Challenges Overcome, Objectives Met As Florida Task Force 1 Responds to New Orleans

Hurricane Katrina will go on record as the costliest natural disaster to strike the U.S. and one that resulted in the largest mobilization of National Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) assets in the history of the National USAR Program. Florida Task Force 1 (FL-TF1), comprised primarily of members of Miami-Dade Fire Rescue (MDFR), and no strangers to the damaging effects of hurricanes, played an integral role in the local and national response in the aftermath of Katrina.

Days before Katrina wreaked havoc on the Gulf Coast, the hurricane made landfall in South Florida on the evening of Aug. 25. The strong winds and rain cut a swath through South Florida, directly impacting Miami-Dade County. Immediately after the winds subsided, MDFR and elements of FL-TF1 were mobilized to assist with the rescue efforts, from conducting canine searches of devastated mobile home parks to searching the rubble of a collapsed concrete overpass. In the days to follow, FL-TF1 personnel coordinated the local humanitarian relief efforts by establishing ice and water distribution stations throughout Miami-Dade County. All of this took place while the homes of many of the members were in need of attention as well.

Days after the storm had made landfall in South Florida, it was evident that the Gulf Coast was next. On the morning of Aug. 29, FL-TF1 received Federal Activation Orders to deploy immediately as a Type III, 34-person "Light Task Force" to Baton Rouge, LA. The Light Task Force concept (28 people with six support specialists) is a departure from the traditional 70-person Type I Task Force and was a few years ago to deploy to events such as this. A Type III team focuses on hurricanes where search and rescue of the entrapments are a result of lightweight construction collapses. The national hurricane deployment model developed after the 2004 hurricane season paired two Light Task Forces with a Full Task Force. FL-TF1 personnel were assembled, the equipment cache secured and the task force was enroute for what was expected to be an 18-20 hour trip.

Because of the emergent nature of the mission, the task force leader, in consultation with the team medical and safety officers, decided to drive straight through, stopping every 300 miles for fuel, personnel relief and to switch drivers.

While enroute, the task force leader maintained frequent communications with the national USAR command center as well as the FEMA/USAR Incident Support Team (IST) assigned to the region. Prior to leaving Florida, the task force was re-directed to New Orleans by the IST. Because of the devastation in Alabama and Mississippi, the most direct route to New Orleans was nearly impossible to traverse.

The task force planning team manager and technical information specialist were assigned the responsibility of charting a route into New Orleans. Communications with IST personnel now in all of the affected states provided real-time information that assisted in planning the most direct route, through Alabama into the middle of Mississippi and then south into Louisiana. The trip took approximately 25 hours. Once FL-TF1 entered Mississippi, vehicles maintained fuel levels at three quarters because of anticipated fuel shortages in the area.

The point of assembly for federal USAR assets was Metairie, LA, just outside New Orleans. After FL-TF1 arrived on the evening of Aug. 30, personnel were tasked with establishing their base of operations (BoO) and were required to attend the night's planning meeting. At first light on Aug. 31, FL-TF1 was assigned with other federal USAR task forces to perform rescue, hasty searches, primary searches and victim triage in the flooded areas northwest of downtown. This mission required the use of watercraft provided by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) contractors. Based on information provided by other task forces from Texas and Missouri, which had operated on the previous day, FL-TF1 decided to use as many personnel as possible to provide for an effective search-and-rescue operation. The 34-member multi-disciplined team was split into two-person search groups. Hand tools were carried on each boat to facilitate forcible entry and light extrication. In addition, chainsaws were available to ease roof opening. On this first day the use of airboats proved beneficial as they were able to traverse the flood areas as well as the dry ground around the levees. In our initial search area, two levees divided the grid and impeded the movement of victims to safe refuge. Utilizing traditional boats necessitated multiple entrances and exits of victims as well as the need to carry the boats over dry ground.

On the first day, FL-TF1 personnel recorded almost 400 rescues. Task force medical personnel and a representative of the U.S. Coast Guard, established a victim triage/receiving area on Interstate 10. From this location, the team physician and two medical specialists triaged over 1,700 victims in an eight-hour period. In the days to follow, hundreds more would be rescued, and those wishing to stay were charted with GPS and given water and "meals ready to eat" (MREs). The locations of deceased persons were also plotted with GPS coordinates for later recovery.

The goal early on was threefold. First, locate and remove those in obvious distress. Second, conduct hasty searches in the inundated areas to locate and then remove or assist those trapped and not readily visible. Finally, task forces conducted more systematic primary searches where they went from structure to structure searching and marking each building. This became a monumental task and one that required the assistance of many more personnel. Search areas were assigned to each task force and, with the assistance of federal partners from the EPA as well as local and state law enforcement agencies, the search areas were effectively covered. In addition to the victim assistance, FL-TF1 personnel and other task force personnel coordinated the evacuation of 57 elderly people from a nursing home that had been flooded days earlier.

Contrary to many early media reports, a coordinated search-and-rescue effort was mounted right after the storm and continued for many days to weeks and involved personnel from the national USAR system. While the scale of the disaster was immense, personnel worked diligently to get the job done.

Each USAR mission is different. While the need is always the same - to locate and remove trapped victims - many times those victims are already deceased. Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of this deployment was the fact that hundreds of people were saved by the USAR task forces that operated in the New Orleans area.

After nine days and almost 1,000 rescues, FL-TF1 was demobilized and directed to return home. While there was still a lot of work to be done, the national USAR system had the depth of resources to rotate new teams in and provide the initial teams with much-needed relief. Furthermore, for FL-TF1 there was again a sense of urgency, since Florida was still in the middle of what had already proven to be a very active hurricane season and a new storm called Ophelia was looming in the Atlantic. FL-TF1 departed Louisiana and reached home on Sept. 8.

Six days later, FL-TF1 again received activation orders to deploy an 80-person Type I Task Force to New Orleans. A new team was assembled and the equipment cache secured for the over-the-road trip.

The second deployment had a new mission objective. Task force personnel were charged with performing a labor-intensive house-to-house secondary search. FL-TF1 was assigned the area known as the "Ninth Ward," one of the hardest-hit areas. Because of the time that had elapsed since the storm, it was clear this time the team would be operating in more of a recovery mode as opposed to the previous rescue mode. This would be a slower, more methodical mission that didn't come with the satisfaction of multiple live rescues. The morning briefings consisted of reviewing the rules of engagement on how to conduct the secondary searches and what to do when encountering human remains.

On the first operational day, FL-TF1 rescued a man and his dog that were unable to get out of a house for 19 days. The man was the only live victim to be rescued during FL-TF1's second mission. The initial excitement of a live rescue was short-lived as no other live victims were discovered. In 12 days, FL-TF1 performed over 5,000 secondary searches and recovered nearly 30 bodies.

The first mission to New Orleans concentrated on search and rescue in a floodwater environment. The second mission was more of a forcible entry, search and hazardous materials-like decontamination event. The structures that needed to be searched had been initially searched in a hasty manner by the first groups who responded to the area. Most of the homes had been under water, and USAR members initially searched these structures by boat. Search markings were made high up on the walls and even on rooftops. Task force rescue and search team managers, working with the technical information specialists, made a grid of the area to be searched. GPS units were issued to team members and the searching began.

The post-flood conditions provided for an unusual situation: All of the items in a structure, from beds and tables to appliances, books and shoes, became items floating and moving about as if in a large pot of soup. When the waters receded, all of these items made their way toward the traditional means of egress: windows and doors. Furniture blocked doors and windows. This provided a challenge for task force members attempting to gain entry for search.

FL-TF1 is primarily composed of firefighters from Miami-Dade Fire Rescue. The firefighter skill set was extremely helpful during this mission. Traditional forcible entry skills were particularly beneficial. Task force members were provided a rare opportunity to practice all types of forcible entry techniques hundreds of times. In addition, when the standard methods failed, members improvised. The blocked doors led them to remove upper hinges and push the doors down. Most of the homes they encountered had metal bars on the windows and doors.

Conditions in the houses were beyond belief. Household items were seen hanging from ceilings and attic spaces. Furniture stacked upon furniture in unusual patterns, precariously balancing and stuck together by mud. The water in the homes turned to mud and spent several days percolating in the heat. Mold formed on every surface in the house. Team members wore long-sleeve shirts, gloves and respiratory masks. The conditions were hot, humid and dangerous. When the team encountered human remains, the IST was contacted and members of the task force stood by respectfully until the body recovery team arrived.

At the end of each day's operation, every member had to go through gross and technical decontamination because of the previous flooding sewers spewed human waste. Decomposing human and animal bodies, chemicals, fuels, mud and other contaminants made their way onto anyone working in the area.

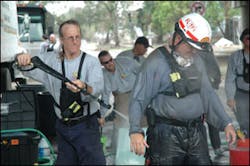

Task force hazardous materials specialists established the decon areas. Given the viscosity and stickiness of the mud, water-pressure cleaners were used. As the days went on, the efficiency of the decon process improved dramatically. An assembly line approach was used that included rest, rehab and hydration stations. As FL-TF1's hazmat personnel became more efficient, other task forces and various law enforcement agencies came to undergo our technical decon.

Even though FL-TF1 personnel are accustomed to working in high heat and humidity environments, a few members became dehydrated during the first operational period. All members carried water with them to the field; however, given the high temperatures and physically demanding work, team members needed much more fluid than could be carried by individuals. Because of the hydration challenge, task force personnel were assigned to roam the area in a truck, delivering cold water and sports drinks. Rest and hydration breaks were imposed on the search groups throughout the day. As a result of the imposed hydration breaks, there were only a few occurrences of task force personnel requiring treatment for dehydration. FL-TF1 personnel suffered no significant injuries or illnesses during either deployment. This was a direct reflection on the care and preventative measures taken by task force medical personnel.

After 13 days in New Orleans, enduring the high heat and humidity as well as the outer bands of Hurricane Rita, FL-TF1 was demobilized and returned home.

Dave Downey is a 23-year veteran of the fire service, currently the chief of the Training and Safety Division with Miami-Dade Fire Rescue. In addition, he is a Task Force Leader for Florida Task Force 1 (FL-TF1) and led the Type III Task Force on the first response to New Orleans. Eric Baum is a lieutenant with Miami-Dade Fire Rescue, assigned to the Fire Investigation Bureau. He is a technical information specialist with FL-TF1 and responded with FL-TF1's Type I Task Force to New Orleans.