Implementing a Behavioral Health Program

A Death in the Family

In the Fall of 2017, a member of the Dallas Fire-Rescue Department (DFR) died by suicide. Earlier that year, the firefighter had been arrested for driving under the influence (DUI) and as a result faced disciplinary action. When the department learned of a second alcohol-related issue later the same year, and pending the outcome of the investigation, additional disciplinary action led to the firefighter being placed on administrative leave. Upon learning that he was being placed on leave and being sent home, the firefighter assumed he would be fired. After leaving the station, he went home, sent a text to his family and shot himself.

The firefighter had several events occurring in his life simultaneously that if shared with his DFR family might have raised enough flags that would have been identified as warning signs. However, the small confidences the firefighter shared individually with his crew were made with a promise of secrecy. His colleagues respected his wishes and in doing so did not talk with each other about the challenges he was facing. The firefighter did not share that his efforts with the City’s Employee Assistance Program were not felt to be helpful and that he had opted to seek private professional counseling services prior to the second offense.

Following his death, there was a significant outpouring of love and compassion from within the department and the city. Soon after his funeral, members of the DFR Executive Team (Fire Chief and five Assistant Chiefs) met to discuss the suicide. This was the third firefighter suicide in the department in just the past five years. When the Chief asked what had been done following the previous two suicides, the team reported that this was the first time the Executive Team had met to discuss the topic of suicide among first responders.

They sat and looked at each other for a few minutes—likely in shock over this revelation—and then began to discuss potential next steps to address preventing suicide as well as overall behavioral health issues in the fire service. That day, Dallas Fire-Rescue began a year-long journey to move the department forward and address long-held cultural issues that have changed the way the department provides support and advocacy for members who were dealing with emotional health challenges in their lives.

For most of the department’s history, disciplinary infractions had been treated punitively, rather than viewing certain infractions as symptoms of underlying behavioral health issues, including substance use disorders. In an attempt to promote cultural change in the department, there was general agreement that we needed to transition from a “gotcha” mentality to a more progressive, rehabilitative model.

The department recognized that first responders were at higher risk of using unhealthy coping mechanisms to manage the stress of their work. We sought to develop a model wherein members were held accountable while also supporting their return to duty in a safe and compassionate manner while giving them the environment and tools to help them heal, grow and thrive.

The Gap Analysis

A process to identify “gaps” in the policies and practices regarding behavioral health in the department was initiated. Bi-weekly meetings were held with representatives, including:

- The Executive Team

- Representatives of the three firefighters’ associations (IAFF Local 58, the Black Firefighters Association, and the Dallas Hispanic Firefighters Association)

- Department Chaplains

- Department Medical Director

- Peer Support and Critical Incident Stress Team Representatives

- Budget Director

- Friends of the Dallas Fire-Rescue Department (private supporters of the department including philanthropists who assist families of fallen firefighters)

This group of more than twenty people met for more than eight months to discuss, evaluate, and begin building a behavioral health program that could benefit all members of the DFR family (uniformed and civilian).

Initially, the group focused on changes we could immediately put in place to decrease the likelihood of a member who was facing disciplinary action from engaging in self-harm, either through additional reckless behavior or by suicide. The group also discussed how to break down walls between administration and operations personnel and what role the different groups (those in the meeting) could play in this process.

Traditionally, when a DFR member was initially charged with certain offenses (criminal activity or arrest, positive drug or alcohol test, or other serious offense) they were placed on administrative leave, removed from duty and sent home that day. It was decided that in the future members would be allowed to remain at their work site so they could initiate immediate contact with one of the department’s chaplains, peer counselors or firefighter association representative.

The firefighter would not be responding to emergency calls, but would also not be required to go home alone. Those that wanted to go home would only be allowed to do this if they could be released to a family member who could be with them and support them. While this might seem very reactive to the recent suicide, everyone in the group was supportive of implementing the new process, and over a year later we have followed this model with success and positive feedback from all personnel.

The next step was determining what support services were available to members of the department. We knew that a number of members were already engaged in various counseling programs, some related to Post-Traumatic Stress Injury (PTSI), others related to substance use disorders or other psychological or personal issues. Some of these services were paid for by the City’s Worker’s Compensation Program, some through health insurance, while others were paid for out-of-pocket by the members. Feedback we received from our field personnel about the city’s Employee Assistance Program (EAP) was less than favorable.

We then drew out on a white board what began looking like a funnel but ended up looking more like an hourglass. At the top were our current issues: Member PTSD/I, suicide, and substance use; limited direction from department command staff; and seemingly disconnected programs. The narrow part of the initial funnel was the “choke point” wherein the department lacked the ability to consistently and reliably identify members who needed assistance, but also lacked the ability to consistently and reliably provide assistance to them. At the bottom of the funnel, which became the base of the hourglass, sat the myriad of programs the department envisioned to develop to assist members.

Below is a visual outline of what the Gap Analysis Working Group accomplished. The outline begins with the intake funnel, followed by a step-by-step overview of the different challenges and accomplishments of the working group. Once the gaps were identified, the team transitioned to what programs could be put in place to address those gaps. We implemented a number of temporary “stopgap” solutions, primarily revolving around programs that were already in place within our organization or the City of Dallas (Fire Department Chaplains, peer counseling, Critical Incident Stress Management, Employee Assistance Program, Police Department psychologists), with the intent of expanding several programs in addition to the development of new programs. The diagram below details the Working Group processes.

Six months into the process, we had met with representatives from the University of Texas at Dallas to discuss mindfulness training, as well as a psychologist who conducts resiliency training for Los Angeles County Fire Department and Sheriff’s Department. We hosted a number of different mental health institute groups who provided us with overviews of behavioral health programs they provide for military veterans as well as a few that have worked with first-responders.

The local firefighters’ association was successful in securing donated bed space for DFR members at several behavioral health centers across the Dallas metropolitan area. This equated to 180 days/nights per year of free bed space (room and board) at these facilities. The only charges were associated with the care provided by any psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, or therapists. They agreed that the amount billed would not exceed what the employee’s insurance considered “reasonable and necessary."

Additionally, the International Association of Firefighters has a new behavioral health center in Maryland, providing up to 90 days of in-residence treatment for various issues related to PTSI, depression, and substance use disorders. Lastly, we began working with local treatment and recovery centers to develop first-responder-specific 12-step programs.

Next, the work group began to develop ways to connect department members to 24-hour assistance. This was accomplished through multiple pathways. First, we subscribed to an existing website created by the Phoenix-Area Firefighters Association. FireStrong.org allows individual departments to customize portions of the site, but also provides generic guidance to departments that are unable to pay the required site hosting fee.

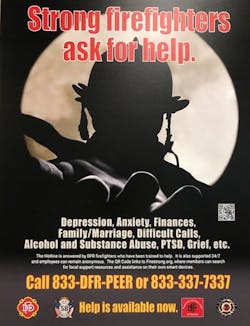

DFR acquired two sites—one managed by the department, the other managed by one of the firefighters’ associations. The two sites are nearly identical, with the only exception being the various products that only the association can offer, i.e., IAFF Behavioral Health Center. The website can be accessed through a typical web address or through a QR code, thus assuring anonymity of the individual seeking assistance through this pathway. A poster (image below) was developed containing the information about the website, along with a 24-hour contact number for DFR peer counselors.

DFR’s four peer counselors carry a phone with them 24 hours a day. The number listed rings all four phones simultaneously and stops ringing once any one of the four phones is answered by a trained peer counselor. All information regarding assistance unique to Dallas can be provided by a peer counselor, chaplain, or via the website. Again, all conversations with peer counselors are confidential and a member does not even need to disclose who they are and may remain anonymous. The posters were placed at every DFR work location in the city. The multiple routes of access/intake were designed to allow personnel from different generations to utilize the method that is most comfortable and familiar to them.

In addition, DFR’s Medical Director began leading an effort to support Department members and other first responders from the Dallas Police Department who are identified as having impairment due to behavioral health issues and/or substance use disorders. The RENEW (Recovery Employee Network and Emotional Wellness) Program seeks to develop a medically-managed process to support, advocate for, and if need be monitor Dallas first responders who have alcoholism, drug addiction or other significant behavioral health issues so that they may be safely and appropriately returned to duty, potentially saving both lives and careers. A steering committee has been formed and has met during the past year to develop a vision and action plan in order to begin implementing various aspects of this innovative program.

Finally, we recognized the need to support a cultural shift within the department, effectively creating a climate where it was not only OK for an employee to ask for help, but where asking for help was encouraged and seen as a sign of strength. We recognize that this cultural shift will likely take years to realize.

To begin, DFR has begun providing resiliency training for our new recruits. The recruits are introduced to the challenges of the profession and the possibility of developing PTSD/I . This training is provided by a DFR member who has personally struggled with PTSD for several years. This initial training is conducted within the first month of the new recruit arriving at the fire academy.

The second piece of the training was provided about one month before the new recruits graduated from the six-month fire academy. In a second class, a partner of a DFR paramedic who was shot in the line of duty discusses the challenges of that event and the struggles he and his partner have had dealing with the emotional toll from that day. The training is completed just before graduation, when members of the peer counseling team, CIST group, and chaplains meet with the new recruits and their family members to talk about the challenges of the job and the resources that are available to assist them should they need help.

Information has also been distributed to field personnel and company officers regarding the new programs, encouraging them to ask for help when they believe a colleague needs assistance. The peer counselors, CIST group, and chaplains have also been making the rounds throughout the stations talking to members about the programs that are now available.

Although the work is far from completed, we believe that good progress has been made and that the members of the department have been both receptive and supportive of the programs. However, we believe that much of the receptiveness is due to the focus on these issues since the firefighter’s death.

It will be critical to maintain that focus and awareness as time goes on in order to avoid complacency. Day-to-day oversight of the program has now transitioned from being led by the Fire Chief to being led by the Deputy Chief over DFR’s Safety Division. Meetings have also transitioned from the original schedule of every two weeks to once per month. As a working group, our intent is to monitor the existing programs with the goal of continuously improving available resources through feedback and observation.

Next Steps: The Wellness Pyramid and Member Assistance Pathway

DFR’s efforts have also been introduced to a broader state audience. As Chair of the Governor’s First Responder Advisory Council, Chief David Coatney is tasked with bringing forward new and innovative ideas to assist in first responder safety. He presented an overview of DFR’s program to the First Responder Advisory Council and suggested that we consider drafting a position-paper on managing behavioral health issues among first responders across the State of Texas. The proposal has been moved forward and a small group met to discuss the overall model and bring back a recommendation to the council.

Chief Coatney and Dr. Marshal Isaacs from the Dallas Fire-Rescue Department, Eric Epley, Executive Director of the Southwest Texas Regional Advisory Council on Trauma and his staff, along with Dr. Chetan Kharod, Colonel USAF, Special Operations Medical Director, met to outline the program DFR had begun to implement and added additional areas for consideration in creating a mind-map to present to the group. Below is an image drawn on a Smart Board during the meeting:

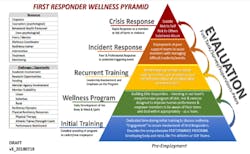

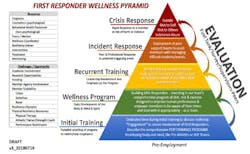

As you can discern from the drawing, multiple areas were being considered to address education, training, treatment options and intervention strategies. The drawing was refined to become the First Responder Wellness Pyramid as pictured below:

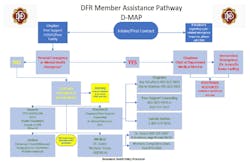

The First Responder Wellness Pyramid represents our initial thoughts on the vision that the Dallas Fire-Rescue Department is working toward that we believe provides a holistic approach to improving both mind and body resiliency. In addition, DFR developed a graphic of a pathway to assist company officers to better understand the actual process that can be used when a member needs assistance. The Dallas Fire-Rescue Member Assistance Pathway (D-MAP) is a guide that an individual, fire company officer, or anyone else involved in the process can follow to obtain appropriate assistance when needed.

Challenges and Our Hope for the Future

In most organizations, there will be challenges to implementing new programs. One of the main challenges related to implementing a behavioral/mental health program relates to stigma—the perception by some members of the organization that a person who self-reports or asks for help is weak, sick or somehow "less than." There is concern that this may cause other personnel to question the stability of the person who has self-reported or sought help.

We know that in the past this has led to personnel being shunned, reassigned, or sometimes even losing their jobs. Similarly, if an organization identifies an individual as needing an evaluation or treatment, especially if they are compelled to undergo a fit-for-duty psychological assessment, apprehensions may surface among colleagues, peers, subordinates or supervising officers.

Today, laws such as the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) are in place to protect people with a variety of behavioral and physical health issues. While these protections include the first responder community, awareness and adoption of progressive policies related to the law may be lagging compared to that of other industries.

More importantly, simply having laws in place does not automatically afford protection nor does it change the working environment, the stresses of the job, the organizational culture or the opinion of or response to members of the affected by behavioral health issues. Education is one of the most effective ways to change both opinion and culture, and it helps move organizations forward. Creating an environment where it is considered acceptable and appropriate to not only admit you are having difficulty with a particular issue, (such as a particularly horrific response or the compounding of multiple responses or issues) helps not only the individual, but can also help propel a cultural shift within the organization. This can ultimately serve to decrease if not remove the stigma often associated with behavioral health issues.

We still see challenges related to members’ willingness to use certain services. To address concerns with our Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), the provider has created a pathway specific to emergency responders and works with the GAP Workgroup to improve the understanding of challenges specific to first responders. Critical Incident Stress Management/Debriefing teams (CISM/CISD) may actually cause harm while trying to do good when not performed by properly trained individuals and according to best practice standards. Dallas CIST members have all been trained by a leading CISM instructor and utilize a volunteer Mental Health Clinical Director to ensure that interventions are performed appropriately. Programs such as mindfulness and resiliency training are unfamiliar to most first responders who by and large are naturally resistant to new programs. Introducing these concepts in the academy is intended to make them part of the culture of the department.

Finally, there is little evidence on which to base decisions on how to expend scarce behavioral health dollars and what the long-term value of such programs might be. Each of these challenges will need to be explored in order to determine the next best steps in developing a comprehensive behavioral health program for our department as well as other first responder agencies. It is our hope that this article will serve as a springboard for discussion about how best to serve and advocate for those that serve and advocate for others.

The bottom line is simple: Our members are our brothers and our sisters, our colleagues and our friends. We have invested time, money, energy, education, training, care and, dare we say, love, in one another. We should not throw anyone away because they face a behavioral health challenge and we must do everything in our power to avoid another death in our family due to suicide.

In loving memory of Dallas Firefighter Paramedic Taj Wright.

Further Reading/References:

SAMHSA: First Responders: Behavioral Health Concerns, Emergency Response and Trauma, May 2018

Report on Mental Health Access for First Responders. 85th Texas Legislature, December 2018

JEMS: Survey Reveals Alarming Rates of EMS Provider Stress and Thoughts of Suicide, September 2015

Cumulative PTSD Among First Responders, Ben Pierce, Pulaski County Sheriff’s Office, April 2018

About the Author

David Coatney

David Coatney has over 37 years of experience in public safety and currently serves as the Agency Director/CEO of the Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service (TEEX). Coatney’s fire service career began with the San Antoino Fire Department, where he served for over 25 years, retiring as an assistant fire chief.

Coatney continued his career in the fire service by serving as the fire chief for the Round Rock Fire Department, then accepted the position as the fire chief for the Dallas Fire-Rescue Department.

His experience includes serving as a firefighter, paramedic, fire company officer, department safety officer, special operations chief, operations chief, and emergency management coordinator.

He holds a Master of Arts Degree in Organizational Management, is a Certified Emergency Manager, Chief Fire Officer, Executive Fire Officer, and a graduate of the Naval Postgraduate School’s Executive Leaders Program in Homeland Security.

In addition to his full-time role, Coatney also serves as the Chair of the Texas Governor’s First Responder Advisory Council, a member of the FEMA Region 6 Regional Advisory Council, and as a committee member on the Texas Division of Emergency Management Advisory Committee.

Dominique Artis

Dominique Artis became Chief of the Dallas Fire-Rescue Department on December 28, 2018. He has 24 years of experience in public safety and has served in a variety of positions during his career. Prior to his appointment, he was the Assistant Chief of the Administration Bureau overseeing Training, Maintenance, Clothing and Supply, Recruiting, Chaplain Services, and the Environmental Management System for the department. Chief Artis also served as Captain, in both Emergency Operations and the Emergency Medical Service Bureau, a district swing Lieutenant, Driver Engineer, and Fire Rescue Paramedic. Dominique holds various certifications including Master Firefighter, Master ARFF, Fire Officer I, Fire Instructor I, and USAR Task Force leader.

Chief Artis is a devoted husband of 19 years and a supportive father to two daughters. He grew up in Dallas, Texas, and graduated from Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School. Afterward, he went on to attain a bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering and Technology from Prairie View A&M University, as well as graduate from the National Fire Academy and the Executive Fire Officer Program. Chief Artis currently serves on various committees at the regional and state level.

Eric Epley

Eric Epley is the Executive Director of the Southwest Texas Regional Advisory Council for Trauma (STRAC) in San Antonio, TX. STRAC serves 22 counties that stretch over 26,000 square miles, whose membership includes 55 hospitals, 75 EMS agencies and 14 helicopter bases.

Epley is a Certified Emergency Manager with nearly 35 years in public safety response and administration, a nationally registered paramedic for over 30 years and a licensed police officer for 13 years, serving as a tactical paramedic at the Branch Davidian standoff, the Republic of Texas standoff and other high-profile Texas incidents.

Cristian Hinojosa

Cristian Hinojosa has served the Dallas community as a public servant for nearly 20 years. He currently serves as a Deputy Chief, overseeing departmental operations for half the city. He holds a Master Degree in Public Administration and is a nationally featured speaker and author on a multitude of topics related to the fire service. Prior to joining the Dallas Fire Department, Cristian worked as an investment banker in New York City and Dallas.

During his career, Cristian has led the second largest DFD employee association, representing over 500 firefighters. This role carried substantial political and administrative responsibilities and included extensive interaction with DFD Command Staff, City Council, and the City Manager on a regular basis. More recently, he helped found and lead the DFD Peer Support Program, providing outreach and support to firefighters. He is passionate about his calling and considers it one of his life's greatest honors to wear the DFD uniform!

Cristian can be readily reached at: https://www.linkedin.com/in/cristianhinojosa

Lauren Johnson

Lauren Johnson is an Executive Fire Officer and has worked for Dallas Fire-Rescue for the past 20 years. She is currently the Deputy Chief over Safety & Performance.

Tami Kayea

Firefighter/Paramedic

Tami Kayea has been a firefighter and paramedic with Dallas Fire-Rescue Department for 22 years. She has risen through the ranks and is currently a deputy chief. Kayea holds a master’s degree in management and leadership and is a graduate of the Executive Fire Officer Program through the National Fire Academy.

Elaine Maddox

Chaplain Elaine Maddox has been involved in caring for the firefighters, retirees and their families with Dallas Fire-Rescue since 1981. She first got involved with the fire department after two firefighters died in the line of duty on Aug. 21, 1981.

Chaplain Maddox has been a uniformed member of Dallas Fire-Rescue since 2007. In 2010, she accepted the calling as Chaplain. As Chaplain she offers care, comfort, and guidance to the over 2,000 members of the department.

Chaplain Maddox has received numerous awards throughout her career both from Dallas Fire-Rescue and State and International Organizations.

Ray Schufford

Ray Schufford serves as a Chaplain for Dallas Fire-Rescue. From hospital visits to officiating weddings to onsite fire detail and crisis management, Ray supports the 2,000 members of the fire department, along with its retirees. He provides guidance, encouragement and counseling as a trusted comrade. Ray is a 25-year veteran firefighter/paramedic for Dallas Fire-Rescue and was promoted to the Chaplain position in February 2017.

S. Marshal Isaacs

Dr. Marshal Isaacs has served as the Medical Director for the Dallas Fire-Rescue Department since 2006. In 2015, he was appointed Medical Director for the 13-city consortium of fire department-based EMS programs known as the UTSW/Parkland BioTel EMS System.

Dr. Isaacs also serves as a senior Attending Physician and Faculty Member in the Department of Emergency Medicine (EM) at the Parkland Memorial Hospital Emergency-Trauma Center and is a full Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School.

Dr. Isaacs has a special interest in addiction recovery and serves as the Chairman of the Parkland Committee on Practitioner Peer Review and Assistance as Co-Chair of the Dallas County Medical Society’s Physician Wellness Committee. Dr. Isaacs is a tireless advocate for physicians, nurses, firefighters, paramedics and police officers suffering from impairment due to substance use disorders.