Reading the Fire: Developing Expertise

Reading the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) firefighter fatality reports or other documentation of incidents involving rapid fire progress, I ask myself: Would the individuals involved have taken the same course of action if they knew what the fire behavior would be?

Editors Note: To view more detailed images of the figures displayed on the right, please click on the links to each figure in the body of the article.

Surprises are sometimes OK on your birthday or during the holiday season, but are frequently a less enjoyable experience when they occur during structural firefighting operations. Reading the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) firefighter fatality reports or other documentation of incidents involving rapid fire progress, I ask myself: Would the individuals involved have taken the same course of action if they knew what the fire behavior would be? I think that this is unlikely.

In most of these cases, it is likely that neither the victims nor other key decision-makers recognized the likelihood or timing of rapid fire progress. Effective strategic and tactical decision-making is dependent on the ability to recognize current fire conditions and predict fire development and spread. Firefighting is often characterized as a battle. However, despite similarities, there is at least one fundamental difference between firefighting operations and warfare.

Because war is a clash between opposing human wills, the human dimension is central in war. . . War is shaped by human nature and is subject to the complexities, inconsistencies, and peculiarities which characterize human behavior (USMC, 1994, pp. 12-13).

Unlike warfare, firefighting operations are not a conflict between humans; firefighting is a human attempt to control a natural phenomenon. Civilians and at times even firefighters describe fire behavior as unpredictable. Nothing could be further from the truth. As a chemical and physical phenomenon, fire will behave the same way each time under the same conditions. It is the last part of this sentence that presents the problem when operating on the fireground. Scientists and fire protection engineers can control the conditions such as fuel load, ventilation profile and compartment configuration, resulting in consistent fire behavior under laboratory conditions. Firefighters operating at a structure fire have incomplete information about key factors influencing fire behavior and must quickly assess the situation and develop a plan of action.

Fire behavior is quite predictable, but limited information, pressure to make rapid decisions and our level of expertise limit our ability to do so under emergency conditions. How can firefighters improve their ability to recognize current conditions and predict fire behavior? It is useful to consider the difference between novices and experts.

Experience And Expertise

While this article focuses on fire behavior indicators, your real goal should be to develop expertise in reading the fire and predicting fire behavior. The words experience and expertise are often used without much thought about what they really mean.

Firefighters often conceptualize experience as years of service. However, this is only part of the picture. An experienced individual is "skilled or knowledgeable [has developed expertise] as the result of active participation or practice" (American Heritage College Dictionary, 2004, p. 429). Development of firefighting expertise requires opportunities for experience such as participation in training and actual firefighting operations as well as thinking about these experiences to draw out lessons learned. While the experiences themselves are significant, what is more significant is what the individual learns from that experience.

What is an expert? If an expert is someone who knows everything there is to know about a particular topic, it is likely that there are few if any experts. However, for our purposes an expert firefighter or fire officer is someone who has a high level of knowledge or skill. Experts and novices differ in a number of important ways (Bransford, Brown, and Cocking 1999; Klein 1999).

Table 1 illustrates how these differences may relate to expertise in reading the fire and predicting fire behavior.

Table 1. Implications of Expert/Novice Differences in Application of Fire Behavior Knowledge (PDF)

Adaptive Expertise

There are two different types of expertise. People who are consistently proficient at doing a specific task, such as stretching hoselines and throwing ladders have routine expertise. While this is important, it is not enough. Firefighters and fire officers also need the ability to apply their knowledge and skill under varied and changing circumstances. A fire officer who is proficient at sizing up a structure fire applies knowledge of fire behavior, building construction, and tactical operations under rapidly changing conditions. This is adaptive expertise. The important question is how do we develop this critical type of expertise.

Sir Eyre Massey Shaw, the first chief of the metropolitan London Fire Brigade wrote:

- In order to carry on your business properly, it is necessary for those who practice it to understand not only what they have to do, but why they have to do it...No fireman can ever be considered to have attained a real proficiency in his business until he has thoroughly mastered this combination of theory and practice (Shaw, 1876)

Shaw's observation is right on target. Development of adaptive expertise requires that firefighters and fire officers not only know what, but why. Safe and effective structural firefighting requires that firefighting skills be integrated with a solid knowledge of applied fire dynamics.

Fire Behavior Indicators - A Basic Framework

Firefighters can easily observe some fire behavior indicators, as illustrated in Figure 1. However, fire behavior indicators encompass a wide range of factors that firefighters may see, hear, or feel. Some factors can be are relatively unchanging (i.e. building construction) and others are quite dynamic, changing as the fire develops (i.e. smoke conditions and flames).

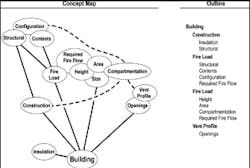

Figure 2 illustrates five categories of fire behavior indicators. Station Officer Shan Raffel of Queensland, Australia, Fire Rescue identifies smoke, air track, heat and flame as key indicators of fire behavior (Grimwood, Hartin, McDonough, & Raffel, 2005). Adding the building category allows integration of structural and contents factors to provide a more comprehensive set of key indicators.

Building: Many aspects of the building (and its contents) are of interest to firefighters. Building construction influences both fire development and potential for collapse. The occupancy and related contents are likely to have a major impact fire dynamics as well. Figure 3 outlines at least some of the building factors that may be relevant to fire behavior.

One of the key factors related to building factors is that they are present before the fire starts. Fire behavior prediction (at least in general terms) should be a key element in pre-incident planning. Look at the building and visualize how a fire would develop and spread based on key building factors (more on this in the next article).

Smoke: What does the smoke look like and where is it coming from? This indicator can be extremely useful in determining the location and extent of the fire. Smoke indicators may be visible on the exterior as well as inside the building. Don't forget that size-up and dynamic risk assessment continue after you have made entry!

Air Track: Related to smoke, air track is the movement of both smoke (generally out from the fire area) and air (generally in towards the fire area). Observation of air track starts from the exterior but becomes more critical when making entry. What does the air track look like at the door? Air track continues to be significant when you are working on the interior.

Heat: This includes a number of indirect indicators. Heat cannot be observed directly, but you can feel changes in temperature and may observe the effects of heat on the building and its contents. Remember that you are insulated from the fire environment, pay attention to temperature changes, but recognize the time lag between increased temperature and when you notice the difference. Visual clues such as crazing of glass and visible pyrolysis from fuel that has not yet ignited are also useful heat related indicators.

Flame: While one of the most obvious indicators, flame is listed last to reinforce that the other fire behavior indicators can often tell you more about conditions than being drawn to the flames like a moth. However, that said, location and appearance of visible flames can provide useful information which needs to be integrated with the other fire behavior indicators to get a good picture of conditions.

It is important not to focus in on a single indicator, but to look at all of the indicators together. Some will be more important than others under given circumstances.

Study and Discussion Questions

Building proficiency in predicting structural fire behavior requires developing skill in "reading the fire" as well as integration of your knowledge of fire dynamics. The first step in this process is to identify what to look for and the second is to deliberately practice this skill.

- Expand the basic concept map illustrated in Figure 2 by identifying the indicators in each category of FBI (Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame) that you might see, hear, or feel. A concept map can provide a graphic view of the key indicators and their relationships to one another. Keep in mind that there is more than one way to organize the factors. What is most important is that the concept map helps you make sense of things. However, if you feel more comfortable with making a list or outline of the indictors for each major category, this is another way to approach the task of building a more comprehensive view of the FBI. To provide a starting point, Figure 3 provides an example of one way that key building factors might be arranged on a concept map and using an outline.

- Practice your skill by looking for these indicators in photos (visit Firehouse.com Photo Stories on a regular basis), video, and at actual incidents.

Subsequent articles will examine each of these key groups of indicators in more detail. As you continue with your study of fire behavior, continue to refine and revise your concept map or lists of key indicators.

References

- American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. (2000).). Boston, MA: Houthton Mifflin.

- Bransford, J., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (Eds.). (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Downloaded April 9, 2006 from http://newton.nap.edu/html/howpeople1/index.html

- Grimwood, P., Hartin, E., McDonough, J., & Raffel, S. (in press). 3D firefighting: Techniques, tips, and tactics. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications.

- Shaw, E. (1876). Fire protection. London: Charles and Edwin Layton.

- United States Marine Corps (USMC). (1994). Warfighting. New York: Doubleday.

Related:

- Extreme Fire Behavior: Flashover

- Extreme Fire Behavior: Backdraft

- Extreme Fire Behavior: Smoke Explosion

Ed Hartin, M.S., EFO, MIFireE is a Battalion Chief with Gresham Fire and Emergency Services in Gresham, OR. Ed has a longstanding interest in fire behavior and has traveled internationally, studying fire behavior and firefighting best practices in Sweden, the UK, and Australia. Along with Paul Grimwood (UK), Shan Raffel and John McDonough (Australia), Ed co-authored 3D Firefighting: Techniques, Tips, and Tactics a text on compartment fire behavior and firefighting operations published by Fire Protection Publications.