Emergency Vehicle Response Near Misses

This is the 14th in a series of columns on emergency vehicle safety. The columns are a component of VFIS' "Operation Safe Arrival" initiative, aimed at heightening safety awareness and reducing the frequency and severity of accidents involving emergency vehicles.

The concept and understanding of a "near miss" is as varied as the number of personalities who work in emergency services. Two recent incidents that I am personally familiar with illustrate this point.

The first incident begins on a clear Sunday afternoon. We received a call from someone reporting chest pain, and I was driving our medic unit. Civilian drivers were actually doing what we would like every driver to do when approached by an emergency vehicle-slowing down and moving to the right, allowing us to continue on to the emergency. We were heading south down a two-lane highway with a posted speed limit of 55 mph. I approached an intersection controlled by a traffic light.

At this point, the road changed from two lanes into a three lane road with the far left lane a turning lane. Traffic was backed up in both through lanes. The turn lane was open, so I proceeded past the traffic which was stopped for the light. Because it is a one-way road, I had no concern about oncoming traffic.

At the light, a sizable hill sat to my left, and obstructed my view of traffic going east to west. Since the light was red, of course, I came to a complete stop. As we know, or at least do not want to admit, some drivers would have proceeded right through the red signal without stopping. Fortunately, it was good I came to a complete stop, because as I was slowing down to see if the traffic was clear, a car blew through the intersection from left to right. That driver did have the right of way (his speed was, by my estimation, excessive), but he did not see me and did not attempt to brake for me, even as my lights and sirens were activated. Had I driven through the light, someone would have been seriously hurt as he would have hit me at the driver's door.

My point on this - I went back to the hospital and was talking about this "near miss". One of my co-workers stated, rather smartly, "You probably were going too fast and were just lucky anyway." Wouldn't it have been nice to hear, "good job for taking your job seriously and stopping to avoid an accident"? The fact remains that this was a near miss incident.

During the second incident, I was the crew chief going to a respiratory arrest call, and my driver was doing a good job negotiating the traffic on a two-lane highway, that separated traffic by a double yellow line. As we approached a narrow bridge, he noticed a delivery truck approaching from the opposite direction.

Here is the dilemma - two large vehicles were approaching the same bridge, which is just barely large enough to allow two cars to pass. Both of us were traveling at about the same speed of 45 mph. My driver made a split second decision to accelerate and attempt to get over the bridge and onto a wider part of the roadway that allows a larger distance between the vehicles. Unfortunately, not everything goes as planned. Both vehicles passed on the bridge, and there was probably less than 1/10th of an inch between both vehicles. As they say, luck is simply a matter of inches or seconds. Another close call - you bet! The difference between the first scenario and the second was attitude.

On the first call, my instincts and training told me to slow down and evaluate the situation. This experience dictated that I stop at the intersection because the light was red, I had an obstructed view, and the 55 mph speed of the highway suggested I exercise caution. In the second situation, the attitude of "I can go faster and beat the other guy", or "I am an emergency vehicle, I have the right of way, and he must stop for me", dictated the driver's response. Either way, these examples were close calls.

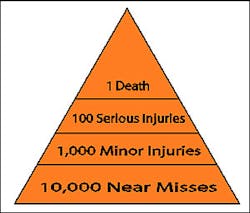

As drivers, we should be evaluated on the "close calls" or "near misses." It is in this evaluation process that an organization can determine how close "statistically" they are to having a serious or fatal crash. The theory depicted below illustrates this point, but a bit of an explanation is necessary. Looking at the pyramid, you see the top number is one. This represents a death or major property loss. For every one death that occurs, there are roughly 100 serious injuries or significant property loss. For every one death that occurs, there are roughly 1,000 treatable injuries or minor property loss. For every one death, there are roughly 10,000 near misses.

Most organizations wait until a death or serious injury occurs, and then decide to look at their program to avoid that specific event from ever occurring. Fact is, this event will probably never occur again, but the circumstances that caused the event will. Organizations need to be proactive and look at the near misses or close calls. By reducing the number of near misses, the statistical chance of having a serious or fatal event decreases. Why? Because by looking at the near misses, you begin to see the reason for both the near miss and potentially fatal incidents. attitude and education can begin to change these behaviors. It is in this change of behavior that drivers will begin to value their role, and understand that it is completely within their grasp to arrive safely or not.

Related Articles:

- Don't Become A Statistic

- Developing Procedures For Emergency Vehicle Response

- Safe Intersection Practices

- Responding In Personal Vehicles

- What's Your Speed Limit?

- Lights, Sirens...Action!

- Emergency Vehicle Driver Training: More Important Than Ever

- Selecting Emergency Vehicle Drivers

- Taking Control of Traffic - Electronically

- Emergency Vehicles and Intersections: Educating the Public

- Event Data Recorders - The "Black Box" for Safer Response

- Emergency Vehicle Driving and Traffic Preemption

- Does Motivation Affect Firefighters?

- VFIS Operation Safe Arrival Website