it’s standard care. Pediatric CPAP is following the same path. To make it standard practice, agencies must:

- Shift mindset: CPAP isn’t aggressive; it’s noninvasive support that can

prevent a child’s decline. - Invest in the right equipment: Pediatric masks that fit well are essential.

- Train frequently: Recognition and comfort only come through repeated practice.

- Celebrate progress: Recognize instances when CPAP was used for children and share it’s success with your department.

It isn’t about making pediatric care complicated; it’s about giving providers a simple, safe tool that changes outcomes.

CPAP saves children

Camdyn’s story is more than one family’s crisis; it’s the reason that our local EMS agencies now carry pediatric CPAP and the reason that children across central Ohio are avoiding intubation in the back of a medic unit.

The clinical evidence and frontline experience point to the same conclusion: CPAP saves lives, prevents intubations and improves outcomes. It’s safe, well-tolerated

and effective even in the youngest patients. Every child in respiratory distress deserves CPAP as an option.

Today, Camdyn is a healthy, 20-year-old woman who’s in nursing school. Her story lives on in every medic who now has the option to reach for CPAP when a child can’t breathe.

This article was created with the assistance of generative AI tools and was edited by the authors and Firehouse’s content team for clarity and accuracy.

About the Author

Chelsea Kadish

Dr. Chelsea Kadish is director of EMS for the Division of Emergency Medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of pediatrics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. She also serves as assistant medical director for Columbus Department of Fire, MedFlight of Ohio and Metropolitan Emergency Consortium. Kadish received her medical degree from Tulane University School of Medicine. She completed her pediatrics residency at New York University and her pediatric emergency medicine fellowship at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Kadish also completed a fellowship in EMS at The Ohio State University. Her clinical and research interests include pediatric prehospital care, with a current focus on prehospital resuscitation.

Kyle Goodknight

Kyle Goodknight is a paramedic and respiratory therapist who has nearly 30 years of experience in hospital-based patient care and EMS. He serves with Delaware County EMS as a front-line paramedic and shift clinical educator, where he combines hands-on response with training responsibilities to ensure high clinical standards across the department. Goodknight’s career has centered on airway management, innovative procedures and clinical education. As an educator and public speaker, he has trained hospital staff and EMS providers across the state of Ohio, shaping the next generation of emergency medical professionals through mentorship, scenario-based instruction and continuing education initiatives.