"I Survived"

I dropped dead on Friday, Oct. 29, 2004, at approximately 1409 hours while working as the incident commander at an apartment fire in West Seattle. Only by the grace of God, quick work by Seattle firefighter/EMTs and firefighter/paramedics, and the miracles of modern medicine am I alive today to talk about it.

On that date, I was a 53-year-old battalion chief with 30 years' experience as a professional firefighter. Just after eating lunch and then smoking a cigarette on the back porch of Station 11 in the southern part of the Seventh Battalion, the bells hit. I figured it was an aid call for Engine 11 until I heard the tones and dispatch for a structure fire a few blocks away.

I felt a slight, but sharp pain streak across the top of my chest from shoulder to shoulder just below the level of my collarbone while driving to the alarm location. I shrugged my shoulders and it went away, just as it had numerous times before when I would get a quick shot of adrenalin or be working physically hard. "I've got to quit smoking," I thought, as I once again dismissed the pain as an upper airway or musculo-skeletal problem.

I arrived at the location the same time as Engine 11, gave an initial report of no sign of fire or smoke from a newer two-story apartment building and established command with 11's investigating. The lieutenant and tailboard firefighter from 11's stretched a 200-foot pre-connected 1.5-inch line to the front door of the apartment located up a stairway and above a grade-level garage. Black smoke lazily fell out of the unit as soon as they kicked in the locked front door. I reported to our Fire Alarm Center that we now had smoke showing and ordered Engine 37 to lay a supply and a backup line to 11's. Other orders followed, just like for any room-and-contents apartment fire.

After a short while, I got impatient with the lack of progress underway and hollered at 11's lieutenant, asking what was taking so long. The reply was that the hallway was blocked by something and the hose was kinked. So I walked up a few steps, unkinked the hose and got a small whiff of smoke. I remember that it smelled unusually bad and acrid, but didn't think much more about it. As it turns out, it was cold smoke from a fire that had been smoldering for quite a while in a newer, tightly sealed structure. Engine 11 was having a difficult time locating the seat of the fire because a large couch was on end in the hallway and blocking the door to a back bedroom where the fire originated.

A little more time went by and most of the response had arrived at the location, although none of the other command officers had yet arrived at the command post. Ladder 11 broke out a window in the fire room and established positive-pressure ventilation. Firefighter/Paramedic Jonny Layefsky yelled to me that we just about had the fire tapped, as light-colored smoke and steam came blasting out of that ventilation exit point. I heard a muffled radio report and responded that it was unreadable. That's when everything started to get crazy and my life was to dramatically change in an instant.

I don't know if the following events happened over the course of a few seconds or in a nano-second. I started to feel confused and wondered if I was running the fire correctly. Then my vision narrowed; it came down from the top and up from the bottom and all I saw were the faces and helmets of the firefighters standing near me. I thought to myself, "Oh "expletive," something is really wrong here."

Then all sound went away and I was deaf, even though a gasoline-powered fan was operating in front of me and Engine 11's apparatus was pumping behind me. Then it was like somebody turned off the TV and everything went black, the blackest black I had ever seen. And that was it. That was all I saw, heard and felt. No pain, no anxiety, none of my life passed in front of my eyes, nothing.

As the firefighters on scene describe it, I had the radio up to my face and then stumbled a few steps backward. I fell flat on my back onto a small grassy strip between the concrete sidewalk and curb. Layefsky was standing between two parked cars next to the curb and I landed right in front of him. Brian Paterik, the driver on Engine 37, was about 10 steps away when he heard the thud. It was so loud that he thought someone had jumped from a second-floor window. Rick Colombi, the Engine 36 driver, was talking to me when I dropped like a rock. He said it all happened in a nano-second, my eyes rolled back in my head, I collapsed, my face turned blue and I had the look of a dead man.

My heart had gone into ventricular fibrillation and I was in cardiac arrest. I was clinically dead with no pulse and no respirations. Layefsky's partner, Jeff Jinka, made a mad dash to the Medic One unit to retrieve the medic kits, while the firefighter/EMTs got the aid kit, ventilation kit and defibrillator from Engine 11. Layefsky directed the show and the firefighters started CPR immediately and hooked me up to the defibrillator.

I appreciate the crews not cutting off my foul-weather coat, as it was a battalion chief promotion gift from Recruit Class 86 and the members of Training Division in November 2001. I'm also glad they didn't cut off my uniform shirt, even though all the buttons were gone when I got it back. As I understand things, it is also good that the fire was just about extinguished because everyone except 11's was now outside the fire building tending to me like a flock of seagulls over a fresh pile of fish.

As amazing as it may sound, these firefighter/EMTs and paramedics took care of business and gave my life back to me all in the course of about four minutes! This is a tribute to the organization, training and dedication of all the people associated with Medic One; Doctors Cobb and Copass, the physicians, nurses, technicians and attendants in the emergency room, the Seattle firefighter/paramedics and Seattle firefighters, all of whom are EMT certified.

After a couple of minutes of CPR, the defibrillator analyzed my condition and recommended, "Shock Advised." It built up an electrical charge and the "Shock" button was depressed. I received one shock, which I did not feel. The EKG went from VF to a more-or-less normal rhythm.

From the moment of seeing the blackest-black I had ever seen, the next thing I remember was feeling a blast of cool, clean, crisp air being forced into my mouth and lungs. It felt terrific. I recall thinking, "Man, this is really, really refreshing!" Then another blast came rushing into my lungs and I'll bet I was smiling because it felt so good. I opened my eyes and saw all of the firefighters looking down at me and the edge of the bag mask over my nose. Somehow, I knew that I had just had the big one.

Tommy Nelson, a giant of a man working on 36's that day, was yelling at me to wake up and said that he heard me say that I had the big one. I asked someone else what happened and he said I collapsed, but that I would be OK. Then I raised my head and saw Rob Jacobowitz, a young firefighter who was a member of Recruit Class 86 and someone I had been teasing mercilessly since he got off probation. I took a special liking to him for some goofy reason and I think he also gets a kick out of all the attention I give him. I said, "Is that you, Jacobowitz?" And he replied, "Yes." Then I put my head back down and cracked wise saying, "Oh "expletive" me." He looked up at Layefsky and said, "He's got his eyes open, he's talking and he's coming around, I mean he is really coming around!"

Layefsky looked down at me and said, "OK, Dave, if you can talk, then you can breathe. So start breathing or I'll tube you, and you know me, I'll tube you!" That's when I thought to myself, "Oh man, now I have to go to work and start breathing on my own." I can't believe that I actually thought breathing was work, but I did. It took me a few tries before I figured it out and started breathing on my own. Fortunately, I've been able to keep it up ever since.

I remember the crews putting me on a backboard and onto the stretcher, then loading me into the medic unit. I had my eyes closed most of the time because I was very tired. At one point, I was asked to hold my hands together and I worked to accomplish it, as they were unusually weak. I felt lightheaded and slightly dizzy, although fully aware of my surroundings and what was happening around me. I was alert, oriented and perfectly capable of passing on information needed for the medical report, a Form 20-B. I was in no pain and had no discomfort as a result of CPR or the defibrillator shock.

For a short time, a couple of minutes or just a few seconds, I cannot remember, it was quiet and I was alone with my thoughts. I prayed to God that if He was going to take me this day to please forgive my sins because I really wanted to go to heaven. On the other hand, I continued, since You let me be resuscitated, maybe You are going to let me live. If so, You let me know what You want me to do with this life of mine and consider it done!

Jinka drove the medic unit and Layefsky was accompanied in the back by Tony (Lasagna) Leseigne, who was riding Aid 14 that day. The other member of Aid 14, Mike Milner, drove that rig up to Harborview Medical Center (HMC) to meet up with Leseigne. I felt at ease and comfortable knowing that I was in good hands.

We arrived at Harborview, our regional trauma center and home to Medic One, and I was wheeled into the emergency room. Having ridden Aid 2 and Aid 25 in years past, I knew the drill. A bunch of doctors, nurses and technicians gathered around me, all seemingly talking at the same time and carrying on like a gaggle of geese. They had me stripped down, wired for sound, bloods drawn, X-rayed and you name it in no time. These people really know what they are doing, they are some of the best of the best.

Assistant Chief of Operations A.D. Vickery was waiting for me in the ER. I asked him to contact my buddies Lieutenant Bob Myers and Captain Preston Bhang and have one or both of them pick up my wife, Janna. I gave him Janna's cell phone number and asked him to call her. All he calmly said to her was that I collapsed at a fire and that I was OK, and he had our friend Bob Myers on his way over to pick her up.

She figured I just got smoked up a little and didn't get too terribly shook up. As it turns out, this was a very good thing. Had she known right off that I had gone into cardiac arrest and was given CPR, as she found out later at the hospital, she may have gotten into a wreck driving from where she was back home to where Bob planned to pick her up. At the hospital, she had SFD friends and doctors to support her when she was told exactly what happened to me.

After the ER examination and preliminary work up, I was wheeled down to the basement and the cath lab. An angiogram was performed and showed that I had some clogged coronary arteries. The diagnosis was simple, I was to undergo a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), otherwise known as open heart surgery.

On the way back up to the ER, the nurse asked me if I was ready to see the crowd that was waiting for me. My wife and I have a large blended family of 13 children, with an assortment of sons-in-law, a daughter-in-law and 12 grandchildren. Two sons in their 20s popped out from a small waiting room when they saw me being wheeled down the hall. One, an electrician, kissed me on the forehead a couple of times and the other, a football player, looked like he was ready to cry any minute. They didn't know where everyone else was hanging out, which happened to be the paramedic quarters near the emergency room area, so they followed us.

The nurse wheeled me into the little ER area where I had been and then closed the curtain. I was alone for just a moment and then my wife came in. It was special that everyone allowed the two of us to have a few private minutes together. I can't remember if I said, "I'm sorry," or, "I really did it this time." I don't do crying, but I felt my eyes well up and I could see tears falling down her cheeks. It was great to be alive and the magnitude of what happened was finally starting to sink in. We hugged and kissed and just sort of looked at each other. Then she asked if I was ready for the crowd. "I am if you are," was my reply.

She opened the curtain and in they came, sons and daughters, a couple of older grandkids, firefighters of all ranks, paramedics, Chief of the Fire Department Gregory Dean, the mayor of Seattle and so on. All we needed was a keg and some chips! A much-better scenario than those times when a firefighter is badly busted up and just hanging by a thread.

Things cleared out after a short while and I was taken to a room in the cardiac intensive care unit. It was explained that I would be transferred to the University of Washington Medical Center, where I would undergo the heart bypass surgery. At 1 o'clock in the morning, Firefighter/Paramedics Chris Robinson and Matt Anderson transferred my wife and me to the UW Medical Center. I would be there until the following Friday.

The next day, Saturday, I was feeling great. I even told my wife and the nurse that I felt guilty taking up a bed in the cardiac intensive care unit. The nurse gently patted me on the shoulder and said that she was glad the medicine was working and that I was exactly where I needed to be. A while later, Dr. Gabriel Aldea walked in. He would be the surgeon leading his team as they performed open heart surgery on me. He said that his schedule was really tight for Monday and Tuesday, so they would be performing the surgery on me at 9 o'clock Sunday morning, Halloween. He didn't want me to wait until Wednesday.

That night we were to change from Daylight Savings Time to Pacific Standard Time; turn the clocks back an hour. I had fallen asleep early and woke up Sunday morning around 5:30. Our oldest son walked into the room just about 6 o'clock and woke up his Mom with a big, "Good morning!" He thought it was 7. After a laugh and the realization that he was an hour off, he took his Mom down to the cafeteria for breakfast. That left me alone with my thoughts.

For the first time, I started to get a little anxious. Before long, thankfully, Bob Myers and his wife, Laurean, a couple of other friends and our children showed up. All of my fears disappeared in an instant. The support I was receiving was unbelievable. I was now fearless and realized that I had placed everything into God's hands and all would be good. A nurse came by at 8:45 and we were off to the basement and surgery. I had not a fear in the world.

I was returned to intensive care a few hours later. The surgery was a complete success. Dr. Aldea and his team did a four-way bypass. One coronary artery was 100% blocked and the other three clogged in the 80%-90% ranges. A mammary artery from the left side of my chest was used for one graft and three sections of vein were harvested from my right leg for the others.

Janna took one look at me and had to sit down. I had tubes sticking out of my neck, two tubes coming out of my chest, six or more intravenous bags hooked up to my arms, lots of wires connected to sticky pads all over me and a catheter for urine output. Asked what my pain level was on a scale of one to 10 with 10 being the most intense, I kept flashing five fingers in an attempt to signal a 9.5. Thank goodness for drugs, as I have no recollection of that pain.

The intubation tube was removed after I was able to take seven or more breaths per minute. The rest of that day is kind of a blur. I would fall asleep and then halfway wake up, normal for the surgery just experienced. The nurses gave me a pillow and told me to hug it tightly whenever I was about to cough or sneeze. I never let it leave my sight! Each day after I kept feeling better.

I was relocated to a regular room late Monday or early Tuesday and visitors were allowed. That was great. All of our children and grandchildren and lots of folks stopped by and the firefighters, of course, kept things lively.

On Thursday, Dr. Jeannie Poole and her team installed an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) inside my upper left chest. Should my heart ever decide to go back into ventricular fibrillation again, the AICD will fire off an electrical charge to convert the heart back to a normal rhythm. Fortunately, it has yet to fire. Every four months, I go in for a checkup and a special computer is used to read the output from the little $50,000 titanium machine. When it says that the battery is running low, I go in for another surgery and have it replaced. The wires run directly to my heart, so all they do is unplug the old unit and plug in the new one.

The next evening, Friday, Janna was allowed to take me home. It felt good to be home and weird at the same time. I knew that my life had been changed forever and wondered how well I would adjust. My worries were unfounded. Everything has worked out just fine. I quit smoking, of course. I started working out in a gym four days a week with a routine selected for me by a physical fitness professional. On the fifth day, I ride a bicycle five miles and try to walk a couple of miles on the sixth day. I'm still working on the heart-healthy diet, but have changed my eating habits nonetheless.

Prior to 1409 hours on Oct. 29, 2004, I was the perfect "before" picture for physical fitness and heart-healthy living. I'm the one who might have said, "Quit smoking? I'm a firefighter, smoke is my business!" Or, while getting ready to bite into a bacon-cheddar cheeseburger, might say something like, "Mmm, a cardiovascular dream come true." I have said things like that and it took me 53 years to figure out that I was dead wrong. It took a good whack in the middle of the chest to wake me up, but I got the message loud and clear.

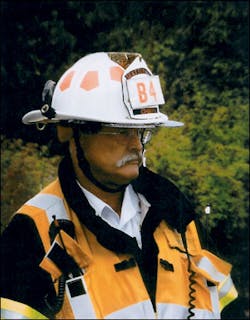

Dave Jacobs is a battalion chief and EMT for the City of Seattle Fire Department. He is a career firefighter with over 30 years of fire service experience. Jacobs will be a keynote speaker at Firehouse World 2006 in San Diego, Feb. 19-23.