From The Officer’s Seat: The Rapid Intervention Rope Bag

The activities of a rapid intervention team prior to a “Mayday” are widely defined, dependent on individual department standard operating procedures (SOPs). However, once a true emergency exists on the fireground, the rapid intervention team’s task is clear: to remove the downed firefighter as quickly as possible.

Let’s make two assumptions: that a firefighter in full protective gear may weigh in excess of 300 pounds, and that a “Mayday” on the fireground will occur at the worst possible time – when the incident commander has changed from an offensive to defensive mode, when members’ air supplies are depleted and their strength is exhausted.

While now required by the “2 in/2 out” rule, it is unreasonable to expect that six fresh firefighters will be standing at the ready at every structure fire. Therefore, we must be prepared for the worst and train to that level.

Proper training will prepare us to move a downed firefighter rapidly. While many in the fire service would rather “muscle” the firefighter, instead of taking extra effort to use ropes and pulleys, using a mechanical advantage will make the work easier. Sadly, there are case histories in which strength was not sufficient to remove a firefighter (who eventually succumbed) – time is the most critical factor in a firefighter rescue.

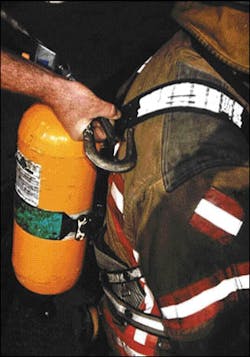

This article highlights a rapid intervention rope bag that is both quick and easy to use. The bag contains 90 feet of half-inch kernmantle rope, a pulley, two large hooks and a carabiner. The hooks, taken from old life belts, can be opened with one hand. (The goal is to be able to perform this rescue as quickly as possible under adverse conditions.)

Several presumptions must be made in order to appreciate the benefits of this rope bag. First, expect a downed firefighter to be wearing self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), since this rescue/removal will most likely be occurring from inside a fire building. Second, it is crucial to the rescue operation’s success that another firefighter be able to access the downed member to attach the hook onto his SCBA.

These rapid-rescue techniques require a partner to quickly place the hook onto the downed firefighter and guide him out to safety. These evolutions do not consider any cervical spine injuries. Packaging a firefighter with suspected neck injuries requires additional time and equipment. These rescues may take place in zero visibility, hence the need to keep them simple.

There is no right or wrong way to rapidly remove a downed firefighter from a building. What is important is that we can do it no matter what the conditions are. It is hoped that this article offers you another way to help us take care of each other.

In this first lesson, we will describe a method to remove a downed firefighter through a window. To use the bag, the standing end of the rope needs to be anchored to a high point outside the window. This evolution will work with ground ladders for first-, second- or third-floor scenarios. Any floor higher will require the use of an aerial device. For most departments, a 24-foot extension ladder will suffice for first and second floor removals.

Hook the standing end of the rope to the top rung (point A in the accompanying diagram). Then, the outside rescuer must pass the hook/pulley combination through the second and third rungs to the inside member (point B).

Inside, a lone rescuer takes time to reposition the SCBA waistband so that it is passed between the legs and buckled in the crotch area. This turns the SCBA harness into a sort of full-body harness. This requires practice and thorough familiarity with all SCBA, especially if you are the rapid intervention team for a neighboring department.

At this time, the hook/pulley is used to grab the downed firefighter at the shoulder straps behind his head (point C). With the rescuer on the ladder acting as coordinator, the troops on the ground are directed to pull on the rope (point D). The lone inside rescuer merely guides the downed firefighter toward the window so that the SCBA (of the victim) is against the outside wall.

With a 2:1 mechanical advantage on the line, there is a greater chance for success if not enough members are available outside and you are forced to use untrained civilians. (If civilians are used to successfully rescue a downed firefighter, is this a bad thing?) The inside rescuer straddles the downed firefighter, maintaining the victim’s position of his back toward the outside wall. As he is lifted off the floor, the inside rescuer grabs both shoulder straps in the front of the downed firefighter and leans back towards the center of the room. This helps clear the top of the SCBA bottle as he goes up and over the windowsill.

At this point, we are looking to get the center of gravity of the downed firefighter to the window only enough to “push him out.” The outside teams have a hold and he will not drop, as the rungs of the ladder create enough friction to make lowering an easy task. With practice, this evolution can be accomplished swiftly and in zero visibility.

There is no doubt that the safety critics will find fault with this setup. The muscular members of the fire service debunk this methodology as too time consuming – “If you are not strong enough to lift/drag your partner, then you don’t belong in the fire service” is a valiant and noble ideal; too bad it is just not realistic. If we train for the worst-case scenario, then we will be ready for whatever we face.

In the name of firefighter rescue, we should be prepared for the time when we are under-manned; everyone is on their second SCBA bottle; exhausted; wet, and the conditions are worsening. Our next installment will describe using the rope bag to remove downed firefighters through a hole in the floor.