Health & Wellness: Firefighter Suicide and the Link to Burnout and Lack of Meaning

Long shrouded in mystery, firefighter suicide recently emerged as one of the foremost problems in the fire service. Although researchers still build consensus through various studies, firefighters die by suicide at a rate that’s significantly more than the general population. Additionally, some estimates of rates of suicidal ideation for firefighters range as high as eight times that of the general population. These numbers tell us that it’s imperative that we engage with mental health in the fire service.

Burnout and meaning

Recent research confirmed for the fire service and mental health professionals several factors that influence firefighter suicide, including the effects of post-traumatic stress, sleep problems and substance abuse. The potential effect of post-traumatic stress in regard to suicide was recognized for years for police, military veterans, ambulance crews and disaster workers, as are other factors, such as burnout and meaning in life. Burnout for those who work in jobs that help others is defined as the experience of emotional exhaustion, loss of empathy and loss of a sense of personal achievement. Burnout is well known to be linked to depression and suicide in nurses and doctors. Although burnout is not well studied in firefighters, some research from Poland shows that it’s a significant factor in Polish firefighters’ mental health problems.

The idea of meaning in life, often also called purpose, was made famous by the psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl. Meaning can be thought of as the “why” to engage in a task or endure suffering. Researcher Evan Kleiman defines meaning as a sense of purpose that’s believed to matter in a way beyond the individual living that life. Although meaning is by its nature subjective, research shows that its presence can serve as a strong protective factor against suicide. Particularly, the protectiveness of meaning often becomes stronger as depression and other mental health issues grow more severe.

In a 2022 study that involved 253 firefighters from several departments in the metropolitan area of a large West Coast city, the significance of burnout, workload and meaning in firefighters was explored. Specifically, the study measured participant responses to measures of suicidality, burnout, meaning, call volume, secondary traumatic stress and relational belongingness.

Suicidality

Suicidality is an umbrella term that includes suicidal ideation and past suicide attempts. The 2022 study measured suicidality via a questionnaire that was designed to measure risk for suicide. The basic question that guided the study: How significant are burnout and lack of meaning for influencing firefighter suicidality? The study also compared the influence of meaning and burnout versus trauma exposure on suicide risk.

The resulting statistical analysis showed several important trends that might be useful to better understand how to combat firefighter suicide. Most troubling, 27 percent of the participants were classified as at high risk for suicide. This result echoes other research that points to elevated suicidal behaviors among firefighters.

Also troubling, 33 percent of the participants reported that they contemplated suicide sometime in the previous year. This rate starkly contrasts with the estimated rate of 14.3 percent for lifetime suicidal ideation in the general population. Additionally, suicidality scores were linked more strongly to burnout and meaning than they were to secondary traumatic stress. Although trauma is real, it had less influence on suicidal ideation or past attempts of those who responded to the survey than either burnout or lack of meaning had.

Finally, experiencing problems with significant relationships, either personal or professional (technically, “thwarted belongingness”), was the strongest influence on suicidality scores, nearly twice that of trauma exposure. This last finding also supports what already is known: Strong crew bonds and supportive off-duty relationships are the foundation of firefighter mental health.

One additional result might be the most important result of the study. Burnout and meaning become particularly important as suicide risk rises. For the group of firefighters who ranked as low risk, suicidality was linked only to thwarted belongingness and traumatic stress. Conversely, for firefighters who are at high risk for suicide, both burnout and lack of meaning showed strong links to suicidal behaviors, and the effect of each is stronger than the effect of traumatic stress. Again, the effect of trauma is real, but for many of us, it likely isn’t the most damaging part of the job.

Call volume

These results make intuitive sense. Burnout and lack of meaning are becoming significant in the fire service at the same time that workload is increasing steadily and that the nature of the job is changing. For example, from 1974 to 2019, my department saw the rate of structural fires fall by half. Over the same period, overall call volume rose by more than 700 percent. Further, much of that increase was for low-acuity medical calls and nuisance fires.

So, what does this information tell us? At a minimum, the possibility that, on average, firefighter suicide is being influenced more by burnout and meaning than trauma indicates that our conversation around mental health should include these topics. For years, the effort to address mental health, from research to employee assistance programs, has focused on trauma and substance abuse. That’s good. However, the results of this study, along with a small handful of others, tell us that we should add an exploration of how to address burnout and meaning into our mental health effort. Additionally, this information indicates that we should continue to conduct research to verify, correct and expand on the results of studies, such as the 2022 work.

What to do?

Addressing burnout and lack of meaning is different than addressing trauma. Although there are many mental health resources that focus—and appropriately so—on treating post-traumatic stress for individuals, burnout is both an individual and a system issue. According to Christina Maslach, who is a pioneer of research on job burnout, burnout arises from chronic excessive stress in a work environment. Organizational approaches to mitigating burnout include reducing workload and adjusting work environments to ensure that they are a good fit for employees. Individual approaches to addressing burnout include adjusting ideals and expectations about the job, reducing emotional investment and taking time off when needed.

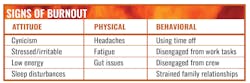

In the short term, a good approach to burnout is to help each other. Burnout often is more apparent to others than to the individual who is experiencing it. As fellow crew members and company officers, we can help to recognize the signs of burnout in others.

Unlike burnout, meaning is much more subjective and specific to each individual. When meaning is present, people can believe that they can surmount any challenge to accomplish their purpose. When it’s absent, we lose momentum and drive.

For many of us, this job promised a sense of purpose, including helping people; the challenge of high-stakes, dynamic emergency scenes; the physicality of structural firefighting; and working as part of a team. What once was meaningful early on might be less so now.

Additionally, for many of us, the job itself changed over the years. Meaning is something we pursue and discover as we move through life. We never grasp it with finality. If you lack energy for the job, it might be time to focus on a different aspect of it that aligns with your “why.”

Matt Coffey

Matt Coffey is a 19-year member of Portland, OR, Fire and Rescue. He currently serves as a company officer. Coffey holds a Master of Science in mental health counseling and specializes in working with first responders. He also conducts research into the effects of burnout and meaningfulness on firefighter mental health.