FL County's 9-1-1 Operations in Crisis

It was supposed to be a day full of hope for what the New Year would bring, but it began with a cry for help so guttural it carried throughout the Deerfield Beach house. Keishawn Johnson Jr., not even 3 months old, was turning blue. His mother, full of terror, screamed: “My baby! My baby!”

Cory McNeil, one of many adults staying at the house that included a bed full of sleeping children, grabbed a phone and frantically pounded the numbers 9-1-1. The phone rang and rang and rang — and rang some more — as Darrol “Molly” Glasco continued to scream for someone to help her baby boy.

“Everyone was like, ‘Oh no, no, oh no! Call the ambulance. Call the police,’” McNeil said.

Someone else grabbed a phone. So did a third person. At least three callers dialed 911 and no one answered. One person hung up and tried again. And again. So did others.

Beginning at noon on Jan. 1 and for the next eight or so minutes, no emergency responder spoke to any of the frantic callers.

Records from Broward’s regional 911 communication center, and interviews with 911 callers and current and former county employees, paint a terrifying picture of an emergency response system that is leaving callers in danger. And now a family says their baby is dead because the people responsible for sending emergency workers to life-or-death situations didn’t even answer the phone.

In a months-long investigation, the South Florida Sun Sentinel discovered thousands of unanswered 911 calls and talked to desperate callers who never connected with the help they needed. As alarm about the public safety crisis spreads, fire chiefs and city officials are scrambling. But nothing’s been done — and the 911 call centers remain dangerously understaffed.

Sources privy to how the 911 system operates describe a job where call-takers work 16-hour shifts, not the scheduled 12 hours. And the stresses of being short-staffed are too much for many. Sources say most new hires don’t stick around long, and there have even been times when a worker walked off the job during a lunch break.

When no one picked up the 911 calls about the unresponsive baby on Jan. 1, and it was apparent no ambulance with life-saving paramedics would come racing down the street, a desperate Keishawn Johnson Sr. jumped into a friend’s car, leaning over his son, blowing air into the baby’s lungs during the 4-mile trip to Broward Health North.

Had someone picked up one of the 911 calls from the car full of people, the communications operator could have told the 23-year-old father to also do chest compressions — something imperative when doing CPR. Johnson had no idea he was doing CPR wrong, and on the way to the hospital he kept thinking to himself, “This can’t be real. This can’t be real.”

A dire picture of a county in crisis

Johnson is far from alone. And this public safety crisis is no secret to the Broward Sheriff’s Office, which operates three regional 911 call centers for the county.

The emergency 911 phone system logs all the calls, even when the caller hangs up the phone before connecting. The county’s own data paints a dire picture.

Last year, 166,755 callers hung up before connecting with a call-taker. The number of abandoned calls — which includes accidental misdials — has steadily increased over the past three years, the data shows. Abandoned calls increased 26% from 2019 to 2021, the South Florida Sun Sentinel found.

The activity in February, the most recent report available, provides a look into the phone-ringing chaos of the 911 system in Broward.

That month, there were 14,505 abandoned calls, according to the county’s reports. That doesn’t compare favorably to past Februarys — the grim trend has only gotten worse.

According to the county, emergency call-takers should answer the phone within 10 seconds at least 90% of the time during the busiest hour of the day. The Sheriff’s Office’s 10-second goal is based on a longtime national standard, which was loosened in 2020 to 15 seconds.

The call center failed to meet the 10-second goal on 13 of the 28 days in February, the records show.

Still, February was the first time since September that the county hit that benchmark for at least half of the month. The county met its target on just five days in December.

For example, on Feb. 6, 230 calls came in between 5 and 6 p.m., the busiest hour for emergency calls that day. Just 80 — about one in three — were handled within the 10-second benchmark.

Data shows that the quality of service for 911 rapidly deteriorated at the end of 2021 and that problems persisted into the new year. The problem hit its zenith in December 2021, when nearly 30,500 calls were never connected to an operator.

A Broward Sheriff’s Office spokeswoman downplayed the problems, but acknowledged staffing shortages, problems with retention, and the impact that COVID surges had on their operations.

“The COVD-19 pandemic has certainly had negative effects on public safety institutions, with PSAPs [911 centers] clearly not immune to unexpected, dramatic and impactful staffing losses,” said Veda Coleman-Wright, a spokeswoman for the Broward Sheriff’s Office. “However, despite these obstacles, the regional system does provide call answer times that routinely meet industry best practices.”

The agency released statistics this week to the Sun Sentinel highlighting an average phone pickup of one minute or less on most calls. Those figures ignore the thousands of times a person in an emergency never reached a call-taker at all.

Coleman-Wright acknowledged how terrifying that must be to somebody in a crisis.

“As seconds tick by, it can seem like an eternity to someone experiencing one of the worst moments of their life,” Coleman-Wright said. “The dedicated members who work in our Department of Regional Communications understand this, and that’s why 911 operators and dispatchers work with the utmost care, speed and diligence in answering the [phones].”

Records show Keishawn and his father arriving at the hospital 13 minutes after the first call to 911 was not answered. Life-saving measures — intravenous drugs, a defibrillator to restart the baby’s heart, tubes to open his windpipe — were too late, records show. At 12:33 p.m., a half-hour after the flood of 911 calls started, Keishawn Donnel Johnson Jr. was pronounced dead. The 12-pound baby was 12 days shy of turning 3 months old.

“Your son didn’t make it,” a hospital doctor told Johnson. Johnson said his world began to spin and he begged doctors to take his own heart and give it to his son.

“They are supposed to be there to provide support — to serve and protect us that day. But there was no one to serve or protect. My son didn’t get served or protected,” Johnson said. He said a sheriff’s deputy asked him why he didn’t call 911 so paramedics could help his child on the way to the hospital and get him there quicker. The question stung.

“I still can’t believe it happened. [The detectives] looked at me and were like ‘Are you sure no one answered?’ I believe my son would still be here today if they answered. But the fact is, nobody answered.”

‘This never should have happened. We need more people’

Some 2.2 million calls come into the regional call center a year. About half of them are non-emergency calls. The Broward Sheriff’s Office Regional Communications center is responsible for taking 911 and non-emergency calls for all municipalities in Broward except Coral Springs and Plantation, which never joined the regional system.

Other municipalities could break away as frustration mounts with unanswered calls, the Sun Sentinel has learned.

The regional 911 communication system has been short-handed for the last few years, according to Coleman-Wright. The start of the pandemic two years ago exacerbated the staffing problems, sources say. Currently 297 people are responsible for staffing the phones and fire and police radios around the clock, seven days a week, at the three centers. As of Wednesday, 69 vacancies existed for communications’ operators, the Sheriff’s Office said.

Many current and former employees shared their concerns only on condition of anonymity for fear of jeopardizing their careers.

Those sources say even the agency’s staffing goals, if they were met, would be far too low. They say the region’s three centers are operating in crisis mode — many days with operators asking callers if they can be put on hold.

When calls pile up because there aren’t enough communications operators to answer them, a deep, jarring bonking sound echoes around the centers. When calls are dropped, a different sound notifies the workers. The constant clatter, sources say, along with stressors of dealing with people suffering a crisis and the lack of manpower can be too much at times.

And now, with word spreading through the centers that a baby died, the internal crisis is all the more palpable.

“This never should have happened,” a source said. “We need more people to alleviate the stress of all this. We would have been able to help [Johnson] administer CPR correctly. It’s horrible. It’s really horrible.”

Another source said what happened to the baby was exactly what many feared would happen one day. “This job is killing us little by little. It’s like they drained the blood from [us].”

Regional communications operators normally are scheduled to work three 12-hour shifts in a row and a six-hour shift on Wednesdays. Sources say there are times when so few operators are working that supervisors make urgent pleas for workers to come in earlier, stay later or give up their days off.

The shortage of 911 communications workers is not unique to Broward County.

Various media reports reveal a shortage from coast to coast.

The Denver Gazette reported in late March that the number of people taking calls was at 60% of normal.

Philadelphia in February said it should have 350 people employed at its 911 center. It had 278. In late February, a television station reported that four people quit working at a Los Angeles 911 center in a single day and that 24,000 callers waited two or more minutes for someone to answer the phone.

“Staffing for Public Safety Answering Points [911 call centers] traditionally finds itself in an unyielding rotation of new hires and departures, with attrition rates climbing well above the 20% found during normal operations. The COVID-19 pandemic only aggravated this issue,” BSO spokeswoman Coleman-Wright said.

The Broward Sheriff’s Office said it is making a constant effort to recruit new staff. In March, for example, the agency shared on all of its social media accounts a plea for applicants. “BSO is putting out its own call for help — asking for qualified, dedicated people to become 911 operators. If you or someone you know is interested in becoming a 911 call taker, please visit http://jobs.sheriff.org,” the agency wrote on Twitter.

‘How hard is it ... to answer a damn phone?’

The kitchen walls to Judith Garwood’s Hollywood bungalow are still standing — for now — but most everything inside melted after an early-morning fire on April 10.

Garwood, 75, said she woke up in the middle of the night to flames about thigh-high in her bedroom. She grabbed a phone and called 911. When no one answered she grabbed a fire extinguisher. Garwood had no idea what to pull and what to push. So she called 911 again. So did multiple others.

As Garwood and her boyfriend fled the house, a 23-year-old man who lives across the street raced through the cluster of closely packed-in homes, banging on doors to warn people the fire at the neighbors’ home could spread. He pulled out his phone to call for help. So did others.

Martin Lisi had been sound asleep when his daughter woke him up to say there was a fire across the street. He opened the door to see thick plumes of black smoke. He too called 911 but said the call got disconnected. This happened repeatedly, he said. Soon there was an inferno.

The 23-year-old said when he heard at least four people scream that no one was picking up the 911 calls, he raced back across the street, jumped in a car and drove to a Hollywood Fire Rescue station a few blocks away.

He got there just as another frantic person drove up. One ran to the main door, another to the firehouse’s large bay doors. Both pounded, screaming, “Help! Fire!”

A firefighter woke up and opened the door. The 23-year-old said the firefighter seemed surprised to learn there was a fire nearby, telling the two men the station had not received any radio calls from fire dispatch workers.

“This isn’t a camp fire. The entire house is engulfed,” the 23-year-old told him. As they stood there explaining what was going on, the communications radio started blaring, records show.

At 1:45 a.m., about 15 minutes after the first 911 calls, firefighters arrived at the house, but it was fully engulfed. Flames licked at a utility pole and a mango tree.

Considering how close the fire station is to Garwood’s home, she thinks she would not have lost everything if someone had picked up the phone. Hollywood city officials agree.

George Keller, deputy city manager for public safety, and Jaime Hernandez, emergency and governmental affairs manager, said that Hollywood Fire Rescue assessed the fire damage and indicated it could have been limited to a single room where the blaze started had units been dispatched sooner.

“Hollywood Police and Fire units have reported for years about dispatchers inability to provide satisfactory assistance on calls for service. … Hollywood residents continue to complain about delays when calling 911. The issue has become intolerable and dangerous,” the men said in the letter to Tracy Jackson, director of the county’s Office of Regional Communications and Technology. Broward County is ultimately responsible for the 911 system, but it’s operated under a contract with the Sheriff’s Office.

Fire Chief Dan Booker also sent Jackson a letter: “I wish I could say this is an isolated incident but we have seen an increase in delayed calls, miscoded calls and unanswered radios. … I encourage you to work with the Broward Sheriff’s Office to develop a plan to address these concerns.”

Garwood is angry. She said she was given $500 from the Red Cross but has no idea how she can rebuild her whole life on that.

“How hard is it to hire somebody to answer a damn phone? If it’s staff shortages, then I don’t care if you have to hire your grandmother to answer the damn phone,” Garwood said.

Cities frustrated: ‘We’re here to protect our citizens’

The county and the Broward Sheriff’s Office formed the regional dispatch system for 911 in the fall of 2014, bringing in nearly all Broward municipalities. But less than eight years in, municipal leaders say the situation is grim and are looking for resolutions or pulling out altogether.

Coconut Creek police and fire rescue are leaving the regional system in October and moving to Coral Springs’ 911 dispatch system. Pompano Beach is weighing its options, said Fire Chief Chad Brocato.

Fort Lauderdale city commissioners Tuesday asked for a staff report on what it would take to create their own 911 system, something considered years ago but not pursued because the city manager at the time said the costs — in the millions — would be too much and not justified.

The report was requested after two residents, including a retired out-of-state fire chief, complained at the commission meeting that details they provided in 911 calls about a motorcycle crash that left a person with a partial leg amputation were not relayed properly from 911 to responding emergency workers.

“We’re going to revisit the issue,” Mayor Dean Trantalis said. “It does merit a further review if the county system is still falling short. We’re here to protect our citizens. At what price is a life when we have the opportunity to save one?”

Fort Lauderdale Fire Chief Rhoda Mae Kerr told commissioners that they frequently hear about calls to 911 not being picked up. She said the Sheriff’s Office responds that it is about 90 people short. “That’s not OK,” Kerr said.

Coconut Creek Mayor Josh Rydell said the city had fielded “dozens of resident complaints saying we’re calling 911 and nobody answers” and had encountered issues with dispatchers not knowing the geography of the cities. ”It’s wasting valuable time asking where somebody is,” he said. “You can’t put a value on life.”

At an April meeting of Broward’s fire chiefs, a decision was made for the fire chiefs to join with the police chiefs to form a task force to address concerns about the regional system and to work toward finding resolutions, said Stephen Gollan, a battalion chief for Fort Lauderdale Fire and Rescue who was recently named the spokesman for the Broward fire chiefs’ group.

“[We] are aware of the ongoing situation with delays in answering calls to the 911 system in Broward County,” Gollan said.

The Sheriff’s Office and Broward County created the regional system with promises for better and quicker services. But from the onset, the bigger system was besieged by troubles, as detailed in a 2016 series of articles in the South Florida Sun Sentinel about 911 call-takers’ mistakes; calls to 911 that went unanswered, and a four-hour malfunction due to a mix of human and technical error during a software upgrade. There was also an incident in 2015 with a dispatcher ordering pizza and leaving phones unanswered for eight minutes. The system’s troubles also hampered the response to the Parkland school shooting in February 2018.

With the current issues, Broward County has put the onus on the Sheriff’s Office, saying “every 911 call deserves a prompt and appropriate response.”

“Broward County will continue to provide the infrastructure to ensure that the system is fully operational when our citizens need it most,” said Jackson, the county’s emergency services director. “We will also continue to work with the operator [The Sheriff’s Office] as they fulfill their responsibility to address any potential issues that might impact performance.”

‘One of the most traumatic events of my life’

Hillary Borris noticed her dad was up later than usual watching TV one night in February at their Coconut Creek home. So she asked him a question. He didn’t respond. She moved closer, seeing that his eyes were open. His body was stiff. He was unresponsive.

“He was staring at me without actually seeing anything and was unable to communicate,” she said.

Call after call to 911 went unanswered. Then Borris’ mother started calling. Then her brother.

Screenshots from Borris’ cellphone show she made five calls in a desperate attempt for help. The first call to 911 at 12:16 a.m. rang for almost a minute, but there was no response, so she hung up. She called again at 12:17 a.m. when it rang for a full minute, and again at 12:19 a.m. and 12:20 a.m. A second screenshot shows she tried again at 12:21 a.m. All told, Borris spent 2 minutes and 48 seconds trying to get someone to answer, she said.

Police records reflect slightly different numbers: The first call from her cell came in after midnight and rang for more than a minute. Only a second call followed that lasted just a few seconds longer than the first.

But both Borris and city documents reflect that her mother called twice, with the first call lasting 1 minute and 54 seconds. Her brother called three times, according to the records, with the first call lasting more than a minute and the second call lasting more than two minutes.

“I’m panicking. We’re panicking,” Borris said.

The ambulance arrived 15 minutes and 34 seconds after the first call to 911, according to records obtained from the Coconut Creek Police Department.

The Borrises were not the only ones trying to get through to 911 in the early overnight hours of Feb. 15. Angela Mize, the director of the Sheriff’s Office’s Regional Communication Divisions, said the number of calls to 911 from midnight to 1 a.m. was extensive and surpassed historic predications by 74% — 190 calls.

It’s an awful feeling when no one answers, Borris said.

“There is no world in which anyone should have to go through this during an emergency when time is of the utmost importance,” she said. “... I can only say it feels like an eternity when you believe your loved one is moments away from the end.”

Joseph Borris, a diabetic, had taken too much insulin, causing the reaction that put him in the hospital for two days. His daughter remains shaken from the experience.

“You’re already concerned about your loved one and you think your dad is about to die, is what I thought,” she said. “And nobody answered. I will probably be in therapy forever over it. It was one of the most traumatic events of my life.”

‘What’s the point of 911 when no one is coming?’

Coleman-Wright, the BSO spokeswoman, said it is imperative that people in need of emergency services not hang up.

The 911 operating system is set up so that each new caller falls to the end of the line instead of getting answered as soon as a call-taker is available. The system also is set up so that abandoned calls are automatically redialed.

Coleman-Wright said an operator was trying to call back as the frustrated callers at the Deerfield house kept dialing about the baby. She said the 911 center tried to reconnect with the callers six times. Dispatchers sent a deputy and an ambulance to the house to determine why so many 911 calls were made.

McNeil was there when they arrived and told them they were too late.

At the hospital, Rudy Dorsey, who rode to the hospital with his brother and Keishawn, said he, like Johnson, was approached by a Broward Sheriff’s deputy asking why no one called 911 and instead drove the baby there.

The question upset Dorsey. “I looked at him in the eyes and asked him, ‘What’s the point of 911 when no one is coming and no one is even answering phones when there is an emergency?’”

He then held out his phone, showing the deputy his call logs to 911: “There was nothing they could say. It was like they saw a ghost or something.”

Unwashed soiled blanket, unworn clothes

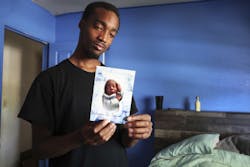

At the Deerfield home where his mother lives, two months after Keishawn died, Johnson stepped into an empty bedroom he used to share with Keishawn, his 2-year-old daughter, 4-year-old stepson, and sometimes Glasco, the children’s mother.

The last time they were all together was Jan. 1. Glasco told the Sheriff’s Office she dropped the children off with Johnson on New Year’s Eve. Records say she returned about 11 a.m. on Jan. 1 and saw their baby sleeping near Johnson.

Both told police they stepped outside, first Johnson and then later Glasco, leaving Keishawn asleep on the bed. At noon, Glasco went to check on the baby, a police report says. That’s when panic started — Keishawn was unresponsive, lying on his belly on the bed.

No evidence exists showing Keishawn with internal or external injuries when he died, a Broward Sheriff’s Office investigative report and an autopsy report say. The same for any congenital abnormalities. Screenings for alcohol and drugs came back negative, according to an autopsy report.

The report listed Keishawn’s cause of death as Sudden Unexpected Infant Death. What led to the death is not known, according to the Medical Examiner’s report.

“I miss him every day. I still cannot believe he’s gone,” Johnson says.

All the children are gone for now. Child Protective Services stepped in, saying Johnson’s daughter and stepson would be better off if Johnson had his own place, or a place where there would be more room for his children to visit and stay, Johnson said.

While the older children left with most of their belongings, in the small bedroom remain the few things Johnson collected for his son since Keishawn was born.

“My mom doesn’t want me to wash this,” he said in March, holding up a small, slightly soiled blanket that his son used. “I’m not washing nothing.”

There are socks for newborns, a hat the baby never had a chance to wear that looks like the head of an owl. There’s also a handful of baby bodysuits. Johnson holds onto the snapsuit that says “National Champion” and brings it closer. A smile splits his face: “I can still smell him.”

Eileen Kelley can be reached at 772-925-9193 or [email protected]. Follow onTwitter @reporterkell. Brittany Wallman can be reached at [email protected] or 954-356-4541. Follow her on Twitter @ Brittany Wallman. Lisa J. Huriash can be reached at [email protected] or 954-572-2008 or Twitter @LisaHuriash. Spencer Norris can be reached at [email protected] or 570-690-3469.

©2022 South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Visit sun-sentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.