Remaining physically fit for duty is a vital job requirement, paid or volunteer firefighter alike. Today’s emergency environment is stressful, complex, dynamic and fast-paced, and the ability to perform strenuous functions is often needed to achieve mission-critical tasks. Many of our critical responses are high-risk/high-consequence events, requiring the firefighter to “get it right” the first time. At some point during your fire service career, you will be challenged to perform strenuous, physically demanding and exhaustive functions, often simultaneously and sequentially during the response.

As firefighters, we combine learned skills, knowledge, attitude, mental fortitude and physical prowess to respond to the needs of our customer. We are not afforded the luxury of do-overs and are always expected to perform optimally. Success is dependent upon the responders being mentally and emotionally engaged and physically capable of performing their task(s). As Kerrigan and Moss underscore in “Firefighter Functional Fitness,” Being physically fit for duty is one of the most vital and fundamental ingredients of being a successful firefighter.1

Four approaches to fitness

Our attitude and belief toward physical fitness is often a determining factor in our desire to remain physically capable of performing our job. If we view fitness through the lens of the fire service culture, we can easily identify four distinct approaches to physical fitness.

1. The Mirror Firefighter: The first approach are those firefighters who look great in their duty uniform, having spent countless hours exercising specific body parts. These are those firefighters who look terrific in front of a mirror but lack cardiorespiratory stamina and muscular endurance to perform under strenuous conditions.

2. The Cardio Nut: Cardio nuts are often found running 3–5 times per week. These members have great endurance, but lack upper-body muscle strength.

3. The Recliners: This group is the most troubling, but unfortunately very common—firefighters who rationalize their lack of activity due to tenure, lack of time and that they won’t be around for the “big-one” anyway. “Why should I work out? I’ve been fine for a long time; nothing will happen to me.” These are the firefighters who practice their favorite training—from a recliner.

4. The Functional Athlete: When we combine the efforts of our “mirror” firefighter with that of our cardio nut, we get much closer to describing the best practice for the firefighter athlete. This is our fourth fitness culture or group. The foundation of fire service fitness is integration. It's about teaching all the muscles to work together rather than isolating them to work independently, doing so in a manner that builds cardio, strength and endurance. Functional athletes use combinations of functional movements (push, pull, lift, bend, carry, craw, etc.) performed in rapid sequence. Our activities of daily living involve functional movement. Whether we are on duty or off, we are required to move—up and down, backward and forward as well as side to side. Functional movements test balance and coordination and involve both upper and lower multi-muscle groups. This style of exercise improves strength and range of motion, while increasing our cardio and muscle endurance.

From a review of all four fitness approaches, it should be clear that the functional athlete is the one we strive to be—and research underscores why.

Health benefits

The importance of firefighter fitness, as it relates to overall health benefits, cannot be overstated. Studies by the U.S. Army have shown that individuals with lower levels of cardiorespiratory endurance or muscular endurance are more likely to be injured and that improving fitness lowers injury risk. In his report on the importance of physical fitness for injury prevention, J.J. Knapik reports that, “those who are more fit perform activity at a lower percentage of their maximal capability and so can perform the task for a longer period, fatigue less rapidly, recover faster, and have greater reserve capacity for subsequent tasks.”2

Not only is the potential of injury reduced when fitness is improved, but also being physically fit minimizes our risk of death due to cardiac and cerebrovascular insult. In 2016, firefighter cardiac-related events accounted for 38 percent of the deaths and 42 percent of the line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) over the past 10 years.

Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) believe that more active and fit individuals tend to develop less coronary heart disease (CHD) than their sedentary counterparts.

Choosing a fitness regimen

A comprehensive wellness approach to fire service injury and LODD reduction begins with programs designed to address physical fitness, nutrition, hydration and rest/recovery. One aspect of this wellness approach, functional fitness, aims to improve performance and reduce the risk of health-related injuries and deaths.

The concept of what “fitness” is relates directly the individual’s knowledge of beneficial exercise, the value placed on fitness and one’s life goals. Fitness to many firefighters ends up being subjective in nature (i.e., we define what “fitness” means to us as individuals). This further confuses our attempts to identify a “best practice” approach to exercise effectiveness.

Our ability to perform critical fireground tasks should start as a guide in determining which fitness regime is best suited for firefighters. Critical fireground tasks—laddering, ventilation, fire attack and others—all require the firefighter to move heavy and awkward objects, under duress, often in contaminated environments. These tasks must occur in a coordinated and concurrent fashion, often in quick succession.

Kerrigan and Moss explain why this matters so much for firefighters: “Firefighting is strenuous and affects every body system, and it taxes these systems in ways that are hard to duplicate in any other profession. To best prepare ourselves for the rigors of emergency response, we must train accordingly. Training functionally not only addresses the core strength, cardiovascular capacity, flexibility and strength needs we have as firefighters, it also adds value in terms of increasing proficiency on the fireground and optimizing performance.”

A fitness HIIT

Michelle Miller, owner of the CrossFit My Town in Hamel, MN, says, “High intensity and varied duration multi-joint movements provide effective training and results commonly seen with CrossFit programming and methodology.”

HIIT involves repeated sets of high-intensity effort followed by varied recovery times. Functional movements, done at high-intensity, challenge balance and coordination while simultaneously improving strength, range of motion and endurance. Preferably, a functional exercise should be a multi-muscle and joint movement, working upper and lower body.

Proper technique and form are essential to safely improve fitness and avoid injury when practicing HIIT programs. In addition, healthy eating habits and post-workout recovery serve as a prescription for improved well-being when combined with physical activity.

HIIT can be easily modified for firefighters of all fitness levels, age and gender and may be performed in many ways, such as rowing, cycling, swimming, elliptical cross-training and in general fitness classes. The benefits of HIIT include improved cardiovascular health and endurance, maintaining proportional body mass, increased strength and flexibility.

A progressive approach

A progressive or a staged approach to build strength and endurance is a recommend starting point to begin any exercise program. Progressive conditioning involves scaling, the altering of weight, movement and intensity to accommodate differing levels of fitness. In effect, this produces the same level of intensity by modifying the exercise from simple to complex to improve fitness in a broad range of individuals. This is a recommended practice by many in the exercise science profession.

One cost-effective and simple starting point to improve fitness is to perform bodyweight functional movements. When done in a group setting, this offers camaraderie, fun and is a safe approach to becoming physically fit. Bodyweight movements—lunges, push-ups, pull-ups, hollow boyd holds, burpees and planks—are beneficial to multiple body parts, and if varied and completed at a fast pace/intensity, effectively improve both cardio and muscle stamina, as well as strength.

Final thoughts

Our goals as firefighters are no different than those of professional athletes. Both are mission focused, want to perform at top efficiency and want to play another day. For the firefighter athlete, we must have the mindset that every day is game day and that we are physically and mentally prepared to respond.

As firefighters we must be functionally fit, meaning our exercise activities match what we do on the fireground. As firefighter athletes, we need to recognize that increasing flexibility, endurance, strength and stamina benefits our performance. Incorporating functionally based HIIT into a general conditioning program optimizes fitness and provides many other health benefits.

References

1. Kerrigan, D. & Moss, J. “Firefighter Functional Fitness: The Essential Guide to Optimal Firefighter Performance and Longevity.” 2016. Firefighter Toolbox.

2. Knapik, JJ. “The importance of physical fitness for injury prevention.” Journal of Special Operations Medicine. 2015. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25770810

First Steps to Fitness: Do’s and Don’ts

- Do consult a physician to seek medial guidance before starting any physical fitness program.

- Do seek a peer to exercise with. Companionship builds relationships, fosters camaraderie and adds a competitive nature to the program, as well as safety.

- Do build your “base fitness level” before beginning a HIIT program. Building fitness through progressively more challenging exercise and “scaling” the activity to the individual are vital to remain injury free and attaining fitness goals.

- Do focus upon finding your own optimal training intensity as opposed to trying to keep-up with others.

- Don’t become discouraged. Becoming the athlete firefighter takes time and is hard work. Be persistent.

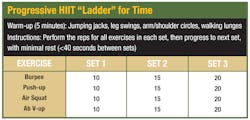

Progressive HIIT "Ladder" for Time

Warm-up: 5 minutes

Jumping jacks, leg swings, arm/shoulder circles, run in place

Perform all repetitions (reps) in each set, progress to next set in sequence, with minimal rest (>40 seconds) between sets

About the Author

Richard Kline

RICHARD C. KLINE is a 40-year fire service veteran who recently retired from the Plymouth, MN, Fire Department, following 23 years of service as fire chief. He is a frequent regional and national speaker who covers topics that relate to command competencies and firefighter safety and health. Kline can be contacted at [email protected].