The Rapid Intervention Reality of Your Department - Part 2

The first installment of this series (January 2011) discussed preliminary items that must be understood to have a successful rapid intervention team (RIT) on the fireground. The next question that must be asked is this: What is the true rapid intervention capability for your fire department?

An in-depth assessment using the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1407 Standard for Training Fire Service Rapid Intervention Crews can help us answer that question. To have a successful training program and function on the fireground when it comes to rapid intervention, as a minimum a fire department should be covering 18 points that we will begin discussing in this column.

Point 1 – Our department has a plan that all members understand and have been trained on for calling a Mayday on the fireground.

Does your department have a rapid intervention policy or operating guideline in place? Even more important, does every member understand it? If your department does not have a policy, many resources are available to help you develop one. Is there a policy for calling for help and is everyone trained on how to do so if the need arises on the fireground? LUNAR is an acronym that has been successful when calling for help:

LOCATION – Where is the distressed firefighter?

UNIT – What unit on the fireground is the firefighter assigned to?

NAME – What is the name of the firefighter who is in trouble or missing?

AIR STATUS – How much air does the firefighter have?

RESOURCES – What is the problem the firefighter is experiencing and what is needed to help?

Many instructors use the acronym LIP to further simplify the call for help:

LOCATION – What is your location?

IDENTIFICATION – Who are you?

PROBLEM – What is your problem?

No matter what acronym is used, the important point is that your department has a procedure and everyone from the chief to the greenest rookie understands the process. Even more important, however, is that every member is trained to recognize trouble and to call for help at the earliest point to provide the best chance of survival.

Point 2 – My department has the proper rescue equipment to fulfill rapid intervention responsibilities on scene and does not have to call for it after a Mayday is declared.

Does your department have the resources to staff a rapid intervention team on the fireground? Is the function an automatic pre-designated assignment? Remember; when a RIT is placed into action, the resources better be in place to back up that RIT. It has been common practice that many departments will escalate the alarm by two levels if a RIT is activated. None of us, with the exception of the largest cities, have the capability to properly fill this role by ourselves. If not done so already, break down the fences and get your neighboring departments to help and get that help rolling early in the response – it can always be returned if not needed.

Point 3 – If a Mayday is called, we have a plan to provide strong command presence in the rescue efforts while maintaining discipline and control of fire suppression measures.

Does your command team have a plan if a Mayday is called? It is important that discipline is maintained to ensure suppression efforts continue during a Mayday situation, for they may be what is keeping the downed firefighter alive.

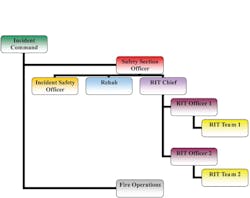

Managing a Mayday requires the incident commander to get help. Everyone’s focus is going to be on the rescue effort. As the suppression efforts continue, a RIT is deploying into a hazardous condition and must be closely managed. A strong command presence is needed to maintain their safety. For this reason, it is suggested that a second command-team person control the RIT deployment and the incident commander remain in control of the suppression efforts. This concept has been used successfully by departments with a command-team member designated as a safety section officer. This person, once in place, will be responsible for the incident safety officers, accountability and rehab, but the ultimate focus is to command the RIT functions if a Mayday occurs.

In addition, an officer should be assigned to the role of RIT chief. This additional officer provides another command layer at the operational level and provides direct accountability for a deployed RIT. Filling this role allows the company officer assigned to the RIT the ability to function as part of their crew and focus directly on the rescue effort being undertaken. This layer also helps in preventing freelancing from occurring in the rescue efforts (Figure 1).

The RIT chief position does not necessarily have to be filled by a chief officer, but it requires a disciplined individual who is knowledgeable and can demonstrate a strong leadership presence. This position will directly support the RIT operation and provide several advantages in handling a fireground Mayday. One of the advantages of its implementation is that it decentralizes command which reduces confusion, redundant or conflicting orders and radio traffic. Other advantages directly related include:

• The presence of a RIT chief lets the RIT officer focus on the rescue efforts

• The position supports the RIT with manpower, equipment and special needs

• Direct management controls freelancing in the rescue effort

• They provide direct accountability for the deployed RIT

• A RIT chief provides a set of eyes to the RIT to constantly monitor fireground conditions

• They ensure that the backup RITs are in place and briefed about the rescue plan

All communications from the RIT officer should be directed to the RIT operations chief, who will be providing resources and making decisions related to the rescue. The RIT operations chief should also be mobile to a degree from the interior to the RIT’s point of entry to get a true indication of the operation taking place in the rescue effort. If they must be committed solely to the interior, it is important that a second RIT chief be placed into action on the exterior to monitor conditions.

The RIT chief and RIT officer should work together to make certain that all necessary tasks and considerations are addressed prior to a Mayday. A RIT chief/RIT officer checklist can prove beneficial in this situation. Checklists and forms can provide training documents prior to an incident or spark the memory during an actual incident. Operating in a Mayday situation is a very-low-frequency and ultra-hazardous event – why would we not want our people operating in key positions to have the tools they need to be successful?

Checklists do not put out fires and solve problems, but they aid the incident commander, especially if that person is alone in first few minutes of a working incident. Tactical worksheets need to be designed to coincide with department policies and the way incident commanders have been trained (Figure 2).

Point 4 – My department members understand their role and are able to practice continual ongoing risk assessment when functioning as a RIT on the fireground.

Does your department have a policy covering risk/benefit analysis taking place on the fireground? Risk/benefit analysis is something that must take place every time that we are going to commit our people to immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) conditions. It lays the foundation for every decision that we will make at that incident. NFPA 1500, 1521 and 1561 all require every fire department to have a policy on risk in place to be followed. This type of policy does not have to be lengthy and extensive. It can be very simple; it just needs to be understood by the members of your department.

One important principle of risk analysis that is often overlooked is the concept of fire flow on the fireground. In a nutshell, if we have enough water to meet the required fire flow, we can generally commit members to interior operations. This is a general assumption that does not take into consideration other factors, such as building construction and occupancy. If we cannot meet the fire flow, then we should be in a defensive posture. (If your gut is telling you something does not seem right, don’t second-guess yourself.) Resources can always be recommitted if an error on the side of safety is made, but if you decide that you should be defensive even one second too late, you can never get back what is lost in that second (Figure 3).

Situational awareness, or the ability to have perception mirror the actual environment, is another concept that must be taken into consideration. Many factors affect our situational awareness:

• Insufficient communication – Failure to advise others of hazardous conditions or provide progress reports is a consistent item for consideration when analyzing why things go wrong

• Fatigue and stress – Our minds just do not function at the same high level when faced with fatigue and stress

• Task overload – Focus is lost and we become more concerned with quantity rather than quality

• Task underload – Complacency sets in and focus is lost

• Group mindset and philosophy – We do not like to admit that we cannot do something or risk having another company show us up on the fireground (we have to get over that mentality); yes we have a job to do and the public has high expectations, but our families expect us to return home after our tour of duty.

• Degrading conditions – How many times does this lure us deeper? Taking the time to fully realize what we are dealing with is critical (Figures 4 and 5)

Point 5 – The RIT is permitted to operate in a proactive manner.

What does the rapid intervention team do on your fireground? Are the members actively involved in making the scene safe or are they staged in a position that makes them useless? My next column will address working proactively on the fireground.

About the Author

Jeffrey Pindelski

JEFFREY PINDELSKI is the Downers Grove, IL, Fire Department Chief (Ret.) and has been a student of the fire service for more than 30 years. He served as a chief officer for more than 15 years of his career, during which time he directly managed every aspect of the fire department at one time or another. Pindelski holds a master's degree in Public Safety Administration from Lewis University and earned a Graduate Certificate in Managerial Leadership and a bachelor's degree from Western Illinois University. He is the co-author of "R.I.C.O.- Rapid Intervention Company Operations" and was a revising author of the third edition of "Firefighter's Handbook." Pindelski presented at numerous fire service conferences and had more than 55 articles published in trade journals on various fire service-related topics. He is a recipient of Illinois' Firefighting Medal of Valor.