FHExpo18: Preventing Harassment & Discrimination in the Fire Service

The fire service is a high-risk profession. No one questions that. But during their Firehouse Expo 2018 session “Preventing Harassment and Discrimination in the Fire Service,” Chief Brian Cummings and Lt. Eric Rosoff underscored that the risks firefighters face go well beyond the fireground or rescue scene and, in fact, firefighters are much more likely to get fired from a harassment- or discrimination-related issue than die in the line of duty.

Cummings, who served for 34 years with the Los Angeles Fire Department, said there is a harassment/discrimination-based lawsuit filed, on average, every 12 weeks against a fire service agency, and that the frequency is increasing due to some of the recent empowerment movements and the increased scrutiny on station behavior. Rosoff, who served as a lieutenant with the Burbank, CA, Fire Department, added that most lawsuits come from within the department, initiated by members who have been on the job for less than six year. Firefighters can no longer assume that certain behavior is just accepted as fun, harmless antics around the station or that it won’t get beyond their unit, he said.

Cummings said the fire service is such a homogenous group—primarily white men—that it’s ripe for these types of conflict. Further, certain types of bad behavior have been tolerated for such a long time that there’s a “group think” mentality that it’s OK. And that’s where some of the confusion rests: There can be a triggering event, but it’s commonly an aggregate of events—“the steady drip”—that ultimately creates a hostile work environment. What’s worse: Supervisors are typically often in the behavior or know about the behavior, but fail to take action.

Rosoff and Cummings shared several definitions that are important to understand when discussing workplace discrimination and harassment:

- Protected classes: A group with common characteristics who are legally protected from employment discrimination based on that characteristic. These characteristics include race/color; genetic information; religion; sex; gender, gender identity/expression, sexual orientation; national origin, ancestry; mental and physical disability or medical condition; age (over 40); pregnancy; and martial status.

- Harassment: Offensive conduct related to a protected class, specifically, behaviors that a reasonable person would consider intimidating, hostile or abusive, and enduring the offensive conduct becomes a condition of continued employment, or the conduct is severe, unwanted or pervasive—the “steady drip” that constitutes a hostile work environment. (Note: Petty slights, annoyances and isolated incidents, unless serious, will not rise to the level of illegality, but it must still be addressed before they become pervasive.)

- Sexual harassment: Requests for sexual favors (quid pro quo); verbal, visual or physical conduct of a sexual nature; unwanted, severe or pervasive behavior that creates a hostile work environment.

- Third-party harassment: Unintended recipients are subject to harassment as well—a common situation in the fire service, as friends on the job may have long-standing nicknames for each other.

- Abusive conduct: Repeated hostile, intimidating and/or offensive verbal abuse; sabotage or undermining a coworker.

- Discrimination: The unjust or prejudicial treatment of employees, by an employer, based on their “protected class” status. This can involve promotions, pay, transfers and/or training.

- Retaliation: This is the tangible impact of the bad behavior—a material loss or negative change in the terms of conditions of employment following filing a complaint or testifying/assisting with a complaint.

- Hostile work environment: Pervasive unwelcome or offensive actions, which cause one or more employees to feel uncomfortable, scared or intimidated in their place of employment.

Cummings and Rosoff explained that they wanted to consider how the training on the operations side of public safety applies to the personnel world, where most people find themselves in trouble. Similar to operations training, they outlined the following steps: Recognize the danger, set clear expectations, train to develop reflex response, and hold people accountable. The problem is that most of us don’t train on the personnel issues, only operations.

Reporting is also key, they said. Talk to the offender, tell any supervisor, chief officer or someone from HR, the Department of Fair Employment & Housing (DFEH), or the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Supervisors are expected to act, and often a simple “knock it off” can quash an issue before it evolves into a pervasive action.

“Our folks have to be encouraged to step up and say ‘stop it,’” Rosoff said, adding that firefighters don’t stop being heroes when they aren’t fighting fires—they can make a difference at the station, too.

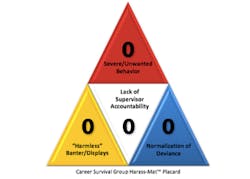

Cummings and Rosoff introduced a method for departments to use to gauge the existence of a hostile work environment: Harass-Mat Training. Similar to the placards used to identify hazardous materials, a harass-mat graphic (pictured at right) can be used as a scoring system to identify the impact of behavior on the work environment. Specifically, give a score of 0–3 for each of the segments pictured:

- 0 – Not occurring

- 1 – Occasionally occurs/quickly corrected

- 2 – Occasionally occurs/rarely corrected

- 3 – Regularly occurs/rarely or never corrected

After assigning a score to each of the four placard segments, the final tally will reveal the workplace rating:

- 0–2 – Professional work environment

- 3–5 – Arguably a hostile work environment

- 6–12 – Hostile work environment

Cummings underscored that all of this training rests of the front-line supervisors, who set the tone that becomes informal “policy” for crews. “We can’t overstate the importance of that role,” he said. Rosoff added that company officers must set clear expectations, that they can often fix the problem well before it gets bigger, and it’s imperative for them to document actions, complaints, etc.

In the end, stopping the problem before it becomes a massive HR nightmare or lawsuit necessitates members holding each other accountable.

For additional information, visit Rosoff and Cummings’ company Career Survival Group.

About the Author

Janelle Foskett

Janelle Foskett served as editorial director of Firehouse Magazine and Firehouse.com, overseeing the editorial operations for the print edition along with working closely with the Web team.