High Risk/High Reward - Searching for Life on the Fireground - Part 2

This article is part of a series of articles focused on considerations for primary search.

We continue to lose approximately 100 firefighters in the line of duty each year. Running out of air, after becoming lost and disoriented while performing a search, is the second leading cause of firefighter deaths and injuries while operating on the fireground. The searching of a burning structure is a firefighting basic and falls into the category of subject areas that firefighters should spend a majority of their training time. As the job of firefighting changes, performing aggressive searches for trapped occupants is becoming more of a low frequency event with high risk potential.

Speed during search operations is crucial. Even though fire doubles in size each minute, its intensity increases 18-fold in that same time period. The clock is running - people are in trouble within a hostile environment and need our help. The hostile environment faced by firefighters and victims today presents toxins in very high concentrations as well as possibilities of rapid fire spread and structural failure due to building construction features. Because of the chemical make up of items used in our lives, these toxins are being released readily upon ignition and temperatures are rising to flashover thresholds very quickly.

A primary search is to be a quick sweep of the areas that we suspect victims to be located. A standard size bedroom should realistically take no more than 30 seconds to effectively search in a primary mode. Although speed is important, it must not be forgotten that keeping oriented must never be sacrificed. Secondary searches, most often performed when fire conditions are somewhat controlled, should be more deliberate and thorough.

Searching firefighters should remain low while performing search operations to afford them the most visibility as well as to allow them to operate in cooler temperatures. Too often firefighters are being trained to perform search operations crawling on their hands and knees holding onto and following each other in a line while maintaining a wall much like a mother duck with her ducklings close behind. This does not constitute an effective search pattern or lend itself to speed of operations.

Firefighters searching in this manner are forced to look down at the floor feeling the way in front of them as they approach. Conditions above and out in front of the team are often not able to be monitored. In this position, a firefighter may also be suspect to falling down a staircase or through a weakened floor and not be able to stop themselves since the weight of their SCBA and helmet is pushing them forward. Assuming a position on their haunches with their head upright and a leading leg extended assists the firefighter in monitoring changing fire conditions as well as keeping their weight back if they encounter an opening or weakness in the floor in front of them. This position also allows a firefighter to move quickly through the area that they must search.

Consideration should also be given to the number of firefighters committed to search a particular area. More is not necessarily better in this regard. An example to this point would be the instance of searching bedrooms in a residence; having more than one firefighter searching a 10-by-10 room would lead to them crawling over each other, slowing down the search and possibly even missing the victim that they are searching for.

A recommended practice in this case is for one firefighter to search the room and have the other maintain the doorway or point of orientation while monitoring fire conditions. When the search team gets to the next room, the firefighters can switch roles allowing the firefighter that has already worked a chance to rest. This will permit the search team to use their air supply in the most efficient manner. Remember, the search team is only as strong as it's weakest link - the lowest air cylinder pressure. Maintaining air supply awareness can not be forgotten.

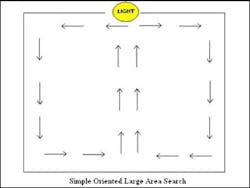

If two firefighters are going to search a room, an effective search method is to leave a light at the entry point (a good reason to carry two flashlights) and have one firefighter search right upon entry into a room and the other to search left. This is sometimes referred to as an oriented search method. Both firefighters should cross at a midway point in the room and meet back at the entry point. Advantages of this type of search is that it is quick and it provides for areas in that room to be searched twice by different firefighters.

As a general rule, search efforts should start closest to the fire working back towards the point of entry but the conditions or situation may dictate otherwise. Victims located nearest the fire are in the most danger and must be removed quickly to have the best chances of survival. When conducting a search of the fire floor, firefighters should go to the fire area and search back towards their entry point. If possible, the firefighter on the nozzle of the hoseline should perform a quick visual search of the fire area prior to opening up on the fire. Once the thermal balance of the area is disturbed, visibility will be decreased significantly.

Searching Above the Fire

Following in order, victims trapped above the area of fire are in the next greatest degree of danger. This is the most dangerous location on the fireground for search efforts. If it is necessary to search above the fire, make certain that the incident commander (IC) and interior crews know you are going above the fire. The stairwell that a search team ascends should be protected by a hoseline until they are back down. Even prior to ascending to the floor above the fire, crews should try to get an idea on the location of the fire and also formulate a plan of escape if they should run into trouble.

As firefighters search above the fire, it is imperative that they be kept informed on fire conditions below them and on the exterior. Extreme caution needs to be exercised when going above the fire in wood-frame or Type V construction as rapid fire spread is very possible.

Firefighters should begin their search immediately upon entering the floor above and work their search towards the fire as conditions can change very rapidly necessitating their egress. Once beginning the search, the location of any victims can be very dependent on the situation presented.

Human Habits can Lead Search Crews to Victims

Obvious clues as to where to search determined from information given to the firefighters can be invaluable. An example of this would be the case of parents telling firefighters that their child is trapped inside their room; asking a question such as how old the child is can help firefighters pinpoint the areas where a search may be successful. In this instance, if the parents reply that the child is an age indicative of an infant or newborn, the firefighters know that the child is going to be located inside the room indicated, more than likely in a crib or playpen since a child of that age is still immobile. On the other hand, if the reply is that the child is a toddler or above, the search becomes more difficult since the child is mobile and may have attempted to escape the area or hide from the fire conditions. A general rule is that children will become scared and will try to hide (examples: in toy boxes, closets, behind furniture, under beds) and adults will try to escape under fire conditions.

Since humans are creatures of habit, most adults will be found in the pathway of exit that they routinely use in their residence, sometimes ignoring and passing exits that are readily available for escape. Areas behind doorways and below windows are other areas where adult victims are often found. No area can be discounted however as adults victims have also been found in closets under clothes and in bathtubs or showers with the presumption that water would protect them from the fire.

If a victim is found, search the immediate area for other victims as it is very common to find family members in groups if trapped. Calling out routinely ("Fire Department! Anyone in here?") during a search may help locate victims if they are conscious and able to here you. After calling out, it is recommended that searching firefighters pause momentarily, stopping their breathing from their SCBA and listening for any weak moans or calls for help. Stopping to listen regularly during the search can also clue the team in on fire advancement and also progress by other fire companies (water hitting the fire, saws running or ceilings being pushed down by roof teams, glass being broken etc.). Some of the routine radio traffic or fireground sounds can also be invaluable later on if it becomes necessary for the team to abort the search and evacuate immediately through an alternate exit than originally planned.

Communication is Vital During Search Process

Search activities on the fireground need to focus on fire as well as life. It is imperative that search activities be closely coordinated with suppression and ventilation efforts on the fireground to avoid further hostile conditions being forced upon the search team. Search crews should ventilate as they progress, provided that it will not draw fire to their location or cut them off from their egress point. This action, known as venting for life, will allow heat and smoke to lift improving the search conditions as well as the tenability factor for victims. If a window is broken, for ventilation or not, the search team should make it a point to take a "quick look" out the window to orient themselves to their location on the fireground. If fire conditions are encountered, they should be isolated by closing a door or other means if possible.

Whatever actions are taken, it is important that the search crew communicates in an effective manner. This is not saying that they should waste valuable and precious time by stopping to give a "play by play" report but rather a very brief report to keep the IC updated on the conditions that they are experiencing, what actions they may be undertaking and any special needs that they may have (such as ventilation in a specific area, additional line for extension, etc.). This information can directly affect the IC's strategic plan. Letting the IC know your location can also help if the search crew needs help in an emergency regarding the placement of ladders, additional hoselines or RIT deployment.

In turn, the IC must not take it for granted that the interior search crew can see the same conditions that they may be observing on the exterior. Reading the building, assessing rescue profile, evaluating smoke and fire conditions by the IC must be continual since the fireground is dynamic and ever changing as the incident progresses. The IC must let the interior search team know what is happening on the exterior! Overlooking this important aspect of communication has contributed to numerous firefighter line of duty fatalities. Time stamp types of communications can also be very beneficial in the area of air management. Hearing that the crew has been in for a called out length of time can also prompt the officer to perform an air check with his crew. Again, this is not meant to be an ultimate solution as everyone must exhibit responsibility for their own air management while working on the fireground - it's your life, why would you place it 100 percent in someone else's hands to manage your air in a hostile environment?

The search of fire buildings can be one of the most rewarding actions taken on the fireground but can also be the most hazardous duty performed. Searches for the rescue of trapped occupants are often performed under the most adverse conditions where a matter of even seconds can mean the difference between success and failure. Continual training in the basic areas of firefighting is a mandatory requirement if success is expected. Is your crew ready to meet this challenge?

JEFFREY PINDELSKI, a Firehouse.com Contributing Editor, is a 18-year veteran of the fire service and currently serves as a battalion chief with the Downers Grove, IL, Fire Department. Jeff is a staff instructor at the College of Du Page and has been involved with the design of several training programs dedicated to firefighter safety and survival. Jeff is the co-author of the text R.I.C.O., Rapid Intervention Company Operations and is a revising author of the 3rd edition of the Firefighter's Handbook. He participated in Training & Tactics Talk on [email protected] To read Jeff's complete biography and view his archived articles, click here. You can reach Jeff by e-mail at [email protected].