Strategy and Tactics for Large Enclosed Structures - Part 3

Of utmost importance to the safety of firefighters concerns the need to understand that with the exception of the officer using a thermal imager (TIC), the remaining crew members may initially or at some point during the incident, be operating in zero visibility conditions for the duration of the enclosed structure incident. Therefore, for safety, firefighters are to use the buddy system and maintain company integrity using physical or verbal means to communicate.

Firefighters must also maintain proximity to or continuous contact with a handline. A handline, which serves as a life line to the exterior, should be used by all firefighters when entering, operating in, or exiting the structure. This safety procedure must be strictly followed and enforced and pertains to all firefighters who enter the structure, including but not limited to, members of engine companies, rapid intervention teams, truck companies, chief officers, sector officers, training officers or safety officers.

It is also important that handlines advanced into the structure remain in place during an evacuation to ensure all firefighters have a means to escape. In addition and for any reason, should a firefighter from a company need to exit the structure, the entire company must exit at the same time and command must be informed. When an entire crew does not exit together, company integrity, which is the firefighter's safety net is lost.

Implementation of Standard Operating Guideline

A large enclosed structure Standard Operating Guideline (SOG) should be implemented when arriving companies encounter the following conditions:

- An enclosed structure measuring 100 feet by x 100 feet or greater in size

- Smoke showing on arrival

- The location of the seat of the fire is unknown

- There is no life hazard present.

For discussion, we'll use the example of light smoke showing on arrival from an enclosed structure measuring 200 feet by 200 feet and 25 feet high. The response will consist of four engines, two trucks, one command officer, one safety officer and one emergency medical unit. The planned response in your department, however, will be tailored to personal preference based on the hazards of construction, hazards of contents, available staffing and equipment and when necessary, should include resources from mutual or automatic aid departments to help achieve the goal of preventing firefighter disorientation, serious injuries and line-of-duty deaths.

When a primary search is not required, the first arriving officer implements the SOG which involves a more cautious approach. A firefighter, with a TIC, then conducts a 360-degree walk around in search of fire, noting the location of pre-existing enclosed windows or doors which may serve as a means of access or evacuation and for the signs of a basement. During this walk around however and typical of fatal enclosed structure incidents, fire indicating the location of the fire will not be visible even with use of a thermal imager.

An attack on a concealed fire may be safely made only when the seat of the fire is located and conditions assessed. In this effort, the officer on the first arriving engine company will lead the crew in conducting a cautious interior assessment from a selected point of entry. This will be accomplished with assistance of a thermal imager as the crew gradually advances a charged hand line into the structure. Generally, firefighters involved in the assessment will eventually encounter the seat of the fire in one of five areas of the structure. For example, the fire may be located either:

- Near the initial point of entry (the A side for instance)

- in the concealed attic space

- in the area along the C wall

- in the center of the structure

- in the basement

Once the fire is located the assessing officer will make one of three safety based decisions. The decision is ultimately determined by assessing safety concerns with the existing hazards including but not limited to:

- The distance to the seat of the fire and concerns of adequate air supply in zero visibility conditions

- The amount of clutter in the structure and concerns of entanglement or entrapment in zero visibility conditions

- The amount of fire, heat and heavy smoke present and concerns of rapid fire spread

- Compromise of structural integrity and concerns of roof collapse in zero visibility conditions

Safety-Based Decisions

The interior assessment officer, in communication and coordination with command, will then decide on taking one of the following courses of action:

- Interior Attack from Initial Point of Entry: In this scenario, the officer feels comfortable with the short distance to the fire. The relatively clear path to the fire which is free of clutter or entanglement hazards and that the fire is of a manageable size involving only burning contents. (See Figure 1)

- Short Interior Attack from Different Side of Structure, Located Close to Seat of the Fire: In this situation the officer did not like the heavy clutter in the structure and high stacked merchandise with very narrow aisles. The distance to the seat of the fire was also too great to be able to safely advance to the rear of the structure, effectively attack the fire and still have enough breathing air to reach the safety of the exterior at the original point of entry. In this effort, forcible entry of adjacent existing enclosed windows or doors or exterior to interior wall breaching may be conducted to establish a safer means of access close to the seat of the fire. In other words, if safe, firefighters will make their own door when needed. (See Figure 2 and Figure 3)

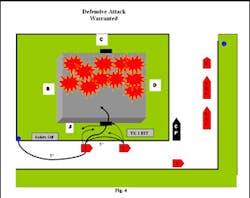

- Defensive Attack: An immediate withdrawal and initiation of a defensive attack is made. (See Figure 4)

In this scenario, the officer equipped with a thermal imager and accompanied by the crew, has observed a deteriorating condition which can not be safely managed, such as:

- A major portion of the structure is well involved

- The roof which may be constructed of trusses is significantly involved

- The fire involves a large amount of contents in which multiple handlines could not control.

Additional Guidelines

During the interior assessment the assessing officer will keep the distance advanced to a safe minimum. Safety, sector and command officers should be aware that the weight and friction involved in advancing a charged handline will inherently serve to maintain a safe minimum distance by preventing the crew from easily moving forward at a given point without the assistance of the back up companies.

In addition, the officer will withdraw in those instances when the seat of the fire cannot be located. In this case and when dealing with larger enclosed structures, such as those measuring 300 feet by 300 feet or greater in size, a second or third assessment from different points of entry may be conducted. However, depending on the amount of time elapsed and other factors, command may prefer to wait for the fire to flashover or to break through for use of a defensive attack.

Special thanks to: The National Fire Data Center; U.S. Fire Administration and The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Firefighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program

Related Articles

- Strategy and Tactics for Large Enclosed Structures - Part 1

- Strategy and Tactics for Large Enclosed Structures - Part 2

- Enclosed Structure Disorientation

Related Links:

- Enclosed Structure Standard Operating Guideline (SOG)

- U.S. Fire Adminstration Firefighter Fatalities Homepage

- United States Firefighter Disorientation Study 1979-2001

William R. Mora has dedicated 32 years to the San Antonio, TX, Fire Department as a firefighter, engineer, paramedic and training officer. Captain Mora is currently assigned to the firefighting division. He serves on technical advisory boards for the University of Kentucky, Lexington and has studied educational methodology and hazardous materials in depth at the National Fire Academy.

Captain William Mora is a fire consultant with an interest in firefighter safety, strategy and tactics, standard operating guideline development and firefighter disorientation. Captain Mora has advanced new firefighting terminology, tactics and concepts to help firefighters recognize, manage and avoid the risk at structure fires. He has been published on the topic of firefighter disorientation and enclosed structure tactics in Firehouse.com, Fire Chief Magazine, and Fire Engineering Magazine, as well as in the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation Everyone Goes Home Newsletter. He has given presentations on the prevention of firefighter disorientation for the Fire Department Instructors' Conference, Texas Volunteer Fire Departments and for the Maryland State Firemen's Association.

The firefighter disorientation problem has compelled Captain Mora to provide assistance to fire officials, safety educators, grant writers, and fire industry professionals with valuable researched information. He has been active in the effort to prevent firefighter disorientation and traumatic structural firefighter fatalities. Working towards that goal, Captain Mora conducted an analysis of 444 structural firefighter fatalities, identifying a large percentage of line-of-duty deaths occurring at enclosed structure fires where offensive strategies were used. He served as a participant at the 2004 and 2007 National Fallen Firefighters Foundation Life Safety Summits and currently serves as an advocate for the Everyone Goes Home Firefighter Life Safety Initiatives Program for the state of Texas. Captain Mora is the author of the United States Firefighter Disorientation Study 1979-2001 which appears in the United States Fire Administration's annual report: Firefighter Fatalities in the U.S. in 2003, 2004 and 2005. You can contact William by e-mail at: [email protected].